The Strange Rites of Celebrity

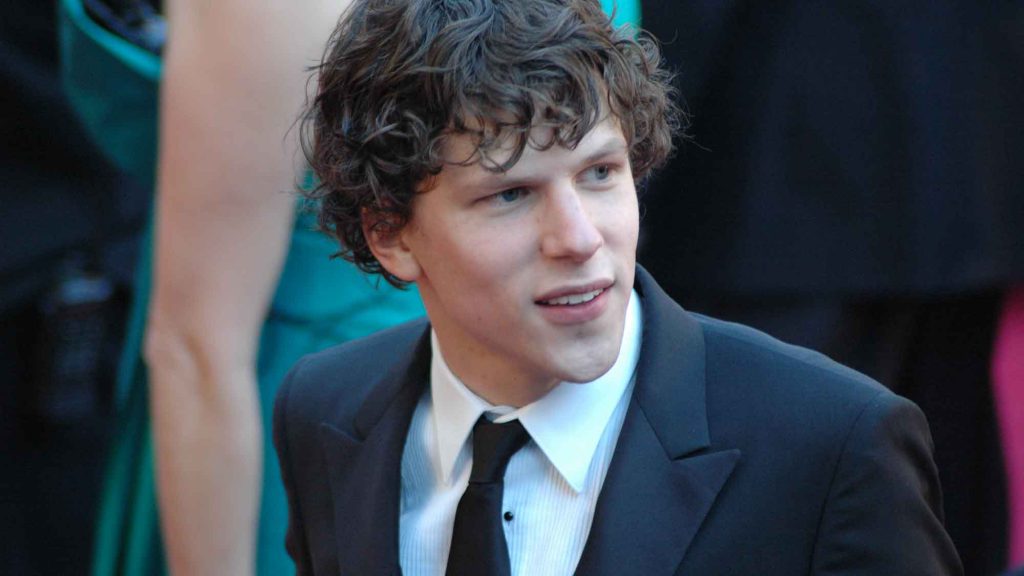

In the summer of 2016, I ran into actor and writer Jesse Eisenberg in the hallway of my local YMCA in Bloomington, Indiana. The star, perhaps best known for his portrayal of Facebook’s founder in The Social Network, wore an unassuming T-shirt with retro tennis shoes and the rimless oval glasses common among U.S. intellectuals. He walked quickly and purposefully, gazing at the floor.

The sighting was an unsettling experience. Without the lights and cameras of Hollywood, Eisenberg initially looked like a regular person to me. I wasn’t quite sure that the individual who was later sweating on the next treadmill over was really the star from Zombieland and American Ultra. Eventually, his identity solidified in my mind. It made sense for him to be in Bloomington, after all: His mother-in-law was heavily involved with a local nonprofit, where he spent a lot of time, and he had been vocal in the media about appreciating the rural city’s social initiatives and embracing a humble way of life. Once I had resolved that it really was Eisenberg, his presence seemed to exude specialness, famousness, and distinction. I observed something like an aura; I felt the weight of his difference from the mundane.

My first observation of this celebrity in real life was marked by both exhilaration and a nagging sense of discomfort. I realized that “celebrity” isn’t something inherent but rather a social construct that emerges through social interactions between the entertainment industry and the public. But was that construct a quality that Eisenberg carried around with him, or something that I had conjured up myself and projected upon him? Why did I feel in this moment of encounter more like a giddy fanboy than a social scientist?

As an anthropologist of the American Midwest, this firsthand celebrity sighting in my own ethnographic backyard made me think for a moment about how celebrity culture functions. The ephemeral, unreal world of celebrity came crashing into my very real world and made me think more acutely about power, celebrity, and hierarchy in American culture.

What made this collision even more interesting is the fact that Eisenberg himself is someone infatuated with anthropology and someone with a disdain for celebrity. Though I’m the one actively studying anthropology, ironically, it was a celebrity who helped me switch from fan back to anthropologist: to scrutinize my experience through a social science lens.

A perusal of media clippings about Eisenberg reveals that the social sciences, and anthropology in particular, played a strong formational role for this star. As an undergraduate at The New School in New York City, Eisenberg took classes in the social sciences (perhaps influenced by his dad, Barry Eisenberg, an associate professor at SUNY Empire State College with a background in the social sciences).

Discussing his love of theater with a British radio host in 2016, Eisenberg talked in detail about how college classes, especially those that explored the concept of cultural relativity (the idea that “there’s no culture that is better or worse; it’s just different,” as he said), shaped his worldview. In observing the world through a cultural relativist lens, Eisenberg explained, one must “look at other cultures and other countries with respect. And even if they’re doing things that you don’t like or things that affect you negatively, you know, that you look at their culture in an open-minded way.” In that interview, Eisenberg took issue with American exceptionalism, and in a brief political aside, he called for humbleness, openness, and respect for other cultures around the world.

The ideas of social science have shaped Eisenberg’s acting too. “There’s been no acting class that’s been as helpful, no writing class that’s been as helpful as learning sociology and anthropology,” he said in a 2015 interview. “What anthropology teaches you is that there is equal value to different cultural perspectives. And that is the best thing you can learn as an actor.” A villain, for example, may have equally justifiable ways of seeing the world or reasons for doing things; the key is to see the world from their perspective. Anthropology, he continued, “informs the stuff I’m interested in, the stuff I write about.”

Although making a career out of acting, Eisenberg has another identity as a high-brow comedic writer whose works have appeared in McSweeney’s and The New Yorker. In one of his first short stories for McSweeney’s, titled “Body Rituals Among the Lauxesortem,” anthropology is the main topic. (Hint: “Lauxesortem” is “Metrosexual” spelled backward, an established trick in satire and a nod to a famous anthropology piece about the “Nacirema,” or American spelled in reverse.)

“The anthropologist has become so familiar with the diversity of ways in which different people behave in similar situations that he is not apt to be surprised by even the most exotic customs,” Eisenberg’s opening line reads, in a direct echo of the first sentence from the Nacirema piece. The witty, descriptive cultural commentary turns a fictional ethnographer’s eye to the subcultures of urban America.

What if I take a page from Eisenberg’s book and turn an ethnographic eye to the event of the celebrity encounter?

According to ethnographer Kerry Ferris, who has done extensive research about fan and star interactions, celebrity encounters “reveal both the pleasure and the perils of radically asymmetrical relations.” There is indeed a huge asymmetry between the star and the audience. The fan may have an abundance of detailed and intimate knowledge about the star (not all of it necessarily true), while the star probably knows nothing about the fan. The power imbalance, however, is not as you might think: Yes, the star probably has more money, social currency, and control over speaking events, but in a random encounter, the fan may direct the tone. The star has much more to lose should the encounter go poorly.

Celebrity encounters urge us to think about social hierarchy and power in nuanced ways. Power is fluid and context specific, rather than innate. Hollywood celebrity figures are “American royalty,” as the saying goes, and as such, they enjoy the benefits of their station high in the American social structure. But as part of their social role, celebrities must pay dues to the system that benefits them. As Yale University professor of religious studies Kathryn Lofton notes, celebrities often experience dehumanization—viewers objectify the actor’s life work, identity, and persona, and turn those into products for public consumption. The celebrity encounter is one of the most vital rituals of a star’s commodification.

The saying that the stars are “just like us” isn’t really true: It conceals the social, cultural, and economic asymmetries at play.

These imbalances can make people uncomfortable, though most don’t stop to think about them or prepare for them. “I’ve been to acting school, and there is nothing to train you how to become an accessible human being,” Eisenberg has said. “People come up to me on the street and act as if they know me because they saw me play a character that feels like them.” It was not his intention, he explained in that interview, to create a personal relationship with the audience.

I never asked Eisenberg about these things myself; in the moments that I have run into him, I was too star-struck to engage him in deep conversation. I was worried that he might identify me as yet another super fan and that I would infringe on the small amount of public freedom that he has.

Eisenberg has tended to resist the pressures that emerge out of celebrity. One journalist described the actor as “uncomfortable with his celebrity status.” As another commentator said, Eisenberg prefers “to exist as a kind of anti-film star.” He keeps a low public profile; he exercises at the Y.

From my encounter with this Hollywood actor, I came face to face not just with stardom but with the American social hierarchy. Anthropology gave me the tools to analyze this strange cultural encounter for what it was: an awkward but important ritual of exchange between different parts of the human social network.