Baltimore’s Toxic Legacies Have Reached a Breaking Point

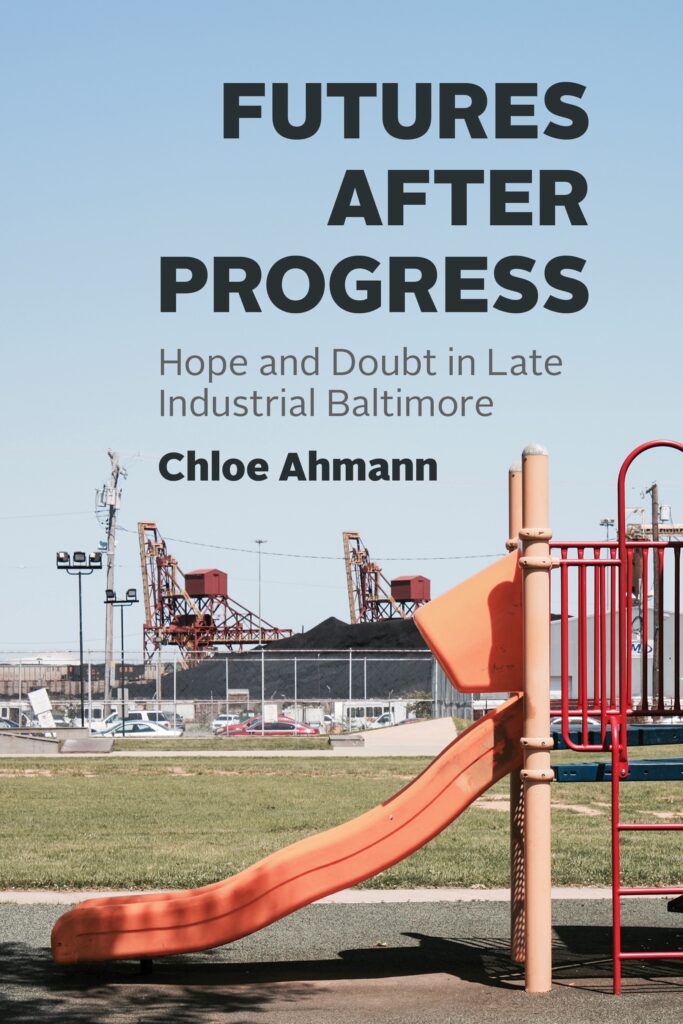

Excerpted with permission from Futures after Progress: Hope and Doubt in Late Industrial Baltimore by Chloe Ahmann. Published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2024. All rights reserved.

Last month, a 116,000-ton-capacity container ship departing from the Port of Baltimore veered off course and dealt a fatal blow to the Francis Scott Key Bridge, bringing down an icon. It was an astounding loss—not least for generations of working-class Baltimoreans whose livelihoods depend on port activity. While locals mourned the loss and divers combed the wreckage for the remains of six lost souls who had been working on the bridge when it collapsed, officials promised to help Baltimore get “back to normal.” It was an understandable response. It often is in the wake of a disaster. But normal is disastrous for folks on the bridge’s southwest side, where I’ve been working for just shy of 14 years.

In this part of the city, you’ll find a 14-million-ton-capacity open-air coal pier: the nation’s second largest. With the bridge collapse, that coal is waylaid with no place to go. So, piles grow. Already they loomed large before the accident. For decades, coal soot has mixed with airborne toxic matter from the many other smokestacks in this small community. That dark dust covers every surface. It coats cars and piles up on windowsills. It colors white rowhouses gray and turns the lungs of area crabs black. On summer days, it cooks into a noxious haze that makes it hard for little ones to breathe.

I used to teach first grade on this edge of the city, and 6-year-olds were the first to train my senses on the trouble in the air. Since leaving the classroom, I’ve studied the governing decisions that gradually produced these grim conditions—more, that made them “normal.” And I’ve followed locals laboring to build a better future from within the crucible of heavy industry.

The challenges they face are rarely as spectacular as the Key Bridge collapse, and in this excerpt from my new book, Futures after Progress: Hope and Doubt in Late Industrial Baltimore, I tell the story of one man who made a complex peace with everyday disasters. He worked in oil, not in coal, but lived “intimately” with both burdens. He conveys some of what it means to grow up in a place where the same forces that enable life also endanger it. If Baltimore gets “back to normal,” it will get back to more of this. “Normal” has made his hometown one of the most polluted places in the country. In my book, I trace what brought the city to this precipice, and I spotlight everyday folks calling for real change.

Bill and I connected long before we met in person. I got his phone number from a social worker at the local school who had met him one evening while canvassing. And though we made plans to get together many times, they usually fell apart: He had a doctor’s appointment, he felt too sick to go out, his medicine was acting up, his mother died, his sister died, he had to go get groceries.

Things were difficult for Bill, but it was clear he did not want to meet me in a wobbly condition, and even in our calls, he labored to contain the chaos of a life coming apart. Just days before I called for the first time, he was diagnosed with cancer. He told me it was “in the family.”

Cancer?

“No, just stuff,” he said, boxing up the topic of his health. Just stuff. The more we spoke, the more it seemed he meant toxicity.

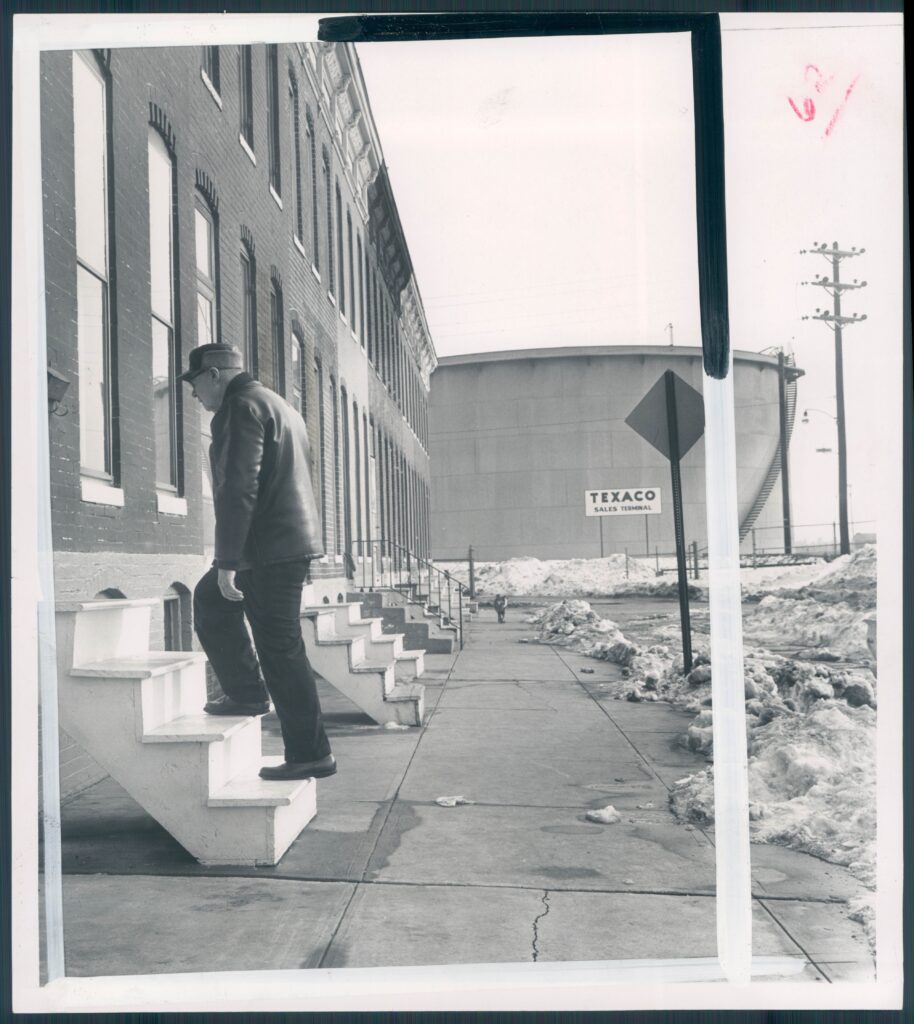

Bill did not like to talk about his illness, but he had a lot to say about the work that he thought caused it. For eight years before the company hired an “efficiency expert” and laid off most of its workers “overnight,” he held a union job at BP. Formerly known as British Petroleum, BP owned one of several oil terminals on the South Baltimore peninsula, which housed a spate of other high-risk operations. Before the oil job, Bill had made money digging graves on the peninsula. He told me graveyard work was a lot cleaner. But one morning in the 1970s, his dad—who had worked the terminal for 40 years—shook Bill awake to ask if he wanted “a real job.” Bill did. And so he landed at the yard around “that type of stuff. I was always around a chemical or two. Most people are but not as intimate as me.”

“A chemical or two” was one of Bill’s distinctive understatements. But if I were to set aside my reservations about fixating on the molecule and follow just one chemical through his tough life, that chemical would have to be benzene. Benzene is a colorless liquid found in crude oil and other substances that vaporizes fast and weighs down any air it enters. It also lets off a sweet aroma, but that gentle odor masks a vicious thing. The chemical is both highly flammable, giving it explosive potential, and slowly carcinogenic; even the American Petroleum Institute admits that there is no safe concentration. In addition to cancer, chronic exposure can cause bleeding and bone marrow problems, suppress the immune system, and impair fertility.

Despite these known effects, benzene is pervasive: in the 376 million gallons of gasoline that Americans consume each day and in the smoke emitted from our tailpipes, among other sources. When Bill worked in South Baltimore, benzene was also used to produce a whopping two-thirds of chemicals on record. Its toxicity was known then, too, but the boons outweighed the bad, apparently. It was, in fact, a fight over benzene regulations that led the Supreme Court to strike down “standards designed to create absolutely risk-free workplaces” if the cost of implementing them would be “unreasonably” high—not for workers but for industry.

So it was that Bill ended up being “intimate” with chemicals: “The yard men, we were right there with it. We climbed the tanks, mixed the diesels by hand.” That was fine, Bill shrugged, “you got used to it.” But other things were frightening. Like “when the [oil] ships came in, you might be working 30, 40 hours straight. And you’d be wore out, so you’d make mistakes.” Those mistakes could be disastrous. Bill still remembers one macabre scene.

Bill survived the accident (a gruesome fire following a tank explosion that lit up the summer sky) but received a grim prognosis decades later. And he was sure “that type of stuff” had killed his dad. “He died a terrible death,” Bill explained, years after he retired. “Tick, tick, BOOM. His heart exploded blood all over the pharmacy floor one New Year’s Eve.” Before Bill had not even realized his dad was sick. Or maybe he had—he wasn’t sure. In retrospect, his dad was always sick, but he didn’t like to talk about these things.

Bill guessed his father’s silence had to do with the value of a job back then, before the massive layoffs that had left Bill destitute. I guessed it was akin to Bill’s containments: The way he steered our talk past heavy stuff to keep composed. Both of us were right, I think. The choice to keep mum about some risks to reap the benefits of steady work—such decisions fill Bill’s spoken words. The desire not to look a problem in the eye—such gestures crowd his mundane memories. Of the way his mother kept a spotless home but stopped her cleaning at the threshold, letting dust consume the porch. Of the long showers Bill took after work to scrub away the sweet impurities. Of cracking crabs caught in the bay to find their lungs were black instead of white and taking care to eat around the edges. Of stopping at the little wooden box outside the bar where company men were asked to throw their greasy work clothes before coming in to drink.

People were always trying to keep “that type of stuff” contained, controlled, away, at bay, and still they had to mop the floorboards every day. These quiet disavowals thread through a life lived “intimate” with industry.

I did not want to see it then, as I listened to the disembodied voice of a man whom I had never met, but we were also intimates—bound by the gas that got me to and from this place, by the car exhaust that followed in my wake, by the question of who must stay and who leaves easily. I did not want to see it then: our material relations and our linked dissociations.

But it was there, and it is there: the sticky force of chemical complicity. [1] [1] The concept of “chemical complicity” comes from anthropologist Kali Rubaii’s virtual lecture, “Forensic Comparisons: War, Complicity, and Self-Confrontation,” delivered at Cornell University on February 2, 2022.