The Viral Atrocities Posted by Israeli Soldiers

Content Warning: The materials below include images of violence.

In early January, a TikTok account affiliated with Israel’s ultra-Orthodox Shas party posted a video that an Israeli soldier filmed in Gaza. Somewhere in the northern part of the Strip, the soldier stands inside a bedroom in a Palestinian home. He has just finished wrapping himself in tefillin—straps with small leather boxes containing Torah scrolls that Orthodox Jewish men usually wear during morning prayers.

Over a soundtrack of pulsing dance beats, the grinning soldier exclaims in Hebrew: “I can’t believe that I am saying this. I am putting on teffilin in a house in Gaza. A house in Gaza!”

The 22-second reel offers viewers a short tour of a home left in a hurry. Handbags are shoved into a closet, clothes litter the floor, and the soldier’s gun lies on a half-made bed.

“Look at this room, look at the room they have here. A palace. Let’s look a bit outside.”

Leaning out the window, the soldier pans across a ruined cityscape: building facades pocked by mortar, windows shattered by bombs, and entire blocks demolished by bulldozers. He turns the camera back on himself, gives a thumbs up, and smiles.

The TikTok post emblematizes a familiar genre of Israeli war media popularized in October 2023, when the Israel-Hamas war began, and now making the rounds in international press. For months, soldiers have been posing for the camera inside vacated living rooms or atop apartment complexes reduced to rubble. Bored as the war drags on, some update Tinder profiles with action shots. Their TikTok and Instagram reels show comrades smoking hookah, eating hummus, and praying in empty Palestinian homes. [1] [1] So as not to further disseminate and drive traffic to the images discussed in this article, only a select number of images and videos are included or linked as examples. However, all images discussed have been verified by the author.

Evidence of war crimes circulate alongside the more banal aspects of soldiering. In some scenes, soldiers play backgammon while sipping tea from plundered chinaware. In others, they drape captives in Israeli flags, forcing them to sing “Am Yisrael Chai”—“the people of Israel live.”

As an anthropologist who has spent time in Israeli military archives, I found many of these scenes familiar. Over the past 75 years of bloodshed, photography has long served to trivialize the atrocities of war.

The genre is hardly unique to Israel. But today the abundance of smartphones on the battlefield, ease of social media, and unapologetic militancy of Israel’s majority have made such war photography more visible than ever.

WAR TROPHIES

The recent photographic trend began soon after Hamas militants breached the Israel-Gaza border fence and massacred around 1,200 Israelis and migrant workers on October 7, 2023. As Israel Defense Forces (IDF) troops streamed into Gaza in the weeks that followed, many framed themselves as victors in a war of retribution. The monthslong operation has killed, to date, more than 30,000 Palestinians—the majority women and children—and so far has failed to bring the remaining Israeli hostages home.

Israeli social media continues to stream a montage of empty homes, blasted-out cities, and Palestinians abused or even mutilated by Israeli forces. IDF statements to international media have said the behavior “does not comply with the army’s orders” and “does not align with the expected morals and values of IDF soldiers.” But it is not clear whether any punishments or preventive measures have been issued.

In contrast, Palestinian social media documents the staggering human cost of the war: tens of thousands of civilians killed, and millions displaced to makeshift camps where they suffer hunger, dehydration, and disease.

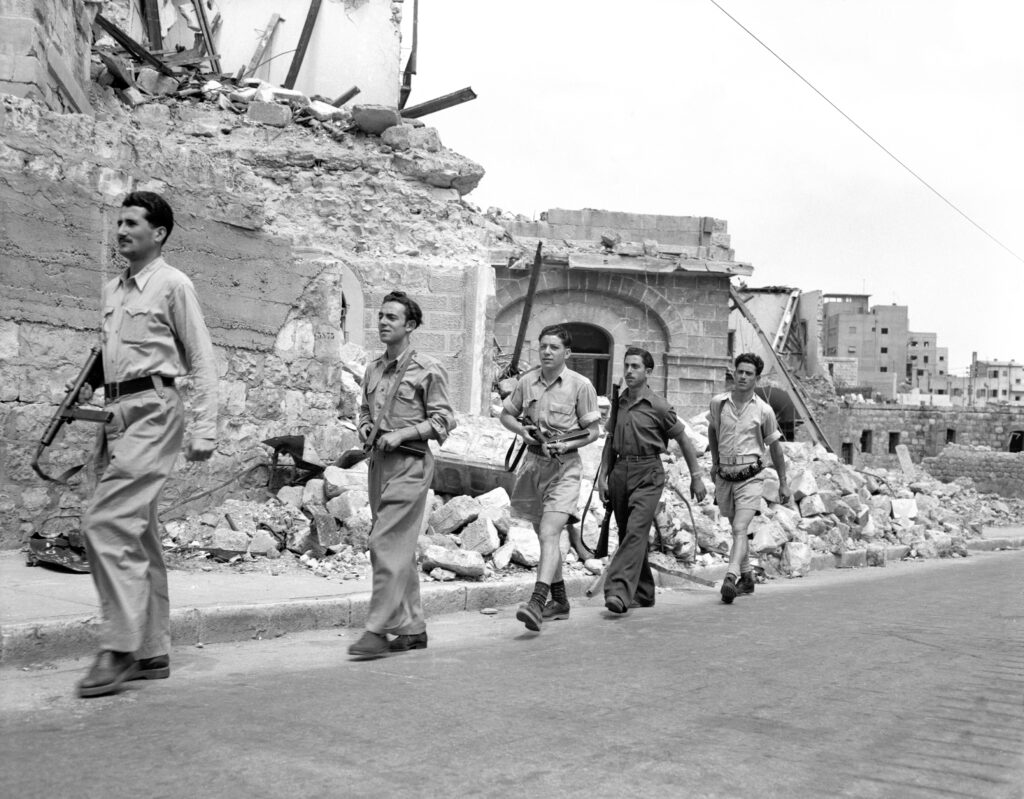

Precedents for the soldiers’ footage stretch back to the 1948 Arab-Israeli war and expulsion of at least 750,000 Palestinians from their homelands—the start of what Palestinians call the ongoing Nakba or “the catastrophe” and what Israelis remember as the war of independence. Then images from the battlefield were circulated by Israeli soldiers, military photographers, and journalists embedded in the military to evidence a resounding victory.

The most iconic of these images appear in critic Ariella Azoulay’s 2011 article “Declaring the State of Israel, Declaring a State of War,” published in the academic journal Critical Inquiry. Soldiers listening to records on a gramophone taken from a Palestinian home in the village of Salame. The ruins of Haifa’s old city, 220 buildings reduced to rubble to ensure those displaced would not return. A platoon erecting an Israeli flag in Umm Rashrash, now Eilat.

Some fighters took prints of these photos home, displaying them in their living rooms like trophies. The scenes narrated the atrocities of 1948, in the words of Azoulay, “as a series of unproblematic, quasi-natural events and justified as side effects of the state-building project.”

Anthropologist Rebecca Stein notes in the International Journal of Middle East Studies that similar images circulated immediately after the 1967 Six-Day war, when Israeli troops occupied the West Bank, annexing East Jerusalem and Gaza Strip, among other regions. In the taken territory, Israeli press reported soldiers “wander[ing] around with a gun in one hand and a camera in the other.”

Again, the photos marshalled all the destruction as proof of victory. Troops smiled in front of Al-Aqsa Mosque and prayed at the Western Wall. Israeli soldiers drove through the Palestinian cities of Jenin and Nablus in army jeeps, taking in the “exotic” views and the destruction. Staged after the blood had been cleared and the bodies carted off, the images, Stein writes, “served to stabilize and banalize” the military operations they represented.

Soldiers deployed into the heart of the Gaza Strip since last October are updating this historical archive. They may have grown up flipping through iconic photos of past soldiers grinning before destroyed villages, brandishing Uzis at the Western Wall, and plundering evacuated homes.

They replicated these scenes upon entering Gaza, juxtaposing their violence with scenes of religious piety, national pride, or just horseplay. Reels of troops playing on the beach or looting private residences play endlessly on TikTok while snipers on Instagram clutch machine guns in front of menorahs.

Over the past five months, such images have inundated my social media feed. While my scrolling hardly constitutes a systemic study, one thing is abundantly clear: The same old war trophies are being captured and circulated via new media.

FROM TEARS TO FLAME EMOJIS

Even as they represented Israelis as victors, earlier war photographs in Israeli media were often accompanied by lamentations. Israeli political leaders leveraged remorse to counter allegations, of which there were plenty, that the violence was far too brutal.

Such refrains sedimented into a narrative form—shooting and crying—that shaped how generations of Israeli writers and filmmakers have represented formative battles of the last 50 years. The 2008 animated war drama Waltz With Bashir, the 2015–2023 Netflix series Fauda, and more—this story type portrays the violence of pivotal military operations as regrettable atrocities that were nonetheless vital to Israel’s national survival.

As Hebrew and comparative literature professor Gil Hochberg notes, lingering on the injuries experienced by Israeli soldiers eclipsed the political imperatives of displacement, expansion, and settlement driving Israeli militarism.

But now there is a change in tone. Israeli soldiers are no longer shooting and crying.

They are shooting and dancing, shooting and grilling, shooting and praying, or just shooting and mutilating. Soldiers post TikTok reels from the frontlines filled with laughter, celebratory songs, prayers, and inspirational messages. Prominent politicians and thousands of regular users respond with exclamation points and flame emojis in widespread demonstrations of support.

The posts contrast grimly with the destruction in the background. But in a war of retribution, destruction is the point.

MARCH TO THE RIGHT

The genre shift maps onto Israel’s steady march to the extreme right over the last few decades. An occupation once framed as a temporary flex of military power has been embraced as a permanent status quo. Jewish supremacist ideology previously dismissed as fringe now enjoys the political mainstream. Nominal commitments to liberal democracy give way to an unapologetic embrace of authoritarianism, reflecting the global right-wing’s tendency to say the “quiet part out loud.”

“We’ve brought the entire army against you, and we swear there won’t be forgiveness” go the lyrics of the new hit Israeli song, “Charbu Darbu.” Playing in the background of many videos emerging from the frontlines, it has become an official anthem among the 400,000 reservists called up to war, especially the line “Every dog gets his day.”

Many government officials and their supporters are enunciating the expansionist aims of this war loudly and clearly. Right-wing ministers drafted plans for Jewish settlement in the Strip less than a week after troops rolled into Gaza. Others joined resettlement conferences attended by thousands. As unrelenting Israeli aerial bombardments have killed more than 31,000 Palestinians in five months, emboldened activists block roads to prevent humanitarian aid from entering the besieged Strip.

A DOOMED COURSE

Some international outlets claim most Israelis are not privy to the suffering in Gaza due to empathy fatigue, confirmation bias, or stringent military censorship of local press. Others report that algorithmically determined news feeds have prevented many Israelis from seeing images of Palestinian suffering.

But to say, “If only Israelis could see what is happening in Gaza, they would demand an end to the violence” ignores the political reality and majority. This is arguably one of the most documented wars in history. Accounts of the humanitarian catastrophe and mass death in Gaza saturate foreign press and the social media feeds of people worldwide.

The inconvenient truth is decades of war and dehumanization—tacitly supported by the United States and Israel’s other staunch allies—have largely closed one side off to the other’s suffering.

In 2002, amid the height of the second intifada—a bloody five-year period marked by suicide bombings in Israeli cities and military raids on Palestinian communities—the critic Susan Sontag observed, “[To] those who in a given situation see no alternative to armed struggle, violence can exalt someone subjected to it into a martyr or a hero.”

As 75 years of photographs attest, this has long been the case in Israel. But the sentiment may be more popular than ever: According to a survey by the Jerusalem-based think tank the Israel Democracy Institute, as of December 2023, 75 percent of Jewish Israelis opposed agreeing to the U.S. demand that Israel decrease the intense bombing of heavily populated areas in Gaza. Only 1.8 percent viewed Israel’s use of force as disproportionate.

Dissent within Israel to its military strategy remains fringe, but is spreading. In early March, 12 human rights organizations in Israel signed an open letter accusing the government of failing to facilitate humanitarian aid into Gaza, as ordered by the International Court of Justice. Thousands have attended protests demanding a hostage deal and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s resignation. Even demonstrations calling for a cease-fire are growing.

Ultimately, the war may be the current Israeli government’s undoing. The content streaming from the frontlines scaffolds criminal cases, sanctions on Israel’s political establishment, and unprecedented protests against Israeli war crimes abroad. Unending war for Israel may usher economic catastrophe, pariah status internationally, and rampant insecurity—forcing more Israelis to realize there is no military solution for decades of intractable occupation.

But in the immediate moment, the scenes from Gaza show refugee camps filled with millions who cannot go home and Palestinian children starved to the bone—as Israeli troops are shooting and dancing with glee. Nowhere in these images is a viable political future to be seen for anyone in the region.