Do You Want to Write for SAPIENS?

Ask SAPIENS is a series that offers a glimpse into the magazine’s inner workings.

The first step in writing for many English-language general audience outlets is “the pitch”—a short proposal to editors about what you would like to write. Learning the pitch is itself an important skill that is a necessary and important step in public writing. In this workshop, you will have the chance to learn the ins-and-outs of pitching, draft a pitch, receive feedback, and discuss popular writing strategies. Join Chip Colwell, the editor-in-chief of SAPIENS magazine, to develop or deepen this vital practice for aspiring or seasoned public anthropologists alike.

CART captioning by Sherri Patti.

>> CHIP: Hello, welcome, we’re going to let people filter in here for a minute or two.

>> CHIP: Hello, welcome, we’re going to let people filter in here for a minute or two. Well thank you for joining this webinar. It’s really wonderful to see so much interest in publishing for public outlets and CVNs, more specific, my name is Chip Colwell and I am the editor-in-chief of SAPIENS Magazine. We are a publication of the University of Chicago press and we’re funded by the Wenner-Gren Foundation and we have a really amazing, amazing team of editors who work really hard to make anthropology relevant this the world. To bring anthropology to diverse publics and to help trained anthropologists become much better writers and better at engaging with publics.

This truly is a craft, it’s a skill that’s developed. And it’s not often taught in universities, in graduate programs, and other places.

So our team takes really seriously not just the work of getting anthropology out in the world but helping anthropologists themselves become better public scholars.

So as we proceed this morning here in Denver, Colorado where I am, just a few rules. I ask that everyone try to be present, meaning turning off e-mail or other distractions.

Do your best to be engaged. We have here a chat function so if you have questions, please save them for the end. It’s a little hard for me to toggle back and forth with the chat during the workshop but I’m really happy to answer questions.

And I left some time at the end to be able to work through them so please be engaged as we go. And also be helpful to each other if there are any questions, feel free to jump in and ask those.

We encourage everyone to be respectful for each other, to each other on chat and otherwise. And just a note that truly everyone belongs here this is really meant to be a space for everyone to learn and to be together and to help deepen their own craft in public communication. And also note that this is a bit of a participatory workshop which is a little challenging in this webinar format but I will invite some ideas as we go along. So I encourage everyone to have out a piece of paper, if you have one available, or pull up a Word document or other kinds of writing program. Just so you can begin to start, begin to really develop some of those ideas for yourself as we go along in this webinar.

This weapon familiar does focus on something that’s called the pitch. And the pitch is a kind of proposal. And a kind of abstract that people submit to different kinds of outlets. That they might want to write in. So you can think of it as a kind of almost mini grant proposal if you’re coming from the academic world. Think of it as a kind of mini abstract that outlines your vision for what you’re going to be writing about. But it’s a very, very specific kind of genre. And so part of the work that we have to do as anthropologists who want to write for the public is to master this skill and this craft and this genre of the pitch because if you can’t get an editor or an editorial team excited about your idea through the pitch it’s really hard to get to the next step to publish your work in full form.

In full flowering in the outlet that you may dream of. At SAPIENS we do use the pitch process. And we use it because we want to use the magazine as a tool for anthropologists to learn these skills. Because if you go to most other mayor English language newspapers and magazines as well as many non-English language magazines and newspapers, this is a skill that you’re going to need in order to be successful in getting your work out to the public. So the pitch itself involves typically two different types of writing that you’re proposing. The first is an essay and this is a kind of narrative that is going to take the reader on a journey of discovery. So most typically, this is very much in the format of storytelling, where you have often an opening dramatic scene, you have some main characters, you then have a kind of climax and then you have a resolution and then something about what happens next. So typically, not always, there’s many different ways of storytelling of course.

And at SAPIENS we welcome multiple forms of storytelling as do many other major outlets but your typical essay is going to have that kind of arc. It’s going to take someone on a journey and you’re going to discover something along the way.

An oped or an opinion piece really describes a very specific form of writing.

And this is a form of writing that shares an opinion about a problem and proposes a solution.

So an oped or an opinion piece may start with an anecdote or story and may have some kind of storytelling elements to it but this is much more of a debate style piece, much more of an argument. Typically you start with an opening it could maybe a comment about something happening in the world a statistic, maybe it is a story.

Then you move into your background for what’s going on and then you would have two or three arguments about the problem and how you see it. You would have a response to a potential counterargument and then you have your answer to your solution.

So opeds are typically quite formulaic and it’s important to follow that formula. And it’s really argumentative you’re offering your perspective in an important debate. Now for the type of outlet or the place where you’re going to pitch, there are truly, you know, hundreds and hundreds of options today which is so exciting. And really what’s so exciting about being a public anthropologist right now.

And, you know, I’m, myself, am a — I come from an academic background, I have a Ph.D. in anthropology, I have done academic research for more than two decades and I’ve been a public anthropologist for about 15 or almost 20 years now. So I really see this from both perspectives and one thing that has been so exciting in the last 20 or so years is to see how there’s more and more opportunities for anthropologists to write in more and more places. This is just then a very, very small list of kind of a North American focused sample of places you might consider writing just to show the differences between some places that publish an essay, some places publish really opeds and some places, some venues or outlets will publish both. So, for example, naught lis which you see on the essay side.

Tends to really focus on that journey of discovery kind of essay and you very rarely if ever will see an argumentative debate style piece. What’s important to note too is that for the essay if that’s what you’re interested in writing which typically is about 2,000 words,

once it’s published, in most of these venues in any case you can have longer or shorter form but I think 2,000 words is what your target would probably be and if you want to write that you will almost always need to submit a pitch in most major outlets.

Whereas in an oped for quite a number of venues for the Washington Post you draft your actual oped first and you submit the oped really without a pitch and some places require both a pitch and the oped itself. So in short, you kind of see the different ways these venues will invite your work. And so it’s important to find those venues, look at their — how to submit page or how to write for us page and then adapt based on those requirements. A really common question is, how do I know which outlet is right for me?

And for me, there’s about five key questions to begin with. The first is audience. So if you, for example, are writing a pretty high level

policy paper about, let’s say, you know, it’s about immigration, international

policy. You probably don’t want to write in somewhere like Slate which is kind of more poppy and more conversational. Somewhere like foreign affairs, Washington Post, New York Times, Wall Street Journal those would be the right audience, right?

Because you’re trying to talk to policymakers, perhaps people who are making important decisions around the particular issue.

So first and foremost think about your audience. Who is it you’re trying to reach and what venues are they likely themselves to be reading? Secondly, think about the tone of your writing, you know, if you are writing a really kind of fun piece with maybe it’s a jokey or sarcastic tone to it,

foreign affairs or the Washington Post may not be the right venue for you. You know, somewhere more like maybe a fashion magazine or an entertainment magazine, those might be a better fit for you, rolling stone, something like that. So think about how you’ll approach it in terms of tone.

Then think about your anticipated word count this is really quite important because most venues, their editors know what they will publish and the upper limits for it. For example at SAPIENS most of our pieces we ask for the first draft for essays to be about 1500 words so if you have a 5,000 word essay in mind or a 6,000 word or true long form essay,

then SAPIENS is not going to be the right place for you because editors are going to notice you’re proposing a 6,000 word essay. But we don’t publish that. You want to go to a long form venue called narratively. You may want to think about your goals about how likely it is to be accepted.

If you’re trying for a really competitive kind of high tier outlet, such as the New York Times, it’s really important to know going into that your chances of success are really quite modest, some New York Times editors have talked about how about 95% of their opinion pieces are

invited. And that really only leaves about 5% of their published pieces open for pitches.

And everyday they’re getting hundreds of pitches so the chances of your particular one finding a place there is relatively modest. Doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try it, it just means that if you have a goal of, you know, I need to get this idea out by the end of the week the New York Times may not be the best venue you might look at your local newspaper or other places that have a

less competitive acceptance rate and then it’s really important to scan whatever venue that you’ve identified and think about what you’ve published similar. On the other hand you do want the venue to have published something in that vein or on that subject area but not too identical so that it feels like it’s repetitive.

In other words that first part is, you know, again, say you’re writing a humorous piece and you go to a venue and there’s no humor at all that’s because they chose not to publish any humor so you need to match the tone and approach of the targeted outlet.

But if that outlet has published something on a very similar topic making similar arguments then your odds are going to go down because most editors don’t want to be repetitive either in their content.

So what does a pitch look like? And this is a really amazing resource that’s a little hidden on the internet but I would encourage anyone who is interested in pitching to go to it and check it out. So this is a website called the open notebook. A kind of magazine for and by mostly science journalists and journalists at large.

And there’s an entire database of pitches and these are real pitches that have been submitted to a host of

venues and outlets. So as you can see there’s a series of drop-down menus where you can actually say you want to try to submit a pitch to the Atlantic. You would drop down, you would click the Atlantic and see examples of successful pitch to the Atlantic. A truly successful resource. Use this, return to it, it’s constantly being updated. And

this is a great way for you to model your own pitch and your own writing.

So this morning I’m going to focus pretty heavily on SAPIENS. And I am doing that because hopefully many if not all of you are really interested in pitching us here at SAPIENS. But additionally because what we do at SAPIENS is pretty close or very close if not even identical to many other magazines and newspapers. So

what you’re seeing here and what we do really is pretty common really throughout the industry. So

I’m doing this to encourage more pitches for SAPIENS and better pitches for SAPIENS and helping you to develop the craft to write for us but also this is really a skill that you can take absolutely anywhere so if you’re interested in writing for SAPIENS go to SAPIENS.org/write.

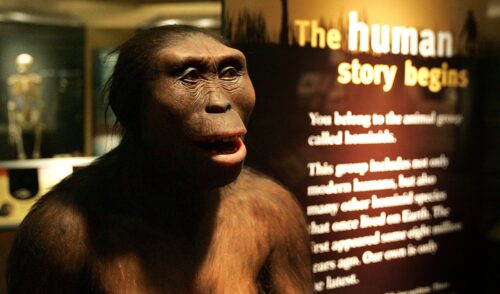

And you’ll see our pitch guidelines where we have pretty extensive descriptions of what it takes to submit a pitch to us and what kind of pitches we’re looking for and the writing itself. One thing about SAPIENS is that we truly are geared towards bringing that anthropological lens, bringing anthropological research

to broad audiences so we do have that focus on anthropology and the training component of the work that we’re doing that the editorial team really wants pitches from seasoned writers, maybe this is your first attempt at public scholarship and we

want to help you be successful in developing this craft, and it is a craft, I feel like I can’t emphasize that too much because the kind of writing, the kind of approach, even the kind of mindset that it takes to go into this work is really different and just as a bricklayer or an artist needs many years to build up their craft,

so too is the case with public writing. At SAPIENS,

you know, we are our primary audience is the public or general publics. We understand many other anthropologists or colleagues will write for us but our mission is tied to the general audience think of your cousin, your neighbor, your barista, your mail person, those are the audience members that we’re really targeted on. We do publish anthropology but it’s really broad did I defined in a fore field way.

And we are really look for people who are grounding their ideas and work in anthropology. We do offer an an rare yum of 250 dollars per published piece.

On the question of payments at other venues you see some that are

… that will pay up to maybe a dollar a word. Sometimes you’ll get a flat fee like we do at SAPIENS. You might expect $500 or around there for some other venues and then there’s many where you don’t get paid at all so most newspapers, opeds especially, you’re typically not getting paid for those. It’s also really important going into this work with us if you are interested in

SAPIENS in particular that we do have a really collaborative editorial process so what that means is that the editor, if your pitch is accepted is going to work really closely with you to develop your piece so you can expect multiple rounds of edits, lots of back and forth in conversation and the goal is really to work together to help you

learn the process but also to have a really amazing product. Something out in the world that you’re proud of and can stand by.

And on that note, you know, SAPIENS is unique that way. Many other venues, especially kind of when you get up in the hierarchy of outlets,

you can expect in a sense not, you can expect not as deeply a collaborative process. So, for example, at many venues, you won’t have any choice in the images.

That may accompany your piece or the title or the teaser, the description of the piece.

There may just be editorial’s decisions made because the editor decides this is the best way to present the information.

So I don’t want to overstate that either. I mean typically most editors, they equally want to work with you and want you to be proud of the work but there’s often a very firm hand in the editorial process and that’s something to expect when you go into it.

So what should you expect if you were to write for SAPIENS?

So to begin with, the very first step is to submit the pitch. And, again, this is the summary of your idea for a piece. Within a particular publication category and story type so you’re typically pitching saying this is an essay or this is an oped or even more descriptive, you know this is an essay that is my personal journey or this is an essay based on my research.

So indicating

the kind of type of storytelling you want to do as well. So, at SAPIENS we have an annual deadline of March 1st. We also very occasionally

will accept pitches throughout the year for truly urgent topics or for our editors invite a pitch based on a gap in our publication calendar but in any case we have our editorial team review your pitch. And if it’s accepted an editor will typically ask for the first draft within about four weeks.

There can be variations here. But something really urgent we may ask for a draft within days. If it’s something much further out, what journalists will call an evergreen piece, something that can last for a long time, like an evergreen tree, then,

and we’re really backed up with our queue we may ask for something further out but typically you might expect to have a draft ready within about four weeks so then your development editor, so this is the editor assigned to you that will develop your piece with you, collaborates with you to define your piece.

Typically there can be multiple rounds of edits for this and in terms of timeframe when you receive your first edits we’re usually asking for the next draft within a few weeks. So after this back and forth development you and your editor have something that you think is pretty much ready to move forward with. It’s 90 plus percent there so it’s finalized. We then have additional editors review the piece at that point.

So in the journalism world those are called “top edits” or one last high level look at the piece by another editor. And then additionally we have, at SAPIENS and again you’ll experience most other places, a copy editor, and

/or a fact checker will look at your piece and at SAPIENS as many other venues when you turn in this piece you’re going to include some annotations so footnotes or just as you would in an academic piece, you know, all of the

articles and books that are backing up your claims. And those are checked by an editor. So once everything is

finalized there you’ll then see those last edits from the copy editor approve those. At SAPIENS, we also work with you to develop the images that you would might being to use that you would like to see

we do as an editorial team typically make the final decisions because we have expertise of what works best for titles to get readers to

your article and also which images can work best. There’s technical requirements and stylistic requirements and so on but we share all that with you and

also invite input on how to best promote your piece. So then it’s uploaded to our website, it’s reviewed and it’s published you’ll receive an e-mail upon publication. And then we ask that you help promote the piece in your networks.

And then at that point once everything is completed we provide you the paperwork for the honorarium. So that is a

n overview of writing for SAPIENS but again very, very similar processes for most other venues of what you’ll see.

And so at SAPIENS, we publish a whole range of different types of writing, non writing, video, multimedia content.

Illustrated essays, photo essays and more. We’re really open to the full range of possibilities of anthropological storytelling. That being said, most of our pieces do fit into the essay format or the oped format.

And that really is the bulk of what we’re working on and that gets published in our pages. We also do publish poetry and for those that is not a pitch process but the poems themselves are submitted to us for our review. And for all of these we really want a

an actual pitch. There’s the exception being the poetry and if there is fiction or personal essay, those, because they’re so dependent on the execution of the writing itself we ask for a sample for that.

So we encourage you to look at SAPIENS.org, look at what we published. Really, the best kind of writings often come out from the best kind of reading so look at what we’re publishing, read it critically, analyze the work that’s being done and that gives you a sense of the kinds of articles we’re looking for and then the kinds of pitch as well.

So we review the bulk of our pieces at our March 1 deadline. And we make those few exceptions throughout the year.

And the pitch process is really necessary for our editorial team. We have a lot of people that want to write for us. The pitch process helps us to evaluate the potential for the piece. This is why the pitch process is developed for

editors across so many magazines and newspapers but it’s also actually very efficient for you as well. Right? So rather than having to write a 1500 word essay that is just perfect, all you have to do is write a 2-300 word summary of what it is that you want to write.

So it’s actually less work for you as well. At SAPIENS, when we get a pile of pitches every March we

evaluate them individually, multiple editors are looking at each one and we’re evaluating them based on a few key criteria. We’re first asking is this grounded in anthropological insights. We get pitches sometimes that are really wonderful that, you know, maybe have a lot to say, they’re on an important topic.

But it’s hard to see where the anthropology is in them so you need to make clear where the anthropology is. Secondly does it have a clear and compelling message at its core? So is there a central idea that is also very compelling that clearly comes through for the editors?

Then, does it have a clear storytelling component or an argument? So if it’s an essay does it have a clear storytelling component or if it’s an oped does it have a clear argument? Is the author well prepared to tell the story or make the argument?

So a lot of times we may get a pitch on, you know, a very important topic, but the person doesn’t have the expertise or authority to necessarily speak on that topic in a way that general publics would immediately be able to identify. So the example

I am sometimes given is how, you know for me I’m really invested in issues of climate change. But I’ve never written academically on climate change, I’ve never received a grant, I’ve never received an award, I’ve never done any research on climate change itself. But I have done a lot of research on

the issues of returning sacred items and ancestral remains from museum to tribes. I have written numerous books and have grants and so son so I have that sphere of authority and bring that immediately to a popular writing piece.

So an editor seeing me pitch on climate change is going to be a little more skeptical. On where I am coming from and what I have to say versus on if I have to pitch on repatriation. It’s also important to think about is this a timely story or argument and/or does this add new viewpoint to current conversations?

So most editors are going to be asking themselves is this writing, is this argument, are these ideas relevant to our world right now?

Is this something that people want to think about, read about, talk about, share with their circle?

And is this adding anything new to a conversation or is this just repeating what has already been said in many places, in many ways. So that sense of novelty and the sense of currency are both really important TO

to be able to express in your pitch. And at SAPIENS we truly do understand that many of you maybe have never pitched a magazine or newspaper before, and that’s not a problem. You know, we understand this is going to be a new process for many scholars.

We understand that your pitch may not be perfect. But we want to see that at least you’re following some of the basic guidelines that we’re offering and some of the

basic strategies that we’ve laid out as well. So I appreciate, you know, you’re making huge headway just by being here today but also do check out the resources that we have on that pitch page and also

in this specific essay around how to pitch us at SAPIENS.

Okay. So, for the last part of the this workshop we’re going to move into the craft of writing itself. So what I’m going to do is provide some examples of

a really simple straightforward even formulaic way to organize your pitch. But this hopefully simplifies things for you to make it really clear around about how to shape it, how to structure it to make it successful.

So there’s going to be a three part pitch and we’re going to go through each of these

parts, let me give you some examples, I’m going to give you a little bit of time to draft some initial ideas for yourself as well. Get out that piece of paper or bring out that digital document so you can do a little writing as well.

So the three part pitch begins with a paragraph that provides a brief story, an anecdote, something that’s going to really pull the reader in, show them what’s at stake, who the characters are.

And why all of this pointing towards why all of this begins to matter. Then, in the second paragraph,

you can state very, very clearly what it is you want to write, so this is where you say here’s my argument, here’s the point to the story, being totally unambiguous about that. So often

an option too in this paragraph to say a bit about who you are if that’s not covered in your opening story. Sometimes that opening story puts you as one of the characters as maybe you’re out doing some research can or maybe it’s an experience you had.

So you may have done that by the opening paragraph but if you don’t you want the editor to know things like I am an anthropologist who has studied this topic for so many years and so on in the second paragraph. In the third paragraph this is where you can summarize what your narrative is.

Who your characters are and why your story matters right now.

So this is a paragraph that kind of gives a try shape to the story, right? The opening is kind of a teaser. The second the here’s my point or argument. And then the third is he’s the big picture, here’s how the narrative is going to unfold.

Here’s the people that I’m going to be writing about and this is why this needs to be published right now.

Okay. So it’s important to do your best to nail the opening with a story.

Especially for essays, opeds, you might think about more of a laying out your argument right now abut the essay, you really want to be able to give — the editor a sense of not only what the story is but you want to be able to demonstrate that you are capable of telling a really good story because stories are the means by which we’re going to pull in public audiences.

And get them engaged with our ideas so storytelling is truly at the heart of this work.

This is an example of — I’m using with permission, K of of somebody who we worked with who drafted two pitches for us.

One their first attempt and then secondly, after working with us and developing their pitch. And so this is the one they first sent in as their opening paragraph.

(Reading). So for an academic this is a clear set of statements. A very important question for academics but also society at large. But there really is no sense of story, there’s no sense of really what is at stake in someone’s life. This is an academic idea that’s being put forward. So we want to

set aside that academic part of our brain and not try to lay out a

kind of academic concept or an academic problem but instead find a story that illustrates this point.

So here is our colleagues’ second attempt. (Reading).

Here you see the same ideas at play but you’re brought into Jerry’s life. The author shows the true trials and tribulations of an important actual person.

And then he brings us to this question of what happens that when life outside is harder for people than life inside a prison.

So you still have that question is there but there’s the story that leads you to it. And draws you in.

So with that I’m going to give you just a minute or two here to scribble some notes, imagine what would that opening story be for you? If you’re wanting to write something about

the topic that’s most dear to your heart right now, what would that opening story look like?

Okay so let’s move onto paragraph two so what do you want to write and who are you if you haven’t covered that yet. So again, here’s our colleague who

offered this as his first attempt. My interest is in asking questions. . . (Reading)

again using a bit of jargon, insiders know exactly what this is speaking to. Understand the ways in which this, the academic journalists establishes a certain form of authority. But for an editor who may not have any background in anthropology, who may not have any interest in the academic world, this is really

a bit too thick and too hard to follow for it to be compelling. So we’re going to again, set that side of our brain to this side. And bring in more of our

thinking about just being as clear and straightforward as possible for nonacademics using very clear straightforward language and

showing your authority in who you are in a bit more of a way that lends authority to this particular piece.

So in this 2000 word essay I take readers on a journey (reading).

So here what you get is some really good important details, how long this is going to be. You know, the statement I’m going to take you on a journey makes very clear that this writer understands that this essay is a journey. It’s also

the story itself is based on a yearlong investigation so this story is based on this particular research.

And then there’s some additional credentialing around being a Ph.D. candidate and being a community organizer. And then instead of emphasizing the academic publications this person has said, has smartly emphasized their popular writing which shows editors, okay, this person has done this before so they can probably do it again.

So I’m going to pause here for another minute. Just to allow you to sketch out some of these initial ideas so imagine based on a first idea, okay, you’re going to tell a bit of a story, now how is it that you will help the editor understand what it is you want to write? And who you are. Why you are the person to write this story.

Okay we are already two-thirds of the way through the structure and we are on paragraph three which emphasizes the narrative, the characters and why our story matters so again our colleagues’ first attempt. (Reading).

‘s first attempt. (Reading). So this is again a bit wrapped up in some jargon. It would be typical for scholars to provoke more questions but most people are reading, most popular outlets and their audiences they are reading because they want answers not because they’re looking for yet more questions.

And the notion that this is merely a case study can work. For a particular kind of audience but we want to broaden the possible audiences but yes, people are interested if Mexico but what about people who are interested in the industrial prison complex more broadly. And then an argument that

anthropology can contribute to this conversation is going to fall flat with a lot of editors because they’re going to care less about that claim in a general sense and understand how are you going to actually prove that, to show that anthropology contributes to this distinctive conversation.

Not specifically that anthropology as a field has something of value to offer. So, again, this is not what most editors are going to be looking for. Instead they’re going to be looking for something like this. This essay will begin with (reading).

So well stated in this next draft where you’re still linking Gerry’s story but what does Gerry’s story have to say about the biggest questions facing all of us as policymakers, you also get a sense of the flow of the piece itself how it will go from Gerry’s story of pulling back and then back TO

to — pulling backout wards and then back Gerry’s life and landing on questions that really matter in the world today.

So this is your third paragraph, what your narrative is, fleshing out the characters if you need to and then why your story matters right now and so with that I will give you another minute to make notes on how you might approach this in your storytelling.

So we’re putting all of this together in a single pitch and some of our editors will say pitch us and typically that’s going to be about 200, 300 maybe 350 max if you’re putting it as a single

chunk of writing, other venues such as there’s a really great one for academics called the conversation they’re going to break this up for you and ask you for these sections individually but whether it’s kind of individually or this longer version, you are putting this together as a single pitch, so that a few

vital questions are going to be answered for your editor. The first is what’s the story? That’s the very first question any editor is going to be asking and then ask why you? Why are you the person to write this story? Why not some other academic or some other person?

So what? Why does this matter? Why does this story need to be told right now?

So if you can write a pitch that really pulls together those elements, what’s the story, why you, so what, why now? You’re going to be in a really good shape? And the probability of your pitch getting serious consideration is going to skyrocket.

It is important to note here too that maybe you’ve written the perfect pitch. Maybe you’ve truly nailed this and your pitch still isn’t going to be accepted and there’s lots of reasons for that, you know, maybe the

magazine or outlet that you’re pitching already has a really identical story in its pipeline and you haven’t seen it published yet so there’s no way you would know but the editors aren’t going to want to replicate a similar story so close to a new publication that’s coming out. It could be that

the editor that might take on your piece because of the subject area already has a really long queue and they are being so highly selective they are picking almost nothing up. There’s a whole host of reasons for why even really good pitches may not be accepted. So

for me what’s important there is to not dwell too much on the no if a magazine or outlet passes but rather to really evaluate, you know, am I doing these things right? Am I approaching the pitch in the correct way? And if the answer is yes and yes keep pitching and trying and you will find success.

And it’s really important to practice this pitching. This really is its own genre, its own way of thinking and writing so don’t try once and expect to

be perfect, you know, this really is something that you can work on and continue to develop. So

practice this pitch, this is the formula, again, sort of like jazz, both for the pitch and the writing itself. Once you get the formula down you understand the basics, you can elaborate on it and go in different directions, be far more creative but especially when you’re first starting out, this is the formula to stick with.

This is what editors will want and expect and be grateful for because you are making their life easier by showing that you understand what they need to quickly evaluate your piece and whether it’s the best fit for their publication.

So with that, we have about ten minutes left for any questions. So thank you, all so much for your attendance here. I’m going to stop the screen share so I can read the chat.

Great, so please put any questions that you have in the chat or the Q&A function. Sorry, it looks like the chat has been — I’m just catching up here on some of the Q&A. The chat’s disabled. So I’m going to turn to some of these questions now.

So what does it mean to be a public anthropologist, the way I’ve been using it and the way I conceive of it at SAPIENS is this is not doing academic work in the public sphere but rather translating the work of anthropology for general publics. So this is the work of making

your ideas, your discoveries your research accessible to general publics. Is there any particular expertise required from authors? It’s really dependent upon the

idea that you’re pitching so in some cases the expertise

might be relatively light, you know, this could be, if you had to say an amazing experience in the field and you were just sharing that single experience you don’t necessarily have to have a Ph.D. and books and so on and so forth but if you’re writing on some topic that’s highly technical,

that really requires a deep knowledge of that topic, then being able to demonstrate that at least to your editor is really important so that’s where you’d want to

ensure that the story you’re telling and your authority expertise are really matching.

Is fiction writing included in types of stories that can be shared? Absolutely.

Beyond SAPIENS for sure, you know, there’s a lot of amazing fiction writing that goes on if you’re familiar with the journal humanism and anthropology and they publish really amazing fiction. And then at SAPIENS we do occasionally publish fiction in fact we had one just a couple weeks ago if you look at the website of dreaming being outlawed in cashmere.

So it’s something we do occasionally look at and consider if that’s something you’d like to pitch us.

So is it necessary to have awards to be published at SAPIENS? Definitely not, we understand a lot of early career scholars might be writing for us and, you know, those things tend to come along a little bit later in one’s career. And there’s all kinds of reasons why people might have had opportunities to get grants and others not so much, right?

What we’re really looking for again is that connection between the idea that you’re writing about, that you’re pitching the story you want to tell and your background. And do I have the authority, do you have the experience to tell that story, are you the right person to tell that story?

So it’s really about the why you question that we would like to understand and so there’s no kind of requirement around numbers of grants or awards or publications, it’s about the fit of the story you want to tell. And your background.

Does the subject of the story need to sign off on their name being used? No. So if I understand this correctly, you’re asking if the people in the stories can be anonymous or can we use pseudonyms for those folks and the answer is yes. We do this in anthropology all the time. Journalism not so much. But

when there’s a good reason for it, especially if

you know, there’s maybe a dangerous situations or so on the answer is yes. We want to ensure all the ethical requirements of our discipline and journalism are being followed so we trust that the anthropologist’s are writing about particular people that they have gone through the concept process and anybody that they’re writing about has given them consent for that research.

And do we have template release forms for photo essays?

we do not have those forms, again we look to the authors to have those permissions in place. And

in cases where the author does not have permission for images, but would like to use images our editor can seek those out at times but it’s less about forms and it’s about certain kinds of consents that we’re asking for.

How many people read SAPIENS monthly? A great question. And it can vary quite a bit. We get about historically about 3-5 million page views. So that’s individual reads. Every year. At SAPIENS. So

that ends up being, you know, about 200-400,000 page views a month. But it’s really unpredictable around how many people will read your particular piece we see sometimes

it might just be two thousand people will read your piece. We have some pieces that were read by half a million or a million. It can vary quite a bit and it varies quite a bit around these questions of are we be really convincing around the expertise, around the why now, the why you, is this really relevant, are we using the right storytelling to make this a captivating read that people are going to share.

Are we answering questions that Google and other search engines are identifying that you can get the answer there? So it’s really kind of a complex set of strategies that we use to try to of course get as many readers as possible but the actual reality is you can expect a pretty wide range between what’s read a lot and what’s read not as much.

The question is here around my characters in the story are the hunter gatherers who lived 50,000 years ago, I would like to ask if arc owe logical stories are tole through artifacts are accepted? Love the question. Because a character does not have to be

someone that walks around and talks like me. Characters can be all kind of things, a character could be a virus, a stone tool, one of my favorite stories where it’s a chick in pa pew what. Characters can be — take many shapes and forms.

The main thing is having a character if you’re doing that storytelling.

New sources frequently pick up and recycle stories from other outlets. I’m curious which stories are picked up and circulated by other outlets? Probably what this is partly referring to is the ways in which especially for sciencey type pieces,

begin their life as a press releases. And so press releases, about new research discoveries are put out in the world, someone writes the story and that new kind of species or something like that and that’s picked up and told in slightly different ways. We don’t really do that very much, we’re very much more we want to hear from the researchers and have them tell their own stories rather than journalists covering it but we do republish our pieces quite widely so a number of our pieces are

regularly republished in Smithsonian magazine and in the Atlantic and discover and a lot of other different venues as well.

What if you have never published before? It’s helpful if you do have a bit of a track record but not necessary. For SAPIENS or most other places you got to start somewhere. Everyone recognizes that. So just go for it. Get some experience and

try to build on that. Is having other writing examples available online? Like a blog but not necessarily other publications helpful in boosting credibility or does this really not matter? It doesn’t matter so much especially for the other high level venues they really want to see a formal publications in other outlets so a blog, that may help you with your own writing.

And it’s great, but in terms of giving you kind of credibility with other editors not so much.

And I am peeking ahead so I think where we’re at at the hour we’re going to need to wrap things up. But I really appreciate all these questions.

My e-mail is chip@SAPIENS.org.

Please e-mail me if you have additional questions, if you asked a question here and I wasn’t able to get to it. I really would love to hear from you to talk with you further. That’s a part of my job and something I’m genuinely passionate about and really excited about. So Chip@sapiens.org please do reach out to me and I hope we have the chance to see your work.

To work with you TO

to help you grow in the craft of public writing. So thank you so much for attending today’s workshop and I hope to cross paths with all of you in the future. Take care and thanks.