Why I Talked to Pseudoarchaeologist Graham Hancock on Joe Rogan

ENTERING THE FRAY

I agreed to discuss archaeology with pseudoarchaeologist Graham Hancock on the mega-popular but controversial podcast the Joe Rogan Experience.

Celebrity author Hancock has made a fortune writing sensationalized books that claim a “lost” ice age civilization once existed—without any direct evidence for this society. I am an archaeologist, a scientist who uses the remains of objects, structures, and other traces of human activity to reconstruct how past peoples lived.

Some Rogan fans will surely dismiss my remarks as symptoms of a “woke mind virus,” which apparently infects anyone who relies on evidence, experts, and the scientific method to form conclusions. Meanwhile, some colleagues will call me foolish. A pawn playing into the hands of pseudoscientists.

Still, I’m appearing because Rogan’s podcast draws an audience in the tens of millions. If scholars want to curb the spread of misinformation, we need to stop just talking among ourselves or to audiences of like-minded people.

But reaching those outside my echo chamber demands more than my archaeological expertise. To approach engagements like the Joe Rogan Experience, I and other scholars must arm ourselves with science communication strategies, which research has shown can debunk misinformation in the current fake news environment. How I present evidence matters as much as what I present.

PLATFORM OR PLOY

After the release of Hancock’s 2022 Netflix series Ancient Apocalypse, archaeologists contested and condemned his claims through the forums of an open letter, news articles, op-eds, social media, and blog posts. Hancock invited a direct debate. In January 2023, Hancock and I agreed to sit down together on Rogan’s podcast.

The very next day I got a phone call: My cancer had returned. A PET scan, surgery, and a year of treatment followed. The podcast taping was indefinitely postponed. One popular pseudoarchaeologist, with over a million subscribers on social media, claimed I made up my cancer to avoid the Rogan episode.

Now more than one year later, it is happening. I’ve traveled to Rogan’s studio in Austin, Texas, to share real, scientific archaeology with a wide audience.

Rogan’s reach is enormous: According to a recent assessment, he boasts around 16 million YouTube subscribers, 19 million Instagram followers, and 15 million Spotify followers—three times the streaming service’s next-most popular podcast. Surveys have found these listeners or fans are over 70 percent male, are mostly between the ages of 18 and 34, and lean politically conservative.

I believe some listeners do have an interest in the past and will come with open minds.

But there are compelling reasons to avoid sharing soundwaves with science deniers. For example, physician and scientist Peter Hotez refused to appear on Rogan’s podcast with Robert F. Kennedy Jr., a vocal opponent of vaccines and third-party candidate in the 2024 U.S. presidential election. To Hotez, such a debate would seem to legitimize anti-vaccine views. (However, Rogan has interviewed many scientists on his podcast, including Dr. Hotez—just not at the same time as Kennedy.)

PSEUDOARCHAEOLOGY’S POPULARITY

I’m not debating vaccines. I’m distinguishing archaeology from mythology.

Pseudoarchaeology, or “alternative history,” draws major attention and casts itself as legitimate. Hancock’s books consistently rank as bestsellers on Amazon in the subcategory of “archaeology.” Ancient Apocalypse was one of Netflix’s most popular “docuseries.”

Beyond Hancock’s creations, Ancient Aliens dominates the History Channel. YouTube, TikTok, and other social media abound with archaeology-themed accounts describing giants, lizard people, mud floods, fake civilizations, and claims that the Roman Empire didn’t exist.

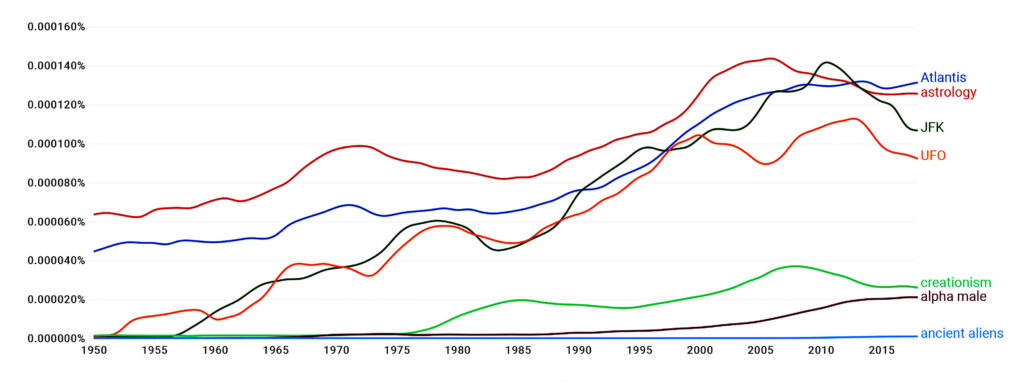

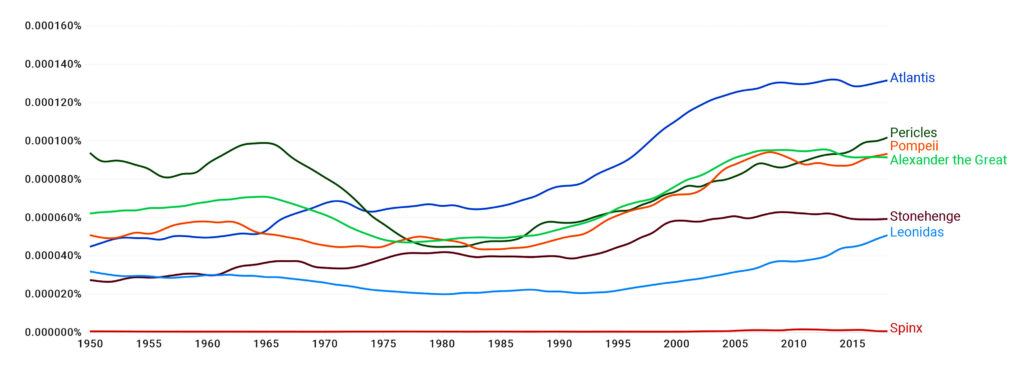

Many people buy it. Based on a recent survey by Chapman University scholars, nearly 50 percent of people in the U.S. believe in lost civilizations or ancient aliens. On Google Books Ngram Viewer, which counts words in English language books (not on social media), the mythical sunken city “Atlantis” ranks higher than terms related to other conspiracy theories, including “astrology,” “UFO,” “JFK,” “creationism,” “alpha male,” or “ancient aliens.” Atlantis is also mentioned more than the famous archaeological sites “Pompeii,” the “Sphinx,” and “Stonehenge,” and ancient historical figures such as “Alexander the Great.”

Meanwhile, it seems few people know what archaeologists actually do. K–12 schools in the U.S. rarely cover the field. Some universities are defunding and dismantling programs in archaeology, history, anthropology, art history, ancient languages, and classical studies.

DEBATING WHETHER TO APPEAR

I’m compelled to do something, which is why I agreed to go on the podcast. But I don’t enter Rogan’s studio naively.

A decade ago, science communicator Bill Nye publicly debated creationist Ken Ham. Some pundits called it a mistake. Ham used the spectacle to raise funds for his Creation Museum.

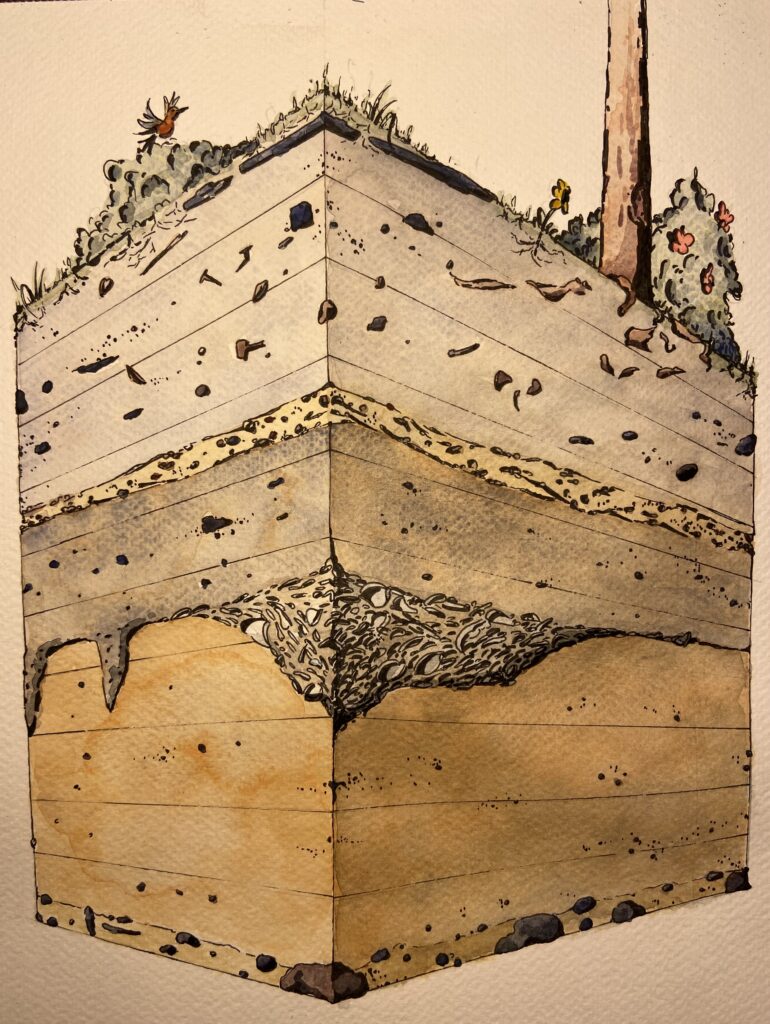

But in 2020—for the first time since polls began tracking people’s views on evolution—a majority in the U.S. accepted evolution, agreeing with the statement, “Human beings, as we know them today, developed from earlier species of animals.” For Gen Zers and millennials like me, the Nye-Ham debate provided real information in an accessible and entertaining way. I remember watching it and thinking about the power of stratigraphy—accumulated layers of soil and rock—for visualizing Earth’s deep history.

Now I face a similar dilemma. The podcast will generate buzz for Hancock and Rogan. But unlike Nye “the Science Guy,” a celebrity in his own right, the setting is flipped. The two personalities provide massive platforms: Previous Rogan podcast episodes with Hancock have had up to 27 million views. I’m a relatively unknown scholar who can share the cultural achievements of past people around the world.

SCIENCE-BASED STRATEGIES

My challenge: how to deal with the torrent of misinformation Hancock expresses. He purports all human history is explained by an Atlantis, a lost ice age civilization with advanced technology that was washed away by floodwaters. This single civilization built many ancient monuments around the world, according to Hancock.

Over the past 14 months, through the fog of cancer treatment, I’ve pondered how to argue a negative: the nonexistence of an alleged civilization. It’s easy to get bogged down in a Gish gallop—a barrage of fake “facts” and weak arguments hurled by an opponent. Debunking one pseudoscientific point after another, I would lose the chance to present a narrative of actual human achievements.

Recent misinformation research suggests a better approach, nicknamed a “truth sandwich.” Don’t start with a fake claim. Start with the truth. In the middle, you can address some fraudulent points. But top it off with another slice of truth.

Evidencing reality—what is known from archaeological and historical research—contradicts the lost ice age civilization.

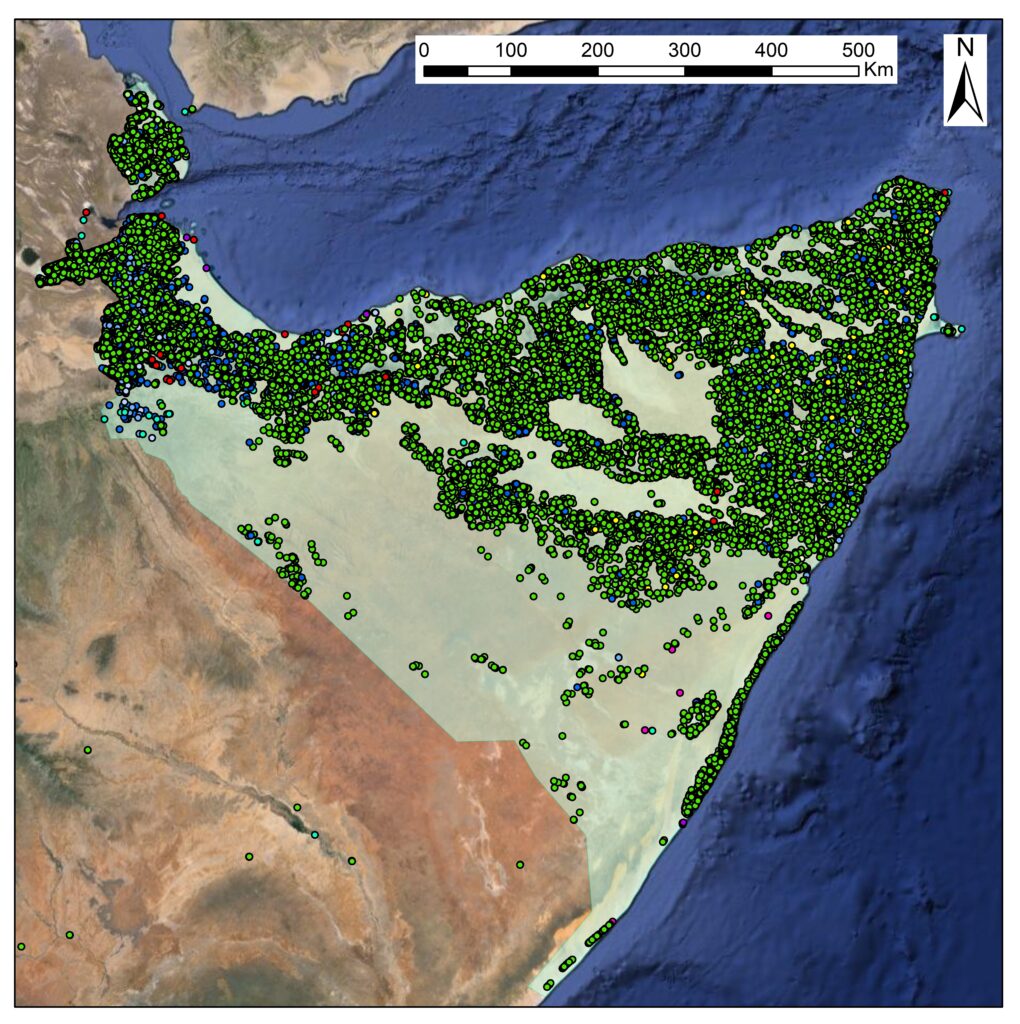

And that evidence for reality comes from millions of sites and billions of archaeological objects. Worldwide, ice age hunter-gatherers did build monuments: ones made from mammoth bones, enormous mounds of soil, and stone megaliths.

Archaeologists can even probe areas that might have flooded tens of thousands of years ago—potential locations for any drowned civilization. Movements of Earth’s crust have hoisted some ice age coastlands above the sea, allowing researchers to identify Stone Age sites in places such as southwestern Crete and islands west of mainland Canada. Underwater archaeologists also dive, find, and publish on under-sea Stone Age sites.

There’s no need to debunk every ephemeral “fingerprint” of the lost civilization Hancock raises. Instead, it’s about that truth sandwich. The reality presented from research on millions of sites worldwide leaves no room for a lost ice age civilization.

beautiful realities

This spectacle is not about winning an argument.

My goal is to share the magnitude and diversity of human achievement. Pseudoarchaeology robs Indigenous peoples of their heritage. Hancock’s narrative of engineering feats from some “lost” civilization includes the Sphinx in Africa, pyramids in Mesoamerica, and an enormous, terraced monument in Indonesia.

Does it include Stonehenge? No, Hancock says ancient British people built that.

Hancock and other pseudoarchaeologists center White Europeans as able creators while chalking up the accomplishments of other peoples to outside influences: the Atlantis civilization, aliens, lizard people, or the “lost” empire of Tartaria. Real archaeology inoculates people against the online and in-person racists who take Hancock’s polished presentation of a mysterious civilization and twist it into overt white supremacy.

I don’t expect to convince Hancock or his die-hard fans. But among the millions who may listen, some may be swayed—not by occult mystery but by beautiful realities of our human past.