Lifting the Emotional Embargo With Cuba

The June heat was so intense, the air so still, that the open balcony doors offered little relief. Anthropologist Ruth Behar felt her clothes sticking as she looked over the 30 or 40 people who filled every seat on the second floor of the Pharmaceutical Museum in Matanzas, Cuba. Some were adults, literature fans from this provincial capital east of Havana. Others were middle-grade students, inching toward adolescence yet well-behaved, wearing beige and brown school uniforms that represented their country’s egalitarian ideal.

From the balcony of the museum building—a 19th-century French-Cuban pharmacy filled with herbs, ceramic and glass vessels, and old prescription books—Behar could see Parque de la Libertad, with its statue of the revolutionary poet José Martí towering above a liberty figure with her shackles broken. Inside, another celebration of poetry was taking place. Behar’s friend Rolando Estévez Jordán, an internationally exhibited book artist who lives in Matanzas, was giving a dramatic reading of “Eternity,” a poem about impermanence by the aristocratic Cuban patriot Dulce María Loynaz. “I’ve songbirds in my garden,” Estévez proclaimed in Spanish, “Chanting crystal songs / I won’t give you them, for they / have wings to fly away.” Many, including Behar, wept at Estévez’s theatrical delivery. “For you, infinity,” he continued, “or nothing.”

Estévez then asked Behar, a MacArthur Fellow and a professor at the University of Michigan, to introduce the next reader. She looked at her friend and collaborator Richard Blanco, who had flown with her from Miami several days earlier. “He’s a very, very important poet who writes about growing up in Miami and hearing about Cuba from his family and the exile community,” she explained in Spanish to an audience largely unfamiliar with Blanco’s work. “And Richard has now attained something extremely important. He was asked to write and to read a special poem for the second inauguration of President Obama.”

Blanco, a handsome man of 48 with spiky salt-and-pepper hair, read a poem about his mother’s departure from Cuba in 1967: “Taking only what she needs / most: hand-colored photographs of her family, / her wedding veil, the doorknob of her house.” Blanco’s initial nervousness subsided as he noted the subtle nods and looks of recognition from those who had parted with their own siblings and cousins.

As Behar listened, and later as she read from her own poetry and from her forthcoming novel Lucky Broken Girl, her heart pounded, not from nerves but from hope. She was spending the afternoon with two good friends who live in countries that have historically been at odds—countries that form the halves of her own identity—and the relationship between their governments was starting to relax. There was no microphone in the room, but Behar didn’t need one to read. Her lungs felt full of air, her body loose. “Totally present,” she recalls of the moment. “Just being there.”

Traveling with an old friend, and giving public performances, was a departure from Behar’s usual work in Cuba. Since the early 1990s, the professor has visited at least 50 times, generally alone, to study the island’s small Jewish community. But 2015 was shaping up as an extraordinary year in the history of U.S.-Cuba relations, and to her it demanded an unorthodox anthropology.

Six months earlier, in December 2014, President Barack Obama had announced the impending resumption of diplomatic relations with Cuba. The United States would re-establish an embassy in Havana, and it would loosen travel and banking restrictions, make it easier to import and export goods, and cooperate with Cuba on shared concerns like environmental protection and ending human trafficking. According to news reports, the policy followed secret negotiations and a prisoner swap brokered in part by Pope Francis.

“I have come here to bury the last remnant of the Cold War in the Americas,” Obama would later say during a March 2016 visit to Cuba, the first by a U.S. president since Calvin Coolidge in 1928.

In response to the 2014 announcement, Behar and Blanco started imagining a reconciliation project that would incorporate both ethnography (the study of cultures) and poetry. Blanco, in conversations and public statements, had referred to an “emotional embargo,” born of ideological discord, that separates Cuba’s residents from their relatives abroad. “We haven’t really talked,” the poet explains. “We’ve been fighting, and we politicize things”—and in the process, he says, we have failed to address some of the more personal implications of being cut off from a homeland and from loved ones. “One is the reality that we’re never going back, not back to anything remotely similar to what we left behind. And that’s painful. It gets funneled as a political thing, but in reality it’s just plain old pain and loss.”

Maybe, the two friends reasoned, combining their disciplines of anthropology and poetry could help reconnect countries that were estranged after Fidel Castro took power in 1959 and the United States imposed a commercial embargo. “We need to come to terms with all these years of broken relations,” says Behar, “and the effect it has had on us as a people.”

“Bridges to/from Cuba,” as they named the project, would be published in the form of a curated blog, in Spanish and English, available online and also emailed as a bulletin to Cuban residents with limited Internet access. The format, Behar hoped, would allow for both deep reflection and timely responses to current events. Behar and Blanco began recruiting voices from Cuba and its diaspora (émigré communities off the island) and from other Latin American countries: stories written in what the duo calls “an emotional register that breaks the heart and tries to heal it too.” They also made plans to interview everyday Cubans—bringing in what Behar calls “more of an ethnographic dimension”—and to publish brief reports on new efforts to unite Cubans across a geographical divide.

Behar and Blanco know intimately what it means to grow up in a divided world. When Behar started visiting Cuba for her research, her family couldn’t understand what drew her back to an island where emigrants were once called gusanos (worms) and strip-searched in the airport. “Don’t talk about politics; you could end up in jail,” relatives warned her. For Blanco, growing up in Miami’s immigrant community meant that Cuba was an imagined place of photos and letters. “And America felt like a place I hadn’t gotten to quite yet,” he says, “a place I saw on television shows like The Brady Bunch.”

Now was a chance to bring these worlds together. For Behar, that meant venturing into a liminal zone where scholarship and the arts meet. Working in these borderlands is not how most anthropologists operate, but it’s not unprecedented: A few years ago, New York University’s Renato Rosaldo coined the Spanish term antropoesía to describe “verse with an ethnographic sensibility.” Borders like these fascinate Behar, who has been aware of straddling them all her life: being Cuban and American, Latina and Jewish, researcher and poet, observer and feeler, one who studies others and one who flips the lens back on herself.

Straddling boundary lines, and being open to the emotions that it brings, is not an effortless act. “Sometimes it can be wrenching to go back and forth between Cuba and the U.S,” Behar says—“this sense of: Where do I really belong? Can I belong in two places?”

Behar is 59. She has shoulder-length brown hair and dark eyes that dwell at the intersection of conviction and tenderness. Born in Havana, she grew up in two separate Cuban-Jewish traditions. Her mother’s relatives were from the Ashkenazic, or Central and Eastern European, branch of Judaism: They spoke Yiddish, ate gefilte fish, and prided themselves on logic and modernity. Her father’s family was from the Sephardic branch, which generally traces its roots to Spain. They had immigrated to Cuba from Turkey and spoke the Judeo-Spanish language Ladino, which made for an easy transition to Cuban Spanish. They ate stuffed grape leaves and told stories of hardship with dramatic flair. Both communities arrived on the island starting in the 1920s but lived and worshipped so separately that her parents’ union was almost considered an intermarriage. “I was told that my temperament—a strong will, a fierce rage that came from a source I couldn’t begin to fathom, and an inability to forgive those who’d wronged me—was a Sephardi temperament,” she wrote in her 2013 memoir Traveling Heavy.

Behar’s family left Cuba after the revolution, when Castro’s government confiscated the lace store owned by her maternal grandparents. They eventually landed in New York City, where Behar spent most of her youth. More adept at English than her Spanish-speaking parents, she interpreted the mail that arrived at their Queens home and helped them order meals during rare visits to American restaurants. “There was that experience early on that I was a translator, that I was between cultures,” she says. “I was awash in all these languages, and people who had different claims to different places. I didn’t have the word diaspora in my vocabulary then, but in some ways I was living diaspora.”

She was a studious and often-solitary girl in a gregarious family that loved to joke, dance, and play dominoes. Their upstairs apartment was noisy—between the television’s blare, the clang of her mother’s pots and pans, and her brother’s rock-and-roll. Her desire for an advanced liberal arts education received “no support at home,” she says. “I had a lot of struggles with my father, who has a very traditional idea of how women should be: finish high school, then wait till a man comes and marries you.”

Read more from the archives: “Remembering the Woman Who Was My Second Mother in Cuba.”

Seeking both literal quiet and relief from her adolescent turmoil, Behar would sit at the bottom of the stairwell, near the front door, and read. “Poetry offered a refuge,” she says, “a way to be with myself.” She read Emily Dickinson, and she wrote, too: “terrible high-school poems” about not being understood. Her father disapproved of this bookishness. “You’re turning my house into a funeral home,” she remembers him saying.

Behar studied literature at Wesleyan University, but almost every time she tried to enroll in a creative writing class, she found it full. She also felt frustrated that many of her humanities professors focused so tightly on the West. An undergraduate class with Johannes Fabian, a cultural anthropologist who had done fieldwork in Central Africa, offered her a new way to view cultures beyond her own. “I remember distinctly learning about Bantu philosophy,” she says, “and going, ‘Oh, wow. Why was I only hearing about Hegel?’” After graduating, she switched directions and entered the doctoral program in cultural anthropology at Princeton University.

She plunged into the world of academic writing, which didn’t quite suit her either. “It was taxing to read all the theory and all of those classic ethnographies,” Behar says. “I thought: Why are they writing in this stifling way?” But there was no time to write poetry, and she set it aside as she earned her doctorate and began her fieldwork in Spain and Mexico.

In the early 1990s, as Cuba became more open to visitors after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Behar turned her research eye on her birth country. She was academically curious but also wanted to connect with the place that had so profoundly shaped her family’s story.

Those first trips were particularly emotional. “I would be walking around Havana and having the most horrible panic attacks,” she says. “What if Fidel Castro died while I was there? Would a riot break out? Would I never be able to leave again?” At times she thought she’d faint, literally, from anxiety. Yet she was mesmerized too: by the dialect, the humor, the familiarity of the people she met.

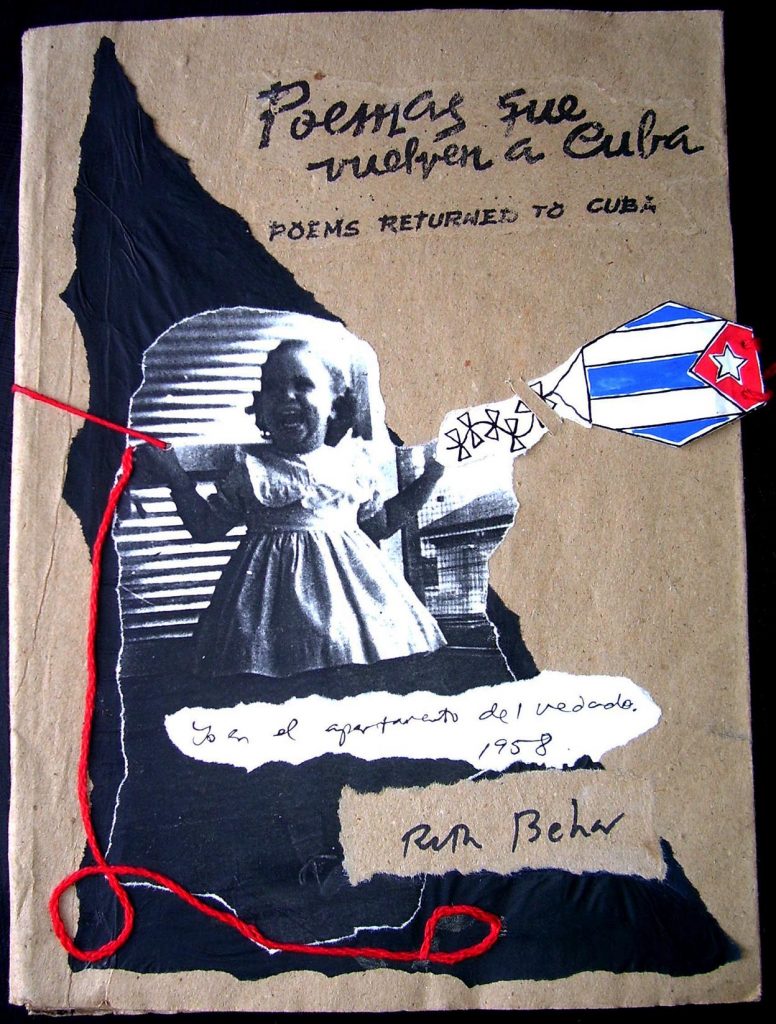

The panic subsided as Behar built new relationships and reconnected with people who knew her as a child in Havana, including her former nanny. Among those she met was Estévez, whose handmade books combine illustration with text. Inspired by his art, she returned to writing the verse she had abandoned in graduate school. Estévez helped Behar with the literary nuances of Spanish, and he published four bilingual books featuring her poems.

Meanwhile, Behar learned about other poet-anthropologists. Among them were Edward Sapir and Ruth Benedict, who in the 1920s read and critiqued each other’s poetry in what their colleague Margaret Mead—known for her pioneering work on how culture influences human development—called a “vivid, voluminous correspondence.” In one poem, Sapir told the story of one of his informants, Tom (Sayach’apis), a blind Nootka tribesman in western Canada: “I have four names. The first is ‘Stand-up high.’… / Long years ago there came down from the sky / The Heaven-Chief and stepped into the dream / My ancestor was dreaming.”

Rosaldo, the NYU anthropologist, says that what distinguishes antropoesía is that “description is central” and that feeling is evoked by the accumulation of details. “Like an ethnographer, the antropoeta looks and looks, listens and listens,” he wrote in an essay that accompanied his 2013 book The Day of Shelly’s Death, which chronicles the 1981 accident that claimed his wife and colleague Michelle Zimbalist Rosaldo. “This form of inquiry resembles field research in that it involves observation, asking questions, attending with patience and care, knowing that meaning may be there, waiting to be found, even if the observer-poet does not yet know what it is.”

Antropoesía is still not considered mainstream, but it has seen widening acceptance, with the Society for Humanistic Anthropology (a section of the American Anthropological Association) sponsoring poetry workshops and competitions. This movement inspired Behar to look for other alternative storytelling vehicles: In 1995 she edited a multigenre anthology called Bridges to Cuba/Puentes a Cuba, and in 2002 she produced a lyrical documentary film, Adio Kerida (which means Goodbye Dear Love), about her personal connection with Cuba’s Jewish community. But she has also continued to produce traditional scholarship: “Being aware of my minority status, I’ve always been a little bit dutiful.”

When Obama made his 2014 announcement about the resumption of diplomatic ties, “we were shell-shocked,” says Blanco. “We were getting all these requests to speak. We didn’t know how to speak, what to speak about.”

Two months later, he and Behar stood in a Miami parking lot after a dinner party. They had developed a close friendship over 20 years of collaboration—teaching together at the Macondo Writers’ Workshop in San Antonio, for example—and Behar had sometimes stayed with Blanco and his partner Mark Neveu during visits to Miami. “And we said: We have to do something,” she recalls. “There are all of these Americans now rushing off to Cuba. There’s all this reporting going on, and a lot of it is so stereotyping, or so inaccurate, or so exoticizing, so romanticizing. What’s going to happen to the stories that we know?” They considered another published anthology but decided instead that a blog would allow for more time sensitivity. “We had a feeling that things were going to change extremely quickly,” she says, “and we wanted to be part of the big conversations taking place.” They also wanted to travel together, to see Cuba from each other’s vantage point. (Blanco had previously only visited there to see relatives.)

It seemed natural that creative writing, including poetry, would be part of the mix. “Art is about the study of human nature, which parallels a lot of what anthropology is about,” Blanco says. “The bridge is made of many materials.” Among the first year’s blog posts are an account by Liz Balmaseda—a Cuban-born journalist in Palm Beach Gardens, Florida—about the death of her gay cousin and a trip to Havana to bury his ashes, and a meditation on homecoming by poet and playwright Carlos Pintado, who immigrated to the United States in 1997.

And it has included writing by both founders. Behar and Blanco set the tone for their June 2015 trip by weaving their individual work into a single extended poem. Blanco wondered if he’d find clarity about his relationship with Cuba if he could “return / just once more, walk the sugarcane fields / my father once cut, drive down the road / where my mother once peddled guavas / to pay for textbooks.” Behar responded with a promise: “We’ll lower our ears to the red earth of our island. Listen if she still calls for us.”

Behar and Blanco are now lining up future contributors and planning to scour Cuba for young writers who are unknown in the United States. They also plan to tell stories in other formats, from photo essays to surveys.

By collaborating with artists and writers she considers “coequals,” Behar hopes to erase the traditional power imbalance between an anthropologist and the people she studies. “You’re building together a sense of place,” she says. “It’s not the model of the lone ethnographer, but rather it’s a shared process—a quilt of different perspectives on what it means to be Cuban and what is Cuba. I think of it as a shared ethnography.”