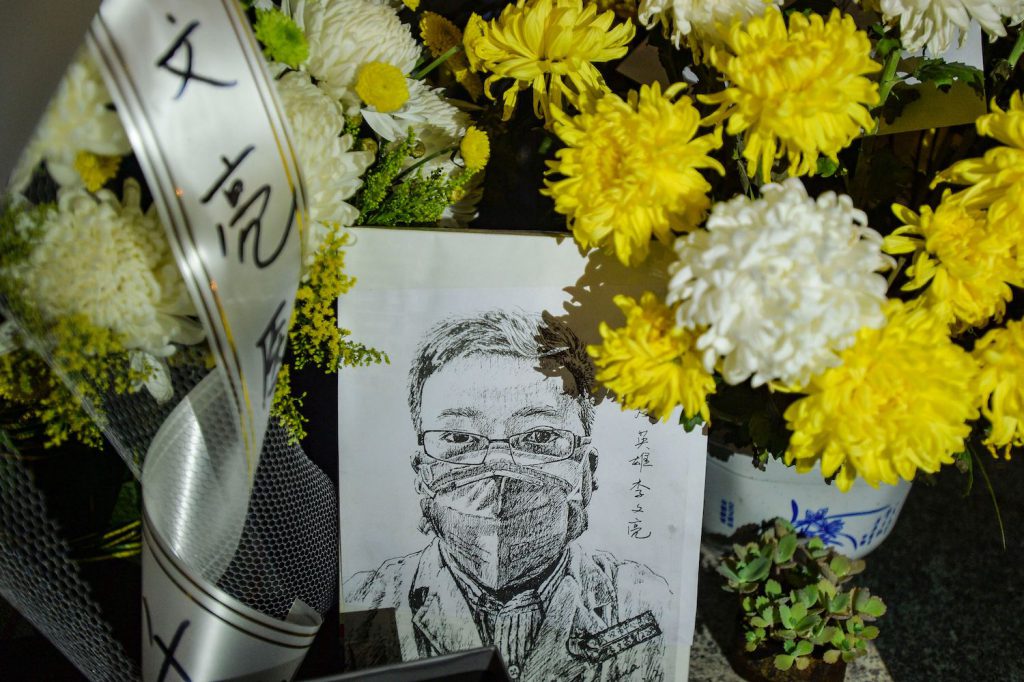

How Dr. Li Wenliang Went From a Whistleblower to a National Hero

On January 3, 2020, Li Wenliang, an ophthalmologist from Central Wuhan Hospital in China, was summoned by local police. His crime? A couple weeks earlier, Li had shared an image of a diagnostic report with some fellow doctors on the popular messaging platform WeChat. The image, which showed a patient infected with a novel strain of the SARS coronavirus, ended up going viral.

The police accused Li of “making false comments” that “severely disturbed the social order.” The doctor was asked to sign a warning letter agreeing to stop spreading “rumors” about the virus, or else face prosecution.

A little over a month later, Li passed away after contracting the coronavirus.

Readers may remember this story. The warning issued to Li, and his subsequent death from COVID-19, led to one of the largest cyberprotests in China.

After his death, Chinese social media users set to work sharing Li’s story. Their purpose was straightforward: They wanted not only to acknowledge the doctor’s attempts to raise awareness of the virus, but also to call out the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) for waiting to disclose vital public health information. Protestors demanding free speech on TikTok held signs quoting Li, who said in an interview, “A healthy society should not have just one voice.”

But almost immediately, many of the social media posts about Li’s whistleblowing disappeared from cyberspace.

The cyberprotest reached a peak when the CCP censored the magazine interview of another doctor, Ai Fen. As Central Wuhan Hospital’s emergency department director, she had faced hostility from her hospital superiors after sharing the original diagnostic report with Li and other medical colleagues.

Savvy cyberprotestors then found other ways to communicate their messages about Li and Ai. To avoid the CCP’s censorship, they wrote posts entirely in emojis and/or in other languages, such as in Pinyin, English, German, Japanese, and even Klingon, a language from Star Trek.

Around the same time, another story about Chinese doctors started to emerge in China’s cyberspace. And these posts differed in one key way: They no longer included a critique of the CCP. Instead, users posted on social media platforms such as Weibo, TikTok, and WeChat valorizing Li as a national hero and praising the “sacrifice” that he (and many other doctors and essential workers) made to combat the COVID-19 pandemic.

How should we understand this transformation of Li’s story—from one that critiques the CCP’s surveillance machine to one that embeds Li into a nationalistic tale of triumph over the pandemic?

There is some truth to this tale of triumph: The Chinese government has, indeed, been more effective than many other nations in controlling the spread of COVID-19.

As of March 10 this year, according to the World Health Organization, China had reported 658,103 confirmed cases and 8,067 deaths from the virus. By contrast, the U.S., with about a quarter of China’s total population, had reported 78,614,707 total cases and 953,133 deaths. (However, researchers warn actual case numbers—in both China and the U.S.—are likely far higher than reported.)

However, regardless of the relative success of the CCP’s zero-COVID policy, as anthropologists, we think it’s important to dig deeper. We want to understand some of the political motivations and impacts of the Chinese government’s pandemic response.

Take, for example, the new digital technologies developed alongside China’s pandemic control efforts: Every citizen’s movements are now tracked through a QR code designed to monitor their health condition. They must scan the code every time they board an airplane or travel between provinces, and sometimes even when they enter shopping malls or take public transportation. Scholars warn these pandemic-era surveillance measures may easily be used as a tool for the CCP to tighten control over citizens even post-pandemic.

In addition to these overt changes in how public health is managed, the CCP has used the pandemic to assert their power over public discourse—and that’s where Li’s story comes in.

While in the U.S. public discussions about COVID-19 have revealed and reinforced some deep-seated political divisions, in China, stories about COVID-19 have become a uniting force. Many Chinese citizens now cite the United States’ mishandling of the pandemic to prove the superiority of the party leadership—and even to defend the one-party political system.

So, how and why have so many Chinese citizens come to praise the state leadership’s effective public health measures?

To answer this question, with funding from the Arthur Levitt Public Affairs Center at Hamilton College, we interviewed 20 citizens to get their perspectives on the different versions of Li’s story. During the interviews, we showed participants two TikTok videos about Dr. Li’s stories and asked our interviewees to comment on what they saw.

In browsing the videos about Li that first emerged in late February 2020 and are still circulating on popular social media platforms today, we noticed a few hashtags: #goChina, #goWuhan, #COVID, and #Dr.LiWenliang. There’s also one hashtag that might be less familiar to those outside of China: #spreadpositiveenergy. The phrase “positive energy” (in Mandarin, zhengnengliang, 正能量) repeatedly came up in our interviews too.

Where does this concept come from, and what does it mean?

The concept of positive energy took a circuitous route to become one of the most used catchphrases of the Chinese Communist Party today. Strangely enough, it was popularized as the translated title of British psychologist Richard Wiseman’s popular self-help book Rip It Up. Since 2013, positive energy has been taken up by the party leader Xi Jinping and is now routinely used in political rhetoric offering ideological “guidance” for citizens.

But while Wiseman’s book focuses on bringing out individuals’ inner potential, hopes, and motivation to improve the self, in the party’s ideological campaign, positive energy has become associated with the public good, and ultimately, the potential of the Chinese nation.

At the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China in 2017, for instance, Xi reported that the party’s “ideological work” had resulted in a “wave of positive energy” in Chinese society. More recently, the official People’s Daily newspaper stressed the need for Chinese citizens to “sing the main theme, and strengthen positive energy” (唱响主旋律,壮大正能量). (The former is a well-known phrase denoting adherence to the party line.) In short, remaining positive—and avoiding critical or negative narratives—has come to be seen as key to realizing what Xi calls the “China dream,” or the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” on the global stage.

This push toward “positive energy” is also foundational in the Cyber Administration of China’s regulation of cyberspace: Since 2013, social media celebrities have jointly declared to “take on more social responsibility to spread positive energy” and to abide by principles such as “laws and regulations,” “socialist core values,” and “national interests.”

Given this context, it’s not surprising that ordinary citizens have also taken up the concept of positive energy to digest the sacrifice of doctors and other essential workers during the pandemic.

One piece of media we analyzed during our study was the state-produced documentary The Lockdown: One Month in Wuhan. In the documentary, a voiceover praises doctors’ “effort in safeguarding humanity from the virus” and says their actions will “always be remembered.” In one telling scene, a doctor who contracted the virus while treating patients is seen immediately returning to work. “The battle with the virus is heating up,” the doctor says. “And I cannot desert [the battleground].”

In addition to presenting the work of medical professionals and other essential workers as nationalist sacrifice, the documentary highlights the sacrifices ordinary Chinese citizens have made to “win” the war against the pandemic. These include the constraints the public faced under lockdown, when all shops were forced to shut down except those selling food or medicine. Private vehicles could not travel on roads unless they had special permission, and most public transport ceased. Later people were not allowed to leave their homes at all.

We found in our research that many people articulated a similar party line linking nationalist sacrifice with positive energy. In one interview, for instance, we showed participants a video about how doctors’ hair had turned gray from working in Wuhan. Juying, [1] [1] All names of interviewees have been changed to protect people’s privacy. a 69-year-old female Beijing resident, responded that this kind of video “spreads positive energy.”

After Li Wenliang’s death, Chinese cyberprotestors held signs with a quote from him: “A healthy society should not have just one voice.”

When discussing Li’s case, Juying told us, “Li Wenliang informed others about the spread of COVID-19 as a doctor, and this is why people think he is a hero.” Although she firmly stated that Li’s death should have been avoided, she also believed that he died because he did not protect himself well from the virus. Juying never mentioned the CCP’s suppression of Li’s initial warning in our discussion.

Some interviewees explained the videos themselves also produce positive energy—something desperately needed during a pandemic. Xuheng, a 20-year-old college student, told us that watching the videos on the doctors’ sacrifice could be tiring, but they also moved him and put his own situation into perspective. As he put it: “If [the doctors] are helping others and saving their lives, why can’t I also hang on a bit more? They are the light in my life [during COVID].”

For these citizens, Li’s death itself was not positive. Yet the sacrifice he—and other essential workers and ordinary Chinese citizens—have made are part of “spreading positive energy.”

That’s because words and actions that promote societal development produce positive energy, while those critical of society produce “negative energy”—a force the CCP needs eliminated.

Taken together, the CCP rhetoric teaches citizens to speak and act positively, both for the good of oneself and for the nation.

One interviewee strikingly summarized this sentiment. Weidong, a 50-year-old Beijing resident, repeated the phrase the “Chinese nation” (zhong hua min zu) more than 20 times in our 30-minute conversation. After watching the video about Wuhan doctors, he commented that China’s strong emphasis on the pandemic had allowed the nation to get past the COVID-19 era. Referencing a recent spike in cases in Europe at the time of the interview, Weidong said, “The rest of the world is not like China.”

As for the detention of Li, Weidong told us, “Dr. Li Wenliang’s action brought positive energy: It pushed the Chinese [public health] system to solve a problem.”

While we agree it’s important to acknowledge the Chinese government’s success in slowing down the spread of the virus, we also recognize how such rhetoric enforces the CCP’s nation-building project. In the face of a pandemic, citizens seem more willing to accept the government’s messaging to stay united as a nation.

That’s why we want to reclaim the original story about Li told by cyberprotestors. Though Chinese citizens have not entirely forgotten this earlier narrative, the political significance of his whistleblowing is fading after two years. We must remember that his death was not a heroic sacrifice for the nation: It was a senseless loss that might have been prevented. That distinction is vital for understanding the full political ramifications of the government’s pandemic response in the years to come.