Reading the Future of an Amazonian Mine

Organizing a labor union is risky business. Even more so if you try to do it in an industrial mine in the middle of the Amazon. Katán, however, has no fear. [1] [1] All names have been changed to protect people’s privacy. Instead, he’s got shamanic knowledge.

He told me this one evening several years ago, shortly after he began collaborating in my field research. We were sitting in his wooden house close to the Zamora River in southeast Ecuador on the ancestral lands of the Shuar people—the country’s second-largest Indigenous group. Young, outspoken, and determined, Katán was keen to improve labor conditions at Mirador, the industrial copper-gold mine where he and many of his community members worked.

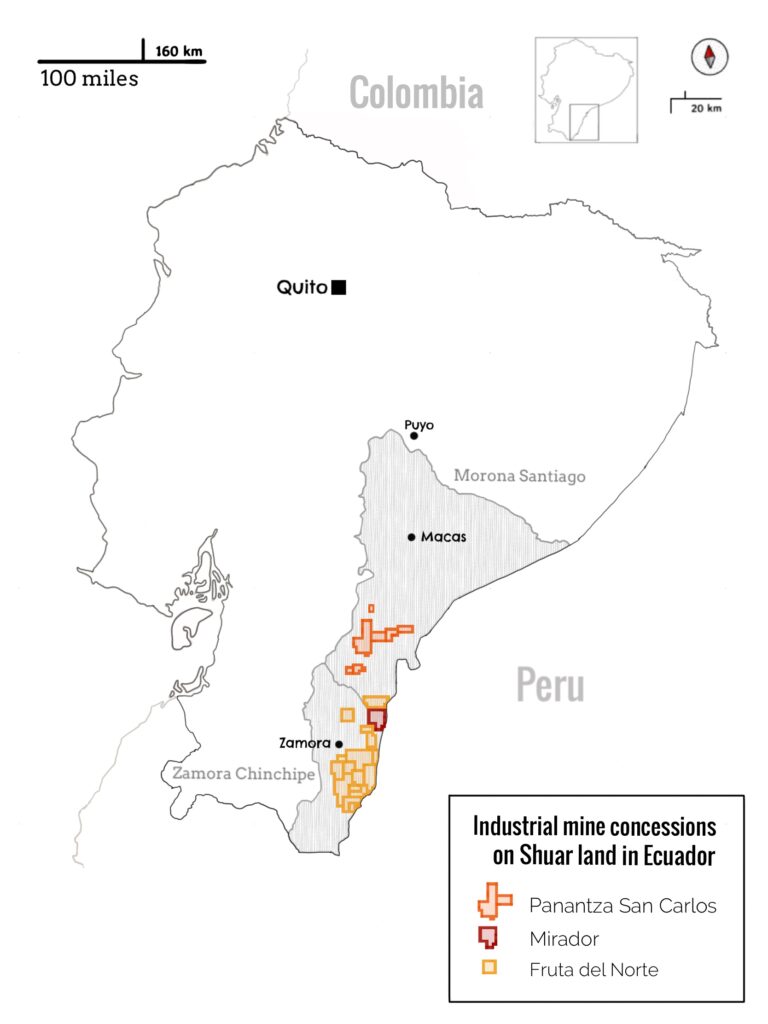

Foreign investors working with the Ecuadorean government started planning to extract minerals in the region on an industrial scale in the early 2000s. At first, some Shuar people were hopeful about the economic opportunities promised to them. Mirador opened in 2019 with great pomp as the first and largest industrial copper-gold mine in the country. Since then, most of the promises that investors and government leaders made have soured; very little economic growth is visible among Shuar communities. Recently, environmental organizations have warned about the possible risk of collapse of the mine’s two tailings dams, structures where the toxic byproducts of mining are contained. Other serious environmental concerns remain unanswered.

Mirador workers say that wages at the mine remain stagnant and work accidents are common. After years of struggle, they have been successful in forming a labor union to demand higher pay and long-term contracts with safer working conditions. However, the Chinese business consortium operating the mine has been able to bypass the union by exploiting a loophole in the law and outsourcing most of their workforce from small contractors.

Katán wants to change all that. If managers refuse to expand Mirador’s labor union, he wants to create labor unions for every small contractor involved in the project. He knows it’s a risky effort and is aware of the many union-busting tactics already in place.

But Katán also knows he will eventually succeed.

How does he know that? Through a dream induced by maikiúa, a powerful hallucinogenic plant known in English as angel’s trumpet.

Shuar people regularly turn to maikiúa and the hallucinogenic brew locally known as natem (or ayahuasca) to induce mettle, health, and vitality. But that’s not all. These plants create visionary experiences that allow Shuar people to predict the future—or, as some shamans say, “to know what will happen, how it will happen, and why things will happen.”

As a social anthropologist, I study how shamanic practices help Shuar people navigate both daily life and the urgent political challenges brought on by resource extraction. I’ve seen firsthand how large-scale mining dispossesses people of their homes and pollutes and deforests their ancestral lands. I’ve also had to navigate the sharp divisions that characterize Shuar politics. Shuar people do not always agree on the best path forward for upholding their territorial and political autonomy, and mining has exacerbated these divisions.

Despite these conflicts, Shuar do share a reliance on shamanic knowledge to help them make decisions and find the courage to navigate threats to their ways of life. Shamanic knowledge is thus shared by people struggling to improve labor conditions and by those fighting to put an end to mining altogether.

SHAMANIC PLANTS IN DAILY LIFE

The night of our interview, Amanda, Katán’s wife, placed a bowl of steaming boiled manioc in front of us and joined the conversation. Amanda agreed with her husband on the power of shamanic plants. Throughout her life, visionary predictions induced by these plants had not failed her once. It was natem, after all, who told her as a teenager that she would end up living with Katán in a southern region of Ecuador, far away from her mother’s land in Puyo.

But she also knew, from a different visionary dream, that however much she loved Katán, they wouldn’t stay together through their old age. “I saw another man,” she added, “standing next to me as I grow old.”

The twist taken by our conversation, delivered with astonishing casualness, left me dumbstruck. I turned toward Katán, but all I could sense in him was a mustered sneer of matter-of-fact resignation.

The courage and bravery that shamanic plants offer—succinctly captured by the Spanish word valor—are prized qualities within Shuar conceptions of personhood and leadership. Traditionally, Shuar people have associated visionary knowledge offered by these plants with personal growth, discipline, and finding or returning to one’s right path in life. In the past, when Shuar society was dominated by great warriors, gaining visionary knowledge was an important prerequisite to planning wars and retaliatory attacks against enemies and adversaries.

Nowadays, the insights revealed by visionary knowledge may become interwoven into people’s daily actions and long-term expectations of how their lives will unfold. They may turn to natem to decide whether to accept a job offer or pursue university studies, or, like Amanda, to reveal if the love of a partner will be permanent or fleeting. In troubled times, as anthropologists have documented, Shuar and other Indigenous Amazonian communities also turn to shamanic plants to gain determination and certainty when organizing and carrying out political action.

INDUSTRIAL MINING IN SHUAR AMAZONIA

Shuar people are famous for standing up for their sovereignty. The Spanish Empire that began colonizing Amazonia in the mid-16th century was never able to fully control Shuar territory. After a series of local revolts, the Spanish were forced out of the region in 1599. Shuar people would not be much bothered by outsiders for nearly 300 years.

In the 1960s, when the Ecuadorean republic expanded into their lands, Shuar people established the first Indigenous federation in Latin America. The Shuar Federation became fundamental in recovering Shuar land and defending its people from the invasion of settler colonists. Today the federation remains an important firewall between Shuar people and the Ecuadorean state and mining interests.

Still, over the past two decades, industrial mining has slowly and gradually changed daily life in Shuar territory. In the early 2000s, geologists, hydrologists, and archaeologists began hiring local people to survey and prospect the land. Lawyers and engineers followed, along with hopeful promises to local people of never-seen-before development, jobs, and economic growth.

By the time I arrived in Ecuador for fieldwork in 2015, however, the general mood throughout the region was acrimonious. A cloud of discord divided the communities affected by or dependent on mining. Some were still cautiously optimistic about what mining could bring to their communities. Others vehemently resisted any form of mine incursions, including the Shuar Federation and other nongovernmental organizations and activist groups. For instance, in 2016, Shuar demonstrators burned down a mining camp located on Indigenous land. But after finally failing to gain many supporters at Mirador, anti-mining protestors have mainly shifted to focus on the contested Panantza San Carlos mine, owned by the same business consortium that developed Mirador.

Over the years, anti-mining activists have faced violent consequences for their resistance. In 2014, José Isidro Tendetza Antún, a vocal critic of the industry, was found dead with signs of torture. His murder occurred just days before he was expected to travel to the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Lima, Peru, to denounce the pollution, deforestation, and eviction Mirador caused. Other activists opposing industrial mining report being frequently harassed, criminalized, and threatened by security staff and military personnel.

In short, though Shuar people do not agree on the best course of political action, no one is very happy with what large-scale mining has brought.

RESISTING FOR THE FUTURE

With the arrival of industrial mining, Shuar people have been forced to think about and reassess the futures of their communities and their lands. These are not uncommon demands faced by people whose livelihoods are increasingly threatened by resource extraction. But shamanic plant knowledge gives a unique power to Shuar people’s perceptions and approaches to these challenges. For Shuar people, holding visionary knowledge reinforces a sense of agency and confidence toward the future.

“Shuar, like other peoples in the world, can learn from our history and past experiences,” a shaman told me when I asked what it meant to know the future. “But only we can make history when we fulfill our visionary dreams.”

This sense of agency has accompanied Shuar people for centuries. Today it helps their communities reshape experiences of exclusion, exploitation, and colonial abuse into action. Those fighting to put an end to mining in their territories rely on visionary knowledge to confidently plan resistance actions, strategize on the best timing, and figure out who to trust. Likewise, shamanic plant knowledge informs those who, like Katán, fight from within the mining system to assert their autonomy and rights as workers in a mine.

To learn more about shamanic power and politics in Amazonia, listen to the SAPIENS podcast episode “The Conversion of Julio Tiwiram.”

A few months ago, I saw Katán and Amanda again. I was not surprised to learn they no longer lived together. As expected, Amanda saw the rupture of their relationship as the confirmation of her visionary experiences.

“What did I tell you? I saw myself aging with another man,” she told me. Despite the breakup, she was at peace and in no rush to settle down again.

Katán, on the other hand, had already found a new partner. After taking a long break to rebuild his personal life, he’d recently returned to work at the mine. Things had not improved at all, he complained. Two foreign workers had been crushed by a landslide and died the week before we met. He worried something similar could happen to people in his community.

“I came back just in time,” Katán said.

He then asked me to find the contact of a good labor rights lawyer in the capital. This time Katán was determined to follow through with his union-organizing plans. Nervous for him, I mentioned the possible dangers of bringing in a White lawyer from the city. He dismissed my worries. Hesitantly, I agreed to help.

Shuar individuals who have acquired visionary prowess are expected to be assertive, speak loudly, and thus step into prominence and leadership roles, especially as they pursue a given path. Katán certainly looked resolute, ready to accept his fate.

“Next time you visit, we should go drink natem with my uncle,” he said. “You’ll see that it will all be fine.”

TRANSCRIPT OF “BREWING NATEM” IN SPANISH AND SHUAR-CHICHAM

CRISTÓBAL NAIKIAI: Lo que yo digo al cortar es: “Natema iwiaitkiatá.”

“Umartajme.”

Entonces, la planta es un ser que a través de esto se presenta, se manifiesta en un ser supremo. Por suerte, si estamos nos revela lo que vamos a ser el día de mañana, a mí o a mi familia. Ya.

“Natema iwiaitkiatá.”

[Yaji] es una planta igual que natem, cumple sus funciones. Esto es lo que complementa los espíritus que el natem tiene, este le complementa. Eso le personifica, lo que allá no le completa. Esta planta, sí. Voy a coger un poquito más …

Esto hay que sacar a un lugarcito. … Ahí está en defenso. Ahí.

SEBASTIÁN VACAS-OLEAS: ¿Dejas arriba para que no molesten los animales?

CRISTÓBAL NAIKIAI: No; nada, nada. Ahí tiene que podrirse.

Voy a traer agua.

Ya está haciéndose espeso. Ya está haciéndose espeso.

Bueno, esta es la esencia de toda la preparación. Un bejuco largo que cortamos en varios pedazos, se hizo un buen montoncito, en la olla.

Cuatro veces he puesto agua que estaba hirviendo, y de eso salió esta esencia. Aquí está concentrado la vida, está toda la sabiduría de la selva, y los espíritus. Están aquí.

ENGLISH TRANSLATION

CRISTÓBAL NAIKIAI: This is what I say before chopping: “Natem, give me a vision to see.”

“I’m going to drink you.”

This plant is a being, and through this drink it will show itself; it will manifest as a supreme being. If we are lucky, it’ll reveal to us what we’ll be tomorrow, to me or to my family.

“Natem, give me a vision to see.”

This [yaji] is a plant just like natem; it has a purpose. It complements the spirits of natem. It personifies and provides what natem is lacking. This plant, yes. I’ll collect some more …

We have to take this some other place. … It is safe there. There.

SEBASTIÁN VACAS-OLEAS: Are you leaving it up there so animals don’t disturb it?

CRISTÓBAL NAIKIAI: Nothing should get to it. It should rot there.

I’ll fetch some water.

Look, it’s thickening. It’s thickening.

Here is the essence of all our brewing. It comes from a long liana that we chopped into several pieces. We piled it up inside a pot. I poured water four times into the pot to boil it until we got this essence. Life is condensed in here. It has all the wisdom of the forest and its spirits. They are all here.