The Dangers of Ancient Apocalypse’s Pseudoscience

This article was originally published at The Conversation and has been republished with Creative Commons.

NETFLIX’S ENORMOUSLY POPULAR new show, Ancient Apocalypse, is an all-out attack on archaeologists. As an archaeologist committed to public engagement who strongly believes in the relevance of studying ancient people, I feel a full-throated defense is necessary.

Author Graham Hancock is back, defending his well-trodden theory about an advanced global ice age civilization, which he connects in Ancient Apocalypse to the legend of Atlantis. His argument, as laid out in this show and in several books, is that this advanced civilization was destroyed in a cataclysmic flood.

The survivors of this advanced civilization, according to Hancock, introduced agriculture, architecture, astronomy, arts, maths, and the knowledge of “civilization” to “simple” hunter-gatherers. The reason little evidence exists, he says, is because it is under the sea or was destroyed by the cataclysm.

“Perhaps,” Hancock posits in the first episode, “the extremely defensive, arrogant, and patronizing attitude of mainstream academia is stopping us from considering that possibility.”

THE PSEUDOFISH DEFENSE

In the opening dialogue of Ancient Apocalypse, Hancock rejects being identified as an archaeologist or scientist. Instead, he calls himself a journalist who is “investigating human prehistory.” A canny choice, as the label “journalist” helps Hancock rebut being characterized as a “pseudoarchaeologist” or “pseudoscientist,” which, as he puts it himself in episode 4, would be like calling a dolphin a “pseudofish.”

From my perspective as an archaeologist, the show is surprisingly (or perhaps unsurprisingly) lacking in evidence to support Hancock’s theory of an advanced, global ice age civilization. The only site Hancock visits that actually dates to near the end of the ice age is Göbekli Tepe in modern Turkey.

Instead, Hancock visits several North American mound sites, pyramids in Mexico, and sites stretching from Malta to Indonesia, which he is convinced all help prove his theory. However, all of these sites have been published on in detail by archaeologists, and a plethora of evidence indicates they date thousands of years after the ice age.

Hancock argues that viewers should “not rely on the so-called experts,” implying they should rely on his narrative instead. His attacks against “mainstream archaeologists,” the “so-called experts” who “practice censorship,” are strident and frequent. After all, as he puts it in episode 6, “archaeologists have been wrong before, and they could be wrong again.”

Steph Halmhofer, a doctoral candidate at the University of Alberta who studies the use of pseudoarchaeology and erasure of Indigenous heritage by far-right groups, suggests that these attacks on archaeologists function to increase his sense of authority with viewers. As Halmhofer explains:

It’s about conspiracism and the positioning of Hancock as the victim of a conspiracy. The repeated disparaging remarks about archaeologists and other academics in every episode of Ancient Apocalypse is needed to remind the audience that the alternative past being proposed is true, regardless of the lack of conclusive evidence for it. And the vagueness of who this supposed advanced civilization was, combined with the credence given to it by being in a Netflix-produced series, is going to make Ancient Apocalypse an easily moldable source for anyone looking to fill in a fantasied mythical past.

DANGERS OF PSEUDOARCHAEOLOGY

In the last decade we have seen how conspiracy theories and distrust in experts impacts the world around us. And research has shown how pseudoarchaeology—especially when couched in anti-intellectual rhetoric—can overlap with more dangerous conspiracy thinking.

Of course, archaeologists frequently admit when we have been wrong. Any academic teaching Archaeology 101 or applying to fund a new study points out how new evidence updates our picture of the past. Despite the fact that every scientific field updates its thinking with new evidence, according to Hancock, any rewrites to history mean that archaeologists, his “so-called experts,” should not be relied upon.

Despite repeated claims made by Hancock, no archaeologists today see Stone Age hunter-gatherers or early farmers as “simple” or “primitive.” We see them as complex people. Priming viewers to distrust archaeologists also allows Hancock to use circular logic to re-date these sites.

THE MURKY ORIGINS OF HANCOCK’S THEORIES

Hancock claims in his book Magicians of the Gods that as the “implications” of his theories “have not yet been taken into account at all by historians and archaeologists, we are obliged to contemplate the possibility that everything we have been taught about the origins of civilization could be wrong.” However, archaeologists have repeatedly addressed his theories in academic publications, on TV, and in mainstream media.

Most glaring to scholars investigating the history of Hancock’s pseudoarchaeology is that while claiming to “overthrow the paradigm of history,” he doesn’t acknowledge that his overarching theory is not new.

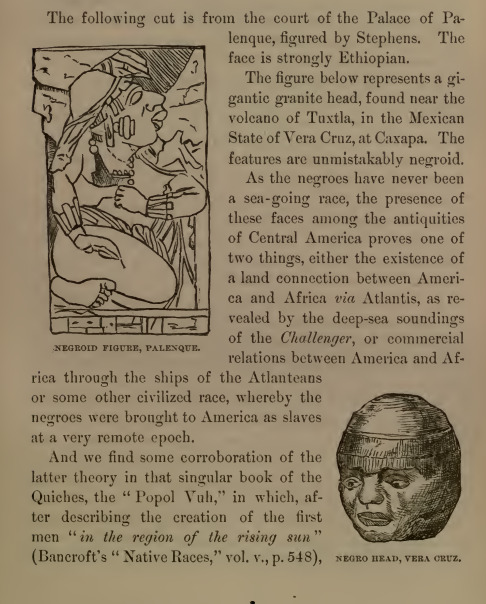

Scholars and journalists have pointed out that Hancock’s ideas recycle the long since discredited conclusions drawn by U.S. Congressman Ignatius Donnelly in his book Atlantis: The Antediluvian World, published in 1882.

Donnelly also believed in an advanced civilization—Atlantis—that was wiped out by a flood over 10,000 years ago. He claimed that the survivors taught Indigenous people the secrets of farming and monumental architecture.

Like many forms of pseudoarchaeology, these claims act to reinforce white supremacist ideas, stripping Indigenous people of their rich heritage and instead giving credit to aliens or White people.

Hancock even cites Donnelly directly in his 1995 book Fingerprints of the Gods, claiming: “The road system and the sophisticated architecture had been ‘ancient in the time of the Incas,’ but that both ‘were the work of White, auburn-haired men.’” While skin color is not brought up in Ancient Apocalypse, the repetition of the story of a “bearded” Quetzalcoatl (an ancient Mexican deity) parrots both Donnelly’s and Hancock’s own summary of a White and bearded Quetzalcoatl teaching Native people knowledge from this “lost civilization.”

Hancock’s mirroring of Donnelly’s race-focused “science” is seen more explicitly in his essay, “Mysterious Strangers: New Findings About the First Americans.” Like Donnelly, Hancock finds depictions of “Caucasoids” and “Negroids” in Indigenous art and (often mistranslated) mythology in the Americas, even drawing attention to some of the exact same sculptures as Donnelly.

This sort of “race science” is outdated and has long since been debunked, especially given the strong links between Atlantis and Aryans proposed by several Nazi “archaeologists.”

These are the reasons why archaeologists will continue to respond to Hancock. It isn’t that we “hate him,” as he claims, it is simply that we strongly believe he is wrong. His flawed thinking implies that Indigenous people do not deserve credit for their cultural heritage.

Netflix labels Ancient Apocalypse a docuseries. IMDB calls it a documentary. It’s neither. It’s an eight-part conspiracy theory that weaponizes dramatic rhetoric against scholars.