Below you will find teaching units across anthropology that are crafted for introductory courses. These units offer an opportunity to use SAPIENS content in the classroom, alongside additional resources, to enrich the teaching and learning experience. Feel free to incorporate those that interest you into your syllabus or teaching schedule.

Each unit is comprised of a brief summary of the subject matter, related SAPIENS articles, keywords, talking points for professors, academic articles, student discussion questions, and more. Hyperlinks lead you to such online resources as the main SAPIENS articles for each unit, keyword searches that can help you find related magazine content, and select activities and additional resources.

You can access a piece that details more about the history and goals of Teaching SAPIENS here.

Biological Anthropology

-

1Hominins

Hominins, of which only one species—Homo sapiens—currently exists, are members of the family Hominidae. In this unit, students will learn about extinct hominin species and gain a general understanding of what anthropologists have been able to discern about our ancestors and other hominin species.

-

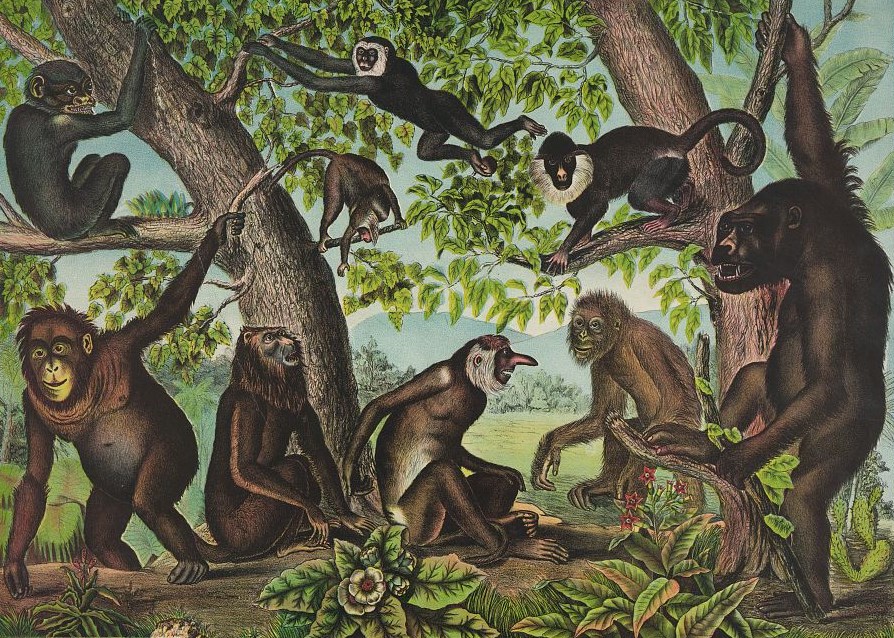

2Nonhuman Primate Diversity

As members of the Primate order, modern humans share more genetic material with monkeys, lemurs, and apes than with other mammals. In this unit, students will learn about the diversity among nonhuman primates and what research has revealed about primate behavior, communication, and other social interactions.

-

3Early Homo Sapiens

Biological anthropologists place the initial emergence of our species, Homo sapiens, around 300,000 years ago. In this unit, students will learn about the evolution of our species and read about some of the many questions biological anthropologists are still asking about our ancestors.

-

4Human Genetic Variation

Scientific explanations for and appreciations of human genetic variation often remain at odds with social views on human diversity. In this unit, students will learn how biological anthropologists address genetic variation. They also can consider anthropologists’ ongoing struggle to address the discipline’s historical role in perpetuating scientific racism.

-

5Human Behavior

Biological anthropologists are interested in human behavior and what role evolution, genetics, and biology play in determining why we act the way we do. In this unit, students will learn about some of the current discussions regarding aspects of human behavior and what current events may indicate about our ability to adapt to unforeseen circumstances.

Archaeology

-

1Archaeological Methods

Archaeologists make use of a wide array of methods and methodologies in order to conduct accurate research that yields credible results. In this unit, students will learn about some of the different methods that archaeologists are incorporating into their work and innovative techniques that are helpful for exploring the past in new ways.

-

2Ethics in Archaeology

Archaeological discussions about ethics are reshaping the discipline both in theory and in practice. This unit provides a general introduction to some major ethical principles and presents examples of ethics in action and ongoing challenges.

-

3Museums

Museums are dynamic spaces undergoing major shifts in policy and ethics, since, historically, they have been sites of contention for many reasons. In this unit, students will gain insight into changes in museum policies on housing controversial art and culturally significant items.

-

4Archaeology and Colonialism

Colonial perspectives about hierarchies of human worth and worldviews shaped the creation of anthropology, and modern archaeologists are grappling with this legacy. This unit encourages students to explore the impacts of colonialism on the discipline and consider how archaeologists are taking steps to decolonize their methods and theories.

-

5Public Archaeology

Archaeology as a discipline has much to offer the world outside of academia. In this unit, students will learn about how archaeologists bring their work to the public and how professional archaeologists use their training to make an impact on society through alternative career paths.

-

6Black Archaeologies

In this unit, students will learn about the methodological and theoretical approaches Black archaeologists and archaeologists conducting work in partnership with Black communities are incorporating into their work. They will also learn about the critiques scholars are making about the discipline from the standpoint of Black archaeologies and explore how archaeologists are undertaking projects that ask new questions about history to offer important insights into the past and present.

-

7Indigenous Archaeologies

In this unit, students will learn about archaeology being conducted by, for, and with Indigenous peoples. They will read about ethical practices and viewpoints in Indigenous archaeologies that are reshaping the possibilities for collaborative work and the potential for archaeological projects to be driven by the needs of the communities it impacts.

Linguistic Anthropology

-

1Language and Identity

Language shapes the way we think about, understand, and communicate who we are individually and as members of the many intersecting groups that define us. This unit will allow students to consider how identity is demarcated and sustained by language and ways of speaking both among members of the same group and between different populations.

-

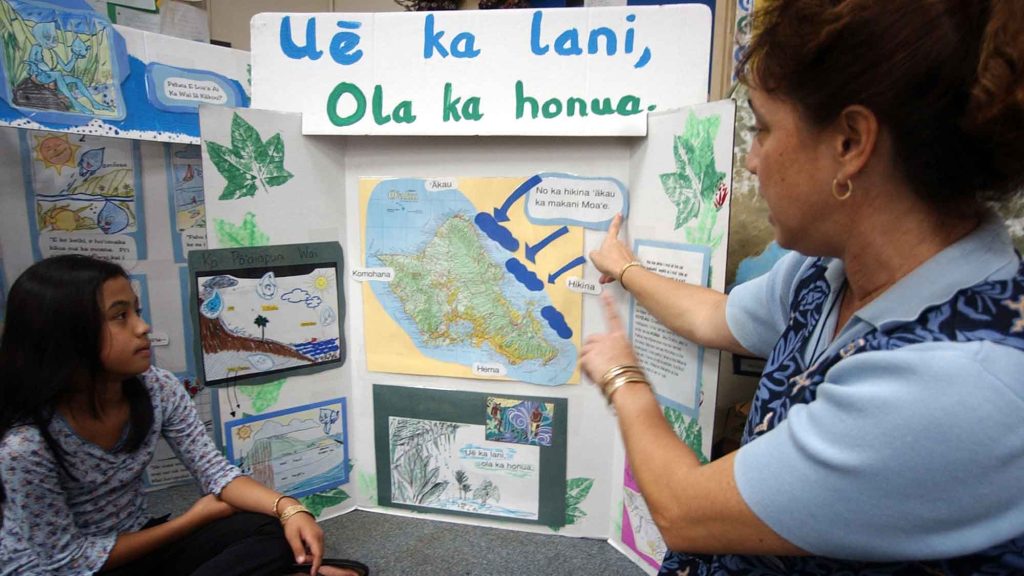

2Language and Diversity

Linguistic anthropology lays plain the dynamic nature of languages and how they make possible a variety of different understandings of the world around us. In this unit, students will consider language creation and extinction, and explore a diversity of languages and the various ways researchers study languages.

-

3Language and Gender

Words, phrases, and context tell us a great deal about how we think, speak about, and ultimately view people of different genders. This unit encourages students to think about the way language lays bare the gender inequality that is present in our societies and how changes to language are part of creating more equitable systems.

-

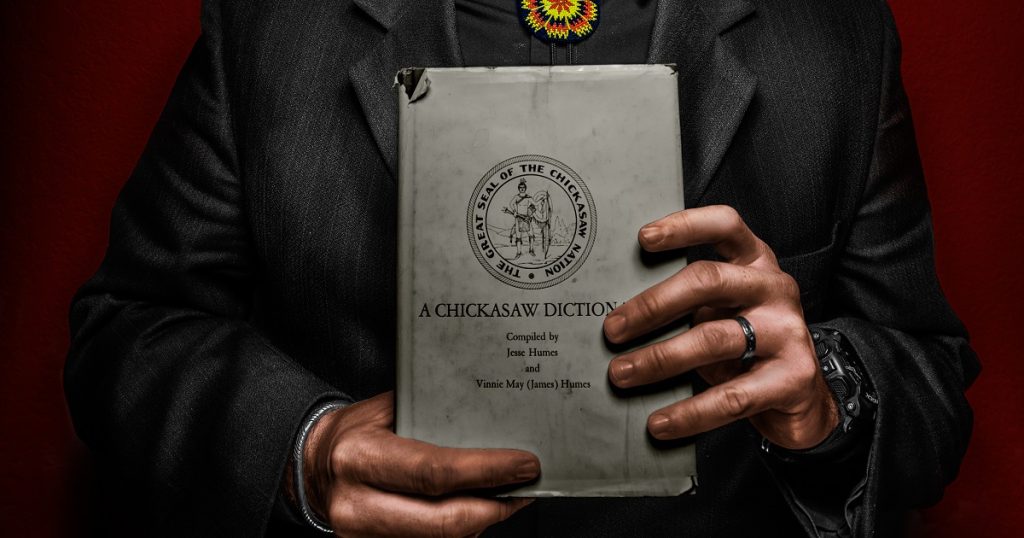

4Language and Colonialism

Colonization has had a tremendous impact on Indigenous languages. In many cases, it has resulted in a decrease in the numbers of native language speakers, and, in some instances, language extinction. This unit will help students understand why and how colonial efforts targeted language in attempts to eradicate Indigenous cultures. Students will also learn about efforts to reinstate endangered languages and the effects of colonization on language politics today.

-

5Language and Power

Institutionalized power determines the way we speak and guides the conversations that we have. Through language, power makes itself known via state messaging and sets the tone for social interactions with the use of predetermined wording and phrases. In this unit, students will study examples of how state power is exerted through speech and written language. They will have a chance to consider how the media, police, and military forces use language to maintain their control over large populations.

-

6Language and Race

Around the world, language functions as much more than a technical means of communication. Conversing with others in a specific language with certain rhythms, styles, registers, forms, and dialects can prompt different modes—sometimes, even categories—of citizenship, connection, and belonging. In this unit, students will learn about language as it relates not only to race relations and constructions of racial identities but also to the maintenance of or challenge to wider discriminatory systems. Through examples from across time and space, students will also gain an understanding of how languages thrive, clash, broaden, or limit people’s access to different groups and spaces.

Cultural Anthropology

-

1Power and Hierarchies

Power and the structures that determine how power is generated, retained, and wielded have been described and critiqued though anthropological studies. This unit provides students with the opportunity to take note of the power structures that shape the world. They are encouraged to consider the nature of power, the way it is exerted, and the implications for those who have state and structural power and those who seek to obtain it. Finally, they will learn about individual and collective efforts to challenge and dismantle these structures, and develop new systems.

-

2Gender and Sex

Gender and sex shape our personal identities, indicate how we should relate to others, and help us determine where we fit into our worlds. This unit gives students an opportunity to consider the differences between sex and gender cross-culturally. They are encouraged to question power imbalances along gender lines and how institutions are changing to reflect debates around gender and sex.

-

3Religion

Anthropological studies of religion consistently demonstrate the dynamic and ever-changing nature of organized belief systems. These systems are constantly in flux, as are ways of understanding and categorizing them. In this unit, students will consider religion in specific sociocultural contexts. They are encouraged to consider the influence of politics, economics, cultural change, and history in shaping religion and the religious practices they will read about.

-

4Food

Food is vital for our survival as human beings, but it also plays a major role in how people determine where they fit in their society, remember their collective histories, and shape their lives. In this unit, students are encouraged to consider the implications of anthropological findings on how culture determines what people consider food and how politics shapes what people consume and how we do so.

-

5Medical Anthropology

Medical anthropology considers culture’s presence and role in medicine and ways of thinking about the body, well-being, illness, and healing. Medical anthropological approaches center biology and the sociocultural mechanisms that help different groups make sense of illness, health, bodily functions, and well-being. Students will learn how medical anthropology can help make sense of cultural perspectives of medical issues, and why the field is so well-positioned to bring about meaningful improvements in health care systems and communities.

-

6Symbolism

Symbolism is an important aspect of human communication and consists of finding ways to reduce complex thoughts to effective signs or images. This unit encourages students to think about the myriad ways that humans create symbols to communicate with one another and how those shared meanings are negotiated.

-

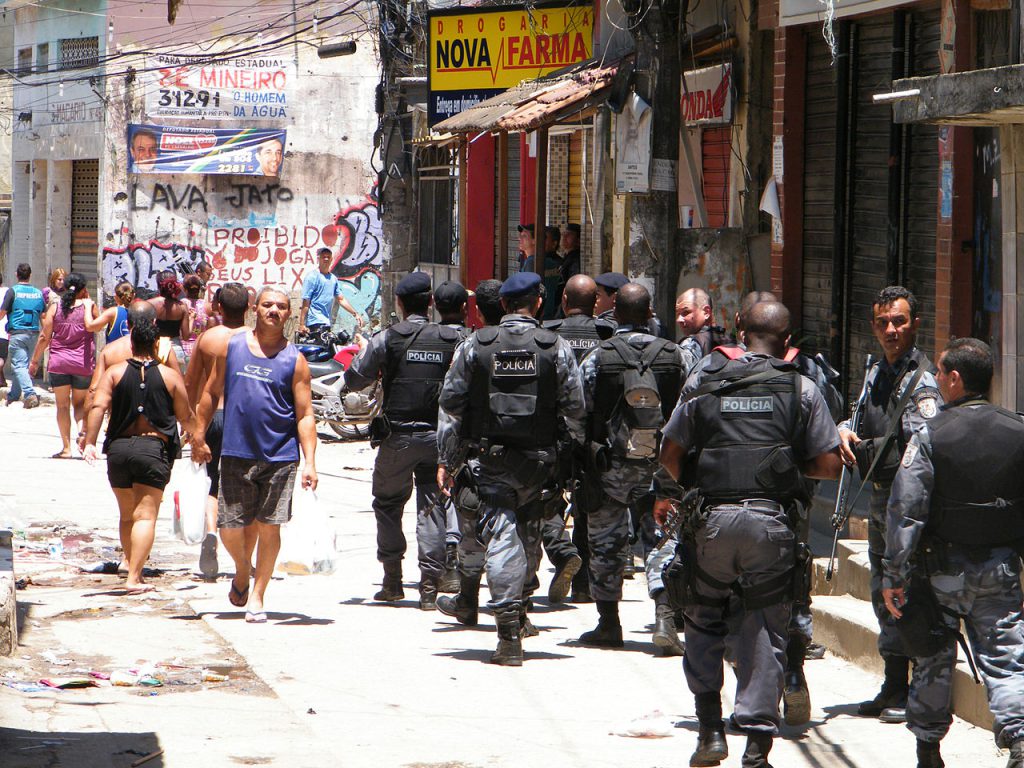

7Policing

Governments task police forces and other security units with the responsibility of maintaining order and control over civilian populations. In this unit, students will learn about policing in different countries around the world and observe the differences and similarities in law enforcements’ approaches and methods. They will also gain an understanding of how policing affects different communities and become familiar with how power, violence, and control are embodied and meted out by the institution and by individual officers. Students will study critiques of policing put forth by various scholars.

-

8Pandemics

2020 will be remembered as the year of the COVID-19 pandemic, but humanity has withstood many other pandemics over millennia. In this unit, students will learn how previous pandemics have affected human cultures, what anthropologists who study pandemics can tell us about underlying problems in our societies, and what we need to know moving forward.

General Anthropology

-

1Professional Anthropology

In this unit, students will learn about the ways trained anthropologists use their skillsets outside of an academic setting. They will read about and discuss different career paths, how anthropologists are bridging work in higher educational institutions with projects beyond traditional settings, and how anthropological training can support work in other industries and careers. Finally, students will be able to take stock of their own skills as anthropologists in training and consider how they might apply them in the future.

-

2Anthropological Poetry

In this unit, students will learn how anthropological poetry deftly draws readers into a moment, image, sensation, metaphor, or inquiry—less so into an argument, proof, or explanation. As a creative expression, this subgenre of poetry allows for an embodied multiplicity of insights and emotions shared by skilled participant-observers or researchers. Students will explore how anthropologists turn toward poetry to process, reflect on, and share their fieldwork, personal/communal experiences and emotions, and/or research.

-

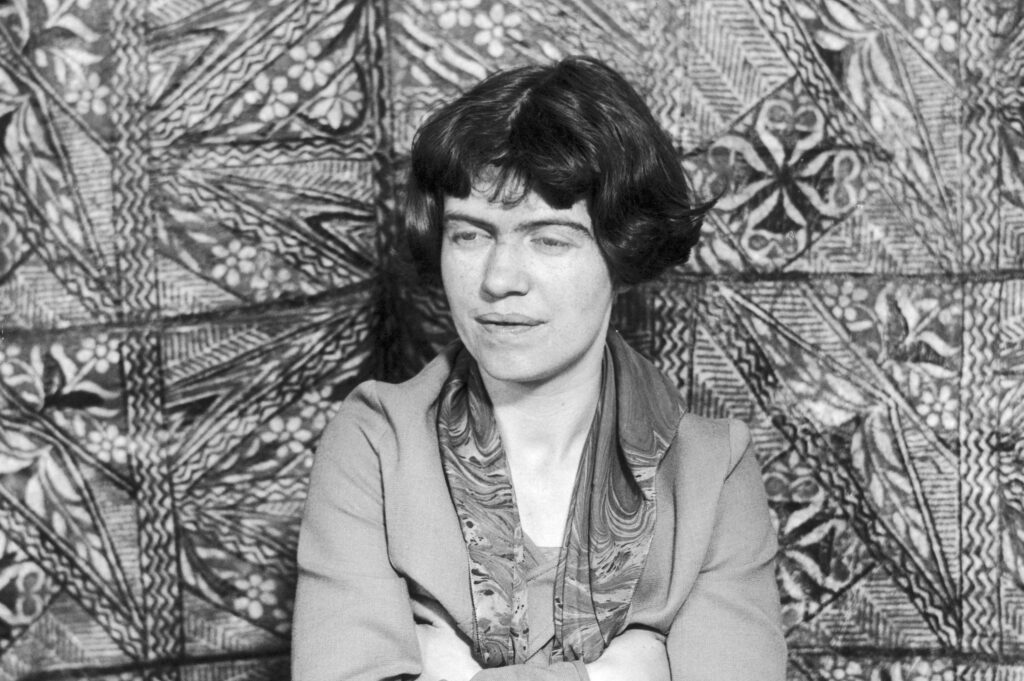

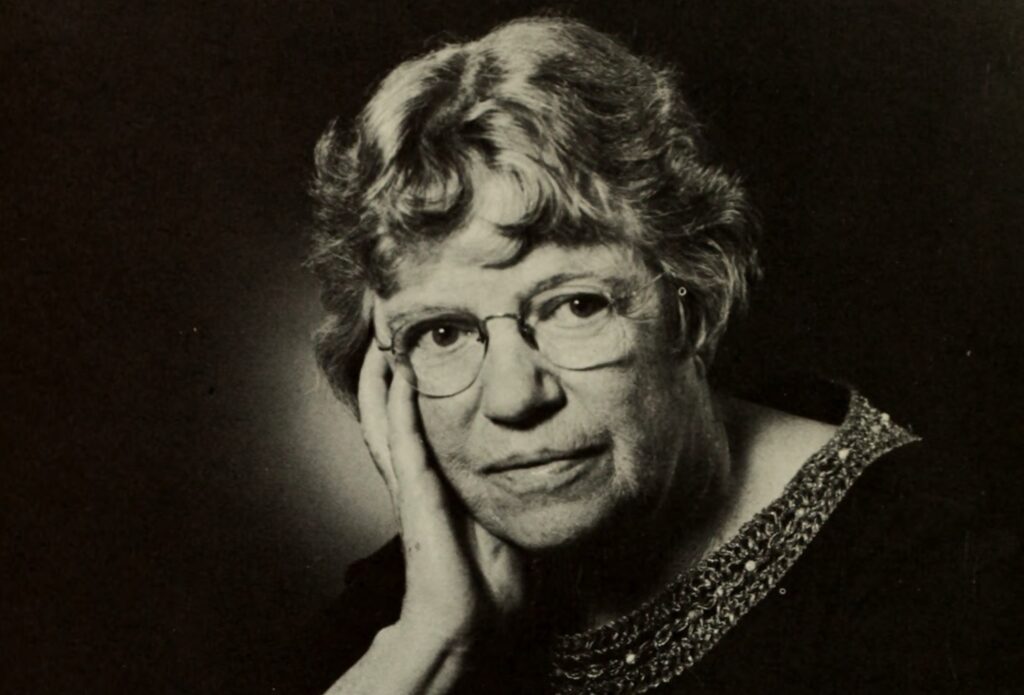

1Margaret Mead in American Samoa

In this unit (to accompany SAPIENS podcast S6E1), students will be introduced to anthropology, focusing on the field in the early 20th century. Students will examine Margaret Mead as a historical figure, her work in American Samoa, and her impact on anthropology.

-

2Adolescence as a Social Category

In this unit (to accompany SAPIENS podcast S6E1), students will examine the idea of adolescence as a focus of anthropological research and investigate the creation of the social category of adolescence. Students will explore Margaret Mead’s ideas and contentions about adolescence that resulted from her work in American Samoa.

-

3Margaret Mead’s Ethnographic Work in Samoa

In this unit (to accompany SAPIENS podcast S6E2), students will learn, through Margaret Mead’s fieldwork in American Samoa, the facets of ethnography and the impact of her work. By exploring and discussing Mead’s findings, students will be able to analyze the bigger picture of her influence through an anthropological lens.

-

4Margaret Mead’s Remarkable Career

In this unit (to accompany SAPIENS podcast S6E2), students will learn about Margaret Mead’s career, including how her accomplishments and feminist perspective impacted future anthropologists and how her findings influenced 20th-century America. Students will read about significant milestones in her career and learn how her academic journey led toward her research outcomes with the Samoans and other anthropological achievements.

-

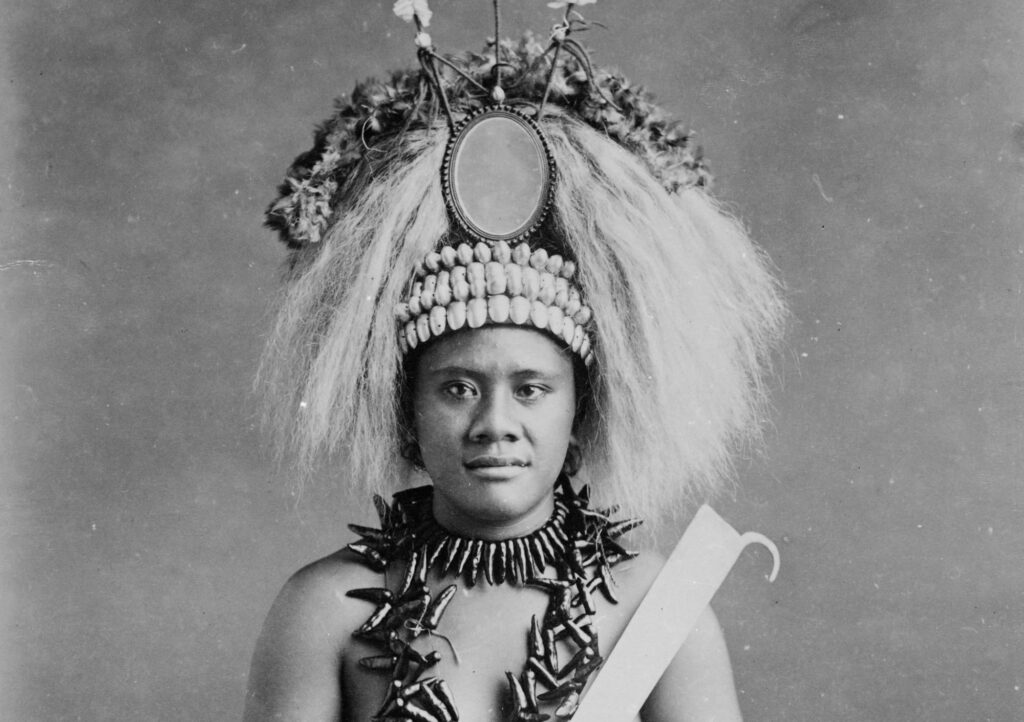

5Samoan Voices

In this unit (to accompany SAPIENS podcast S6E3), students will compare the different responses of Samoans to Margaret Mead’s work and her publications on American Samoa. Using Mead as a guide, students will examine how “outsider” anthropologists study cultures different from their own and the significance this has on global views of those societies. Students will examine how Samoans, being the “insiders” in their culture, viewed Mead’s outsider perspective and the conclusions she drew. This concept of outsider and insider will be further examined to explain how conclusions made by Western outsiders shaped the global view of non-Western cultures.

-

6Positioning the Anthropologist

In this unit (to accompany SAPIENS podcast S6E3), students will track the changes in anthropological scholarship by looking at the discipline before and after Margaret Mead’s groundbreaking publication, Coming of Age in Samoa. Students will plot the major theories in anthropology in the 19th and 20th centuries and will evaluate its progression to be more inclusive and to consider positionality, self-reflexivity, and multivocality.

-

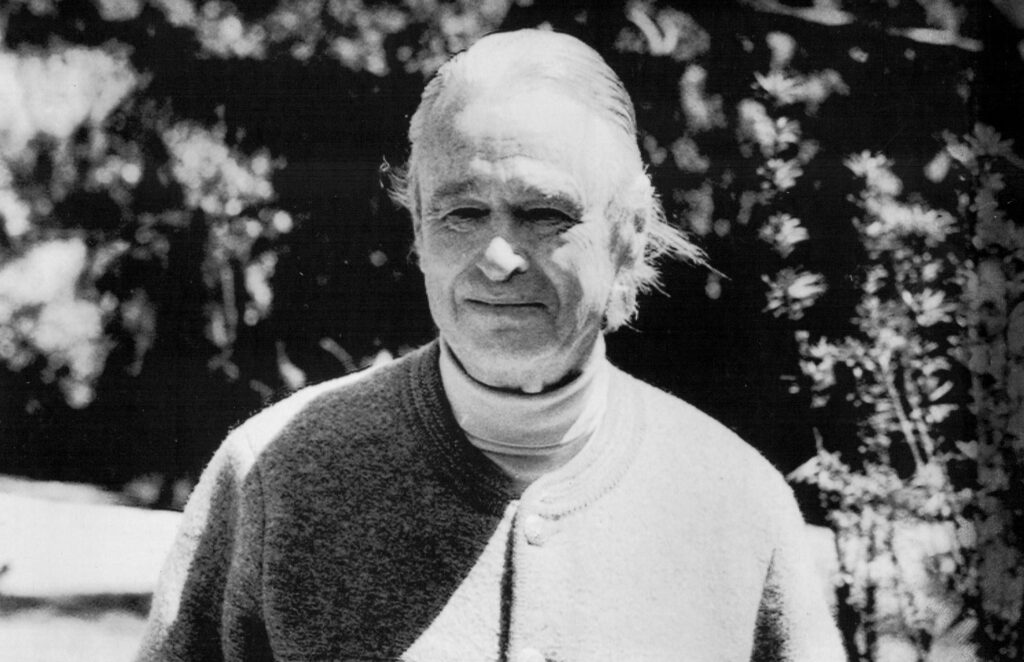

7Mead Versus Freeman

In this unit (to accompany SAPIENS podcast S6E4), students will learn the counterarguments to Margaret Mead’s 1920s American Samoan research from her harshest critic, Derek Freeman. Students will examine Freeman’s experiences and how he presented his research and conclusions. Students will discuss whether his arguments hold weight and what lessons scholars can learn from the Mead–Freeman controversy.

-

8Nature Versus Nurture

In this unit (to accompany SAPIENS podcast S6E4), students will learn the origin of the nature versus nurture debate within the field of anthropology and explore where the debate currently stands. Students will examine the ways in which nature and nurture intersect and explore how the lens of nature versus nurture shaped Derek Freeman’s and Margaret Mead’s understanding of the Samoan people.

-

9Colonialism and Christianity in the South Pacific

In this unit (to accompany SAPIENS podcast S6E5), students will learn about colonialism in the South Pacific and Samoa. Students will explore the history of colonialism and examine how both it and the influence of Christianity affected Samoan people and shaped their views toward the anthropologists Margaret Mead and Derek Freeman.

-

10Legacies of Colonialism in Samoa

In this unit (to accompany SAPIENS podcast S6E5), students will examine the legacies of the colonial era and how Samoans have striven to overcome them. Students will explore how ideologies shape language and the West’s view on Samoa and its people.

-

11Unpacking the Mead–Freeman Controversy

In this unit (to accompany SAPIENS podcast S6E6), students will revisit the Mead–Freeman controversy in depth, reassess how Derek Freeman critiqued Margaret Mead, and then study the consequences of the dispute within the field of anthropology. Students will apply lessons from the controversy to current research and theories.

-

12The Influence of Freeman and Mead

In this unit (to accompany SAPIENS podcast S6E6), students go beyond the Mead–Freeman controversy to explore the repercussions of nature versus nurture in U.S. scholarly debates from the 1980s to the 2000s. Students will research how these debates trickled into mass media reporting and affected U.S. society.

-

13The Anthropology of Sexuality

In this unit (to accompany SAPIENS podcast S6E7), students will explore sexuality through the lens of anthropology and investigate the influences of cultural, social, and historical factors on human sexual behavior and identity. Students will use an anthropological framework to examine the challenges of studying sexuality, including researching in diverse cultural settings.

-

14Reading Sia Figiel

In this unit (to accompany SAPIENS podcast S6E7), students will learn about the significance of Sia Figiel and consider how her writings empower marginalized voices and seek to help girls reclaim their lives. Students will compare the significant themes in Figiel’s works, including gender, power, and culture.

-

15Intercultural Understanding

In this unit (to accompany SAPIENS podcast S6E8), students will learn about the importance of intercultural understanding. Culture impacts people’s speech, actions, and thoughts, and students will evaluate how understanding this is the first step to gaining intercultural competence. Students will explore challenges to intercultural understanding and learn how empathy, active listening, and dialogue all play a role.

-

16Using Ethnographic Methods

In this unit (to accompany SAPIENS podcast S6E8), students will learn that ethnography is a research process that involves fieldwork and studying the cultural practices of a group of people in situ. According to Bronislaw Malinowski, the final goal of ethnography is “to grasp the native’s point of view, his relation to life, to realize his vision of his world” (Argonauts of the Western Pacific 1922). In this unit, students will explore fundamental ethnographic principles and look at the nature of culture as it relates to social, economic, and historical factors.

-

17Looking Back at Coming of Age

In this unit (to accompany SAPIENS podcast S6), students will reflect on all topics covered in past units. Students will use the information gathered and put it within a framework of considerations, including the challenges, possibilities, and responsibilities of studying other cultures and societies.