A Major Museum’s Attempt to Center Native American Voices

For decades, generations of families, elementary students, and tourists stood in the same dark, vast galleries of the Chicago-based Field Museum’s Native North America Hall. Under the yellow glow of spotlights, Native American and First Nations objects sat in glass cases, often grouped together by object types (axes, bowls, et cetera) or by culture area groups (Pacific Northwest, Southwest, et cetera). The placement and organization all depended on what the curator wanted to teach or show off to the visitor.

This is how Indigenous peoples of the U.S. and throughout the world have typically been represented in museums: White (usually male) “experts” have decided what was worth displaying of Native cultures and what was worth teaching, with the strengths and constraints of the museum’s collection in mind.

While there have always been exceptions, this dynamic only began to change in 1990 with the passing of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). [1] [1] Among others, these exceptions include Louis Shotridge, who was Tlingit and worked as an assistant curator at the Penn Museum in the early 1900s, and Arthur C. Parker, who was Seneca and served as an archaeologist and the director of the Rochester Museum of Arts & Sciences starting in the 1920s. This legislation finally required museums to return many remains of Native ancestors and sacred objects to tribes. More recently, efforts to decolonize museums have dovetailed with other activist movements such as Black Lives Matter, Idle No More, and Time’s Up that have challenged the ways historically oppressed communities are represented in public institutions.

It is in this context that Curator Emeritus of North American Anthropology Alaka Wali was finally able to gain support to redo the Field Museum’s Native North America Hall, which had largely been untouched since its installation in the 1950s.

As a fellow Chicago-based anthropologist who works in and researches museums, I met Wali in 2015. She and others at the Field had heard from Native peoples for decades that the gallery needed to change to reflect contemporary Native American identities and relations to the past. But the prospect of securing funding and creating a broadly representative consultative team was a tall order, requiring large-scale institutional investment in collaborative collections practices.

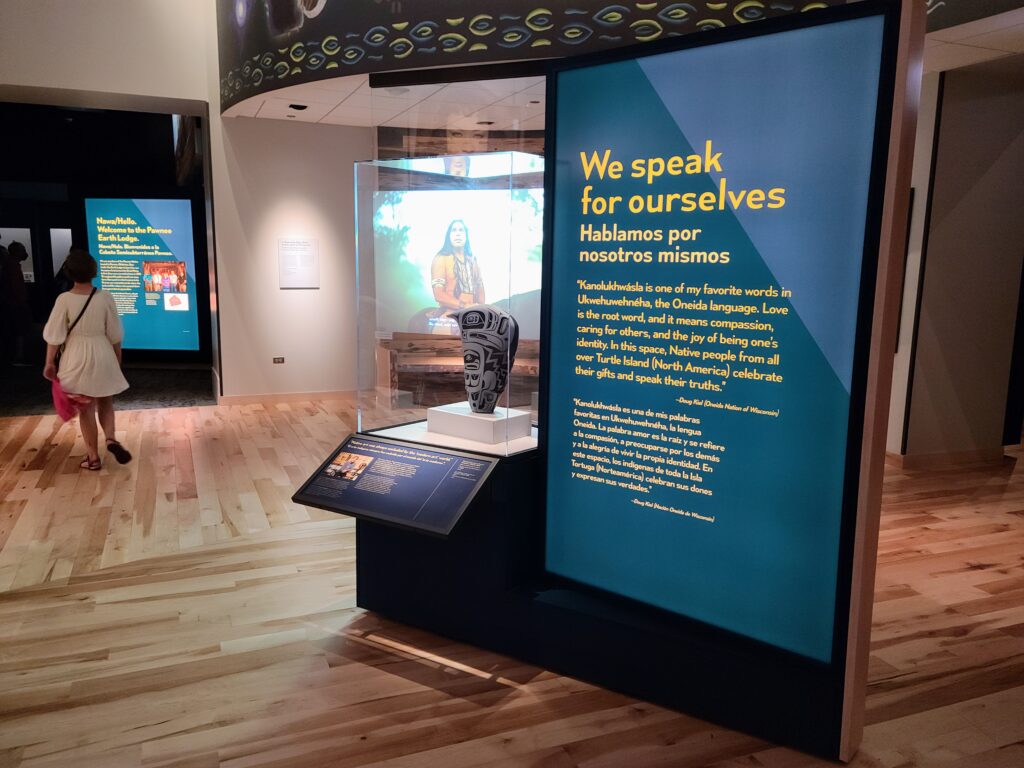

The result of this effort, Native Truths: Our Voices, Our Stories, is the Field Museum’s attempt to provide a platform for Native Americans to communicate their own identities and relationships with the objects in the museum’s collection. The goal is for communities to set the record straight—against all the ways they have been represented without consent.

TOURING THE EXHIBIT

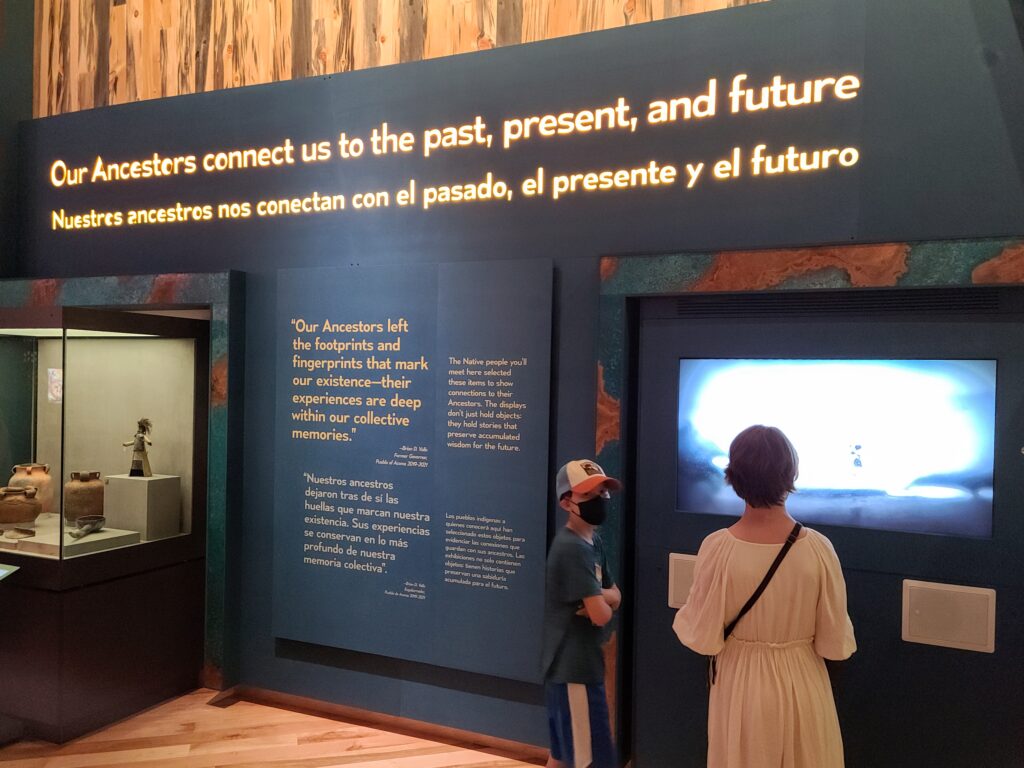

As the gallery’s new name suggests, the Field Museum’s redesigned exhibit aims to give “Voice” to Native communities to share their own “Stories” and thus their “Truths.” It does this by featuring the faces and words of several Native artists, elders, leaders, and scholars.

The exhibit itself is broken down into six primary rooms connected by hall spaces also filled with objects and content. Each of the rooms revolves around a specific practice or concept: the music of contemporary Sicangu Lakota hip-hop artist Frank Waln, the preservation of California basket weaving practices, the lives of Natives in Chicago, Pueblo architecture preservation, the traditional foodways of Meskwaki who live in Iowa, and a Pawnee Earth Lodge.

Visitors entering the first room are greeted with a Lakota language welcome text and a photo of Waln’s face. Waln’s explorations of contemporary hip-hop music establish that Native Americans today blend and fuse traditional and nontraditional cultures as they see fit. Visitors are even invited to combine Lakota and hip-hop musical elements into their own playable beat. The exhibition text throughout is in Waln’s voice as he describes the importance of the objects on display and communicates the meanings within his art. This portion of the exhibit is a powerful rebuttal to how Native Americans were represented previously in the objectifying glass cases, devoid of any presence of contemporary Native peoples.

Other exhibits are less innovative but nonetheless important in representing cultural and artisanal practices. In the basket-weaving room, practitioners demonstrate through written and video instructions how to make traditional California weavings. They also celebrate the importance of saving this knowledge from getting lost and the necessity of keeping the knowledge among their tribe through education. Similarly, Meskwaki agriculturalists reveal how food can bend time by bringing all generations of current and ancestral tribal members together in the moment of sharing culturally significant dishes.

The choices to highlight these specific practices emerged through extensive consultation and collaboration with an advisory committee and many Native American community members. [2] [2] To find out more, check out the forthcoming work of Stephanie Mach, a curator at the Peabody Museum at Harvard, who’s writing on the consultative processes at the Field Museum. As a result of these conversations, the exhibit not only features Native voices, but delves into high-stakes political issues involving Native communities, including repatriation, sovereignty, land-back initiatives, and environmental preservation.

WHOSE VOICES?

From my standpoint as a White academic, it seems as though the Field Museum’s Native Truths exhibit is an important step in the right direction for museums working in collaboration with Indigenous communities.

However, some questions lingered during my visit to the exhibit:

Who is the “our” of “Our Voices”?

When are Native collaborators speaking, and when are the curators of the exhibit speaking?

And who are they each speaking for?

The speaking subject of the Native Truths exhibit shifts frequently throughout. Sometimes the “we” is Waln’s Lakota community. Sometimes the “we” is Native Americans more broadly. Sometimes the “we,” especially in important self-reflective panels on NAGPRA, is the museum itself, which has not historically included many or any Native people on its staff.

These shifts in voice are not only contrary to the stated goals of the exhibit to center Native American experiences, but they are also visually confusing. Native Truths could have used distinctive colors or fonts for different voices, creating more of a sense of multiple individuals or communities in dialogue or even debate. Instead, the exhibit text collapses diverse Native American voices into a singular, visually monotonous “we.”

More dangerously, it collapses Native American voices with the museum/curatorial voice itself. By not indicating when the museum is speaking for itself versus when Native Americans are speaking for themselves, the exhibit seems to make “we” and “us” inclusive of both non-Native museum staff and their Native collaborators.

The effect is that the very same museum voice that has historically silenced Native voices and represented Native American identities and objects in old, racist ways—and without consent—is able to recast itself as a microphone of the oppressed instead of the voice of the oppressor.

TAKING RESPONSIBILITY

Native Truths has advanced what decolonization can look like in major American museums. The recentering of the exhibit to be by and for Native peoples is as impressive as it is heartwarming. The collaboration with and empowerment of Native communities in this exhibit is meticulously crafted by a staff who seems to truly care. Ultimately, however, curators and museum professionals are still responsible for ensuring Native voices are effectively implemented and clearly expressed through the medium of the museum.

If Native voices had been fully empowered to speak for themselves in the exhibit, as intended, they would clearly stand apart, and often against, a museum voice that has for centuries stolen the power to publicly represent Native identities. To elide this difference between voices feels as if the museum is hoping to benefit from an inclusive “new voice” without reckoning with its complicity in historic violences against Indigenous peoples. This fails standards of accountability necessary to foster real repair.

As a museum professional, I aim to add all the great collaborative strengths I see in Native Truths to my curation toolkit. But I also see opportunities to continue reflecting on how to equitably represent multiple voices—and reckon with historic injustices—in a way that best serves Native stakeholders.

Correction: September 25, 2023

An earlier version of this story incorrectly referenced the foodways of Meskwaki people in Michigan; the exhibit focuses on the Meskwaki Nation in Iowa.