Remembering the Woman Who Was My Second Mother in Cuba

When my cellphone rang on the morning of December 12, 2018, and I saw the call was from Paco Lopez in Miami, I took a deep breath. I told myself that he did sometimes call just to say hello or update me on the family in Cuba. There was no reason to expect the worst. But I knew that one day he’d phone me with bad news. This was the day.

“Se nos fue,” he said.

She was gone, I repeated to myself. Caro was gone.

Paco is the older of Caro’s twin sons. He began to cry, and I did too.

Caro, whose full name was Evangelista Caridad Martinez Castillo, had not lived quite as long as her father, who made it to 100, but she came close. She died at the age of 93.

When I was a little girl in Cuba, Caro was my nanny. She took care of me and my brother in the late 1950s, before our family left the island. What initially was a simple relationship of caretaker and child developed into something more complex and entangled, an intergenerational bond between a woman of the island and a woman of the Cuban diaspora. It emerged amid the social, economic, and cultural changes in Cuba that took place in the 1990s and that led to increasing contact and reconciliation between Cubans and Cuban-Americans. Caro became a second mother to me, an anchor to the island of my childhood.

What I visualize when I close my eyes now and imagine her are the quiet moments we shared in her house on lazy, warm afternoons, sitting side by side. We’d gaze at each other and try to see who we each had become after our lives were irrevocably changed by the Cuban revolution of 1959 that brought Fidel Castro and the bearded rebels to power, promising a utopian future for an island that had been ruled by dictators and controlled by the United States throughout the 20th century.

Caro breathed her last at home in Cuba, the island where she was born, the island she never left. She was cremated, and a few days later, her family scattered her ashes in the sea near her house in Havana. The ashes may even reach Miami, where Paco lives. He left Cuba in August 1996 and only returned once to see Caro and the rest of his family. He strove to put Cuba behind him, in the past, in order to move forward with his new life in the United States. Now he would live with the sadness that he wasn’t able to return to offer his mother a last goodbye.

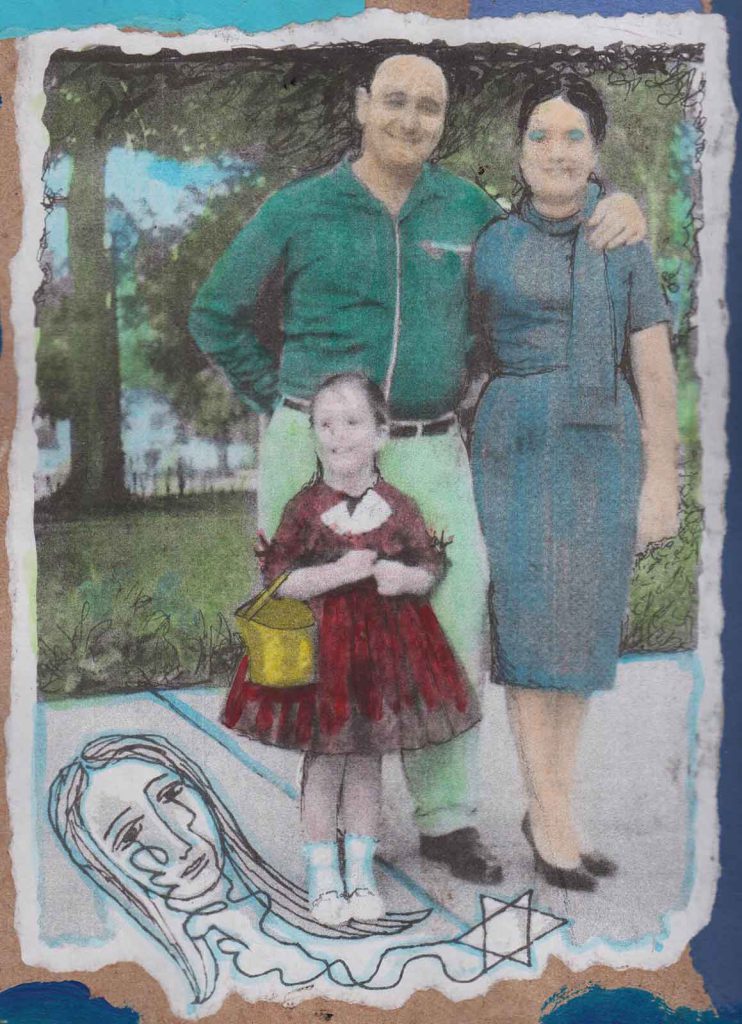

As my “nana,” Caro crowded in with us into the two-bedroom apartment that my newlywed parents rented in the Havana neighborhood of El Vedado. Caro slept in the bedroom with me and, later, my younger brother, Mori, and we all shared a small bathroom. (Racist taboos, such as those of the U.S. South that prevented black housemaids from sharing bathrooms with their white employers, were unheard of in Cuba.) The apartment had a balcony looking out toward the Patronato, the synagogue that was new then, built by the Jewish community that had found a welcoming home on the island and expected to remain in Cuba for generations.

Caro’s mother, a midwife, died when she was a young woman, and Caro decided to leave her countryside home of Melena del Sur, where her father and extended family struggled to survive doing farm work. It was 1957, and she sought out a new life in neon-lit Havana, a city of 1.3 million at the time. Few employment options were available to working-class Afro-Cuban women in the 1950s. She followed in the footsteps of her older sister, Tere, who was shy and serious, and learned Yiddish working as a nanny for my great-aunt and great-uncle. While they could afford to hire a cook and housecleaner, my father, who came from a poor Turkish-Jewish family, struggled to support us. But he found a way to hire Caro as a nanny and housemaid.

Though she worked hard, Caro did things her own way. My mother, Rebeca, whose Polish-Jewish family had been concerned about her marrying at the tender age of 20, was 10 years younger than Caro. She was uncertain of herself and let Caro run the household as she saw fit. She trusted Caro, and the two women, one Afro-Cuban, the other Jewish-Cuban, forged an unusual friendship, sharing stories and hopes. Whenever Caro returned to Melena to visit her father, my mother always prepared a care package with tins of tuna and sardines, which he craved and couldn’t find in the countryside.

We didn’t know it at the time, but our family’s days in Cuba were coming to a close. At the end of the Bay of Pigs invasion in April 1961, Castro declared that the revolution would uphold communism and the island would align itself with the Soviet Union. Many in Cuba’s middle-class opposed this political shift and felt betrayed that the revolution they had fiercely supported wouldn’t be moving in a democratic direction. Businesses and properties were nationalized, banks came under the control of the state, and parochial and other private schools were closed to make way for a national educational system that sought to provide equal access to learning for all children. Private farms were turned into collectives, and a rationing system was instituted to make sure all acquired basic nutrition. Critics claimed this system was a way of sharing poverty rather than redistributing wealth.

Along with many white middle-class Cubans, the majority of the Jewish community were disaffected by these reforms and left Cuba as the changes were being enacted, my family included. My mother recalls how she couldn’t stop crying her last night in Cuba. But she took comfort in knowing that their rental apartment and all of their furniture and possessions would be passed on to Caro. Sadly, the government ended up evicting Caro, giving the apartment to a loyal revolutionary, and forcing her to pack up her things quickly and find another place to live.

We left Cuba in 1961, spending a year in Israel, then arriving in New York in 1962. Throughout those years of turmoil and even long after, my mother and Caro stayed in touch by exchanging letters. My mother still has letters from Caro written on onionskin paper in blue ink and Palmer handwriting, folded inside airmail envelopes. In a letter from June 19, 1990, Caro writes, “All is well here, the twins are in high school, and Adriana [her daughter] is studying accounting. … I had to start working at my age [she was 65] because there’s nothing here. … I’m suffering from an ulcer and going through a dark moment in my life.”

My mother and Caro’s respect and affection for each other, and shared memories of the Cuba of their youth, became my pathway back to Caro. I first returned to Cuba in 1979 as a graduate student with a group of students and professors from Princeton University. We visited during the short-lived thaw in Cold War relations between Cuba and the U.S. under President Jimmy Carter. I found Caro, but our meeting was so brief it felt surreal.

After the fall of the former Soviet Union in 1991 and the loss of subsidies that had propped up the Cuban economy, the island fell into an economic depression and moral crisis. It was then that Cuban attitudes toward Cuban-Americans changed dramatically. We were no longer seen as gusanos, “worms of the revolution,” but as Cubans who lived abroad and shared a common heritage. Our remittances, visits, and cultural knowledge could be of assistance to the nation. In this era, the government opened the door to religion, allowing for freedom of religious expression and for Cubans to be members of the Communist Party and have a religious affiliation. Seeking to support this opening, the U.S. loosened its 30-year-long embargo, and many Americans began traveling to Cuba on religious humanitarian missions.

I felt a burning need to reconnect with the island—but my family disapproved of my going to the communist country that we’d fled. Against their wishes, I started traveling to Cuba in the early 1990s. At first, the experience overwhelmed me emotionally. I cried constantly and could only express myself in poetry. Only gradually did I find my bearings, working to create Bridges to Cuba, a forum for building literary and cultural bridges between Cubans on the island and in the diaspora, and carrying out anthropological research on the island’s Jewish community. But none of this work would have been possible if I hadn’t built a bridge back to Caro. She made me believe Cuba still belonged to me.

On my first trips back to Cuba, amid my emotional tears, I felt enthralled by the language, the culture, and the sheer delight of being on the tropical island where I’d spent the first years of my life. I felt great joy, but like all children of Cuban exiles, I’d grown up hearing what a paradise Cuba had been before the revolution and had been taught to fear the new regime. “Don’t talk about politics or you might end up in jail,” my family would tell me before my trips. Because those who emigrated in the early revolutionary decades were harassed for abandoning the island, Cuban-Americans, even those of the younger generation born in the United States, harbor a widespread paranoia that they won’t be able to leave the island if they return.

I visited Caro on every trip I made, two or three times a year, to Cuba. Our time together was an essential part of my return journey. Caro became my anchor, just as she was the anchor for many in her neighborhood. Lonely neighbors whose families had left Cuba for Miami would come by for a meal; street peddlers stopped in to grab a glass of water and use the bathroom; friends wandered over to watch the telenovela. Her door stayed open from morning until night.

Thanks to her kindness, I slowly shed my fears and forgot my paranoia. At her home in Miramar, a Havana neighborhood of embassies and pretty houses reminiscent of Florida’s posh Coral Gables, where she lived in a dank basement apartment that gave her twins and daughter asthma, I found a home in Cuba. She always welcomed me and my husband and son. In Caro’s neighborhood, my son learned to play barefoot in the street, jumping in the puddles left by tropical storms.

Caro acted like a second mother to me in Cuba. She worried if I didn’t call her every morning. She felt responsible for me and wanted me to come over every day for dinner. If I couldn’t, she asked me to call and let her know if I had other plans.

As many mothers do, Caro bragged about me, telling neighbors about poems and stories I’d published in Cuban magazines and in handmade books. Before every departure, she’d ask me when I was coming back. When I was away, she gathered articles from the official newspaper, the Granma, about literary and artistic events she knew would interest me. The newspaper clippings were always waiting for me. Caro wanted me to know I had a life in Cuba, and she helped me reclaim it every time I returned.

In addition to spending many hours with Caro on every visit, I got to know Tere, Caro’s older sister, who lived upstairs but was always visiting downstairs. I spent time with Caro’s twin sons, Paco and Paquín, and daughter, Adriana, discussing life in Cuba, laughing at jokes, sharing meals, and watching as Caro’s two granddaughters and grandson grew, and when her great-grandson was born. I got to know Caro’s relatives in Melena, and for many years, I would bring back to Michigan rum bottles filled with the delicious honey from their hometown. I was with her family during the sad times too—when Paco left Cuba and when Paquín fell into a life of desperate alcoholism that led to his death in January 2017. Losing the younger of her twin sons devastated Caro, who had done everything she could to try to save Paquín.

My mother had told me Caro was a person I could trust completely. But I had not expected that she would be a memory-keeper of my family’s presence on the island. One night after she’d cooked dinner for everyone, as she always did, she disappeared into her bedroom and returned with a cardboard shoebox that held photographs of her children and grandchildren. In the same box were photographs, perfectly preserved, of my family.

As Caro held up passport-sized pictures, dating from the 1940s, of my great-grandparents, Hannah and Abraham, to the light, I felt my heart skip a beat, thinking of the effort it had taken for her to hold on to these souvenirs from our shared past. She’d saved the photographs through years of revolutionary change, taking them with her when she was forced to leave our old apartment in El Vedado, then when she went back to her hometown of Melena, and later after she moved again to Havana.

We had left Cuba, but the memory of my Jewish family on the island had remained intact in Caro’s hands.

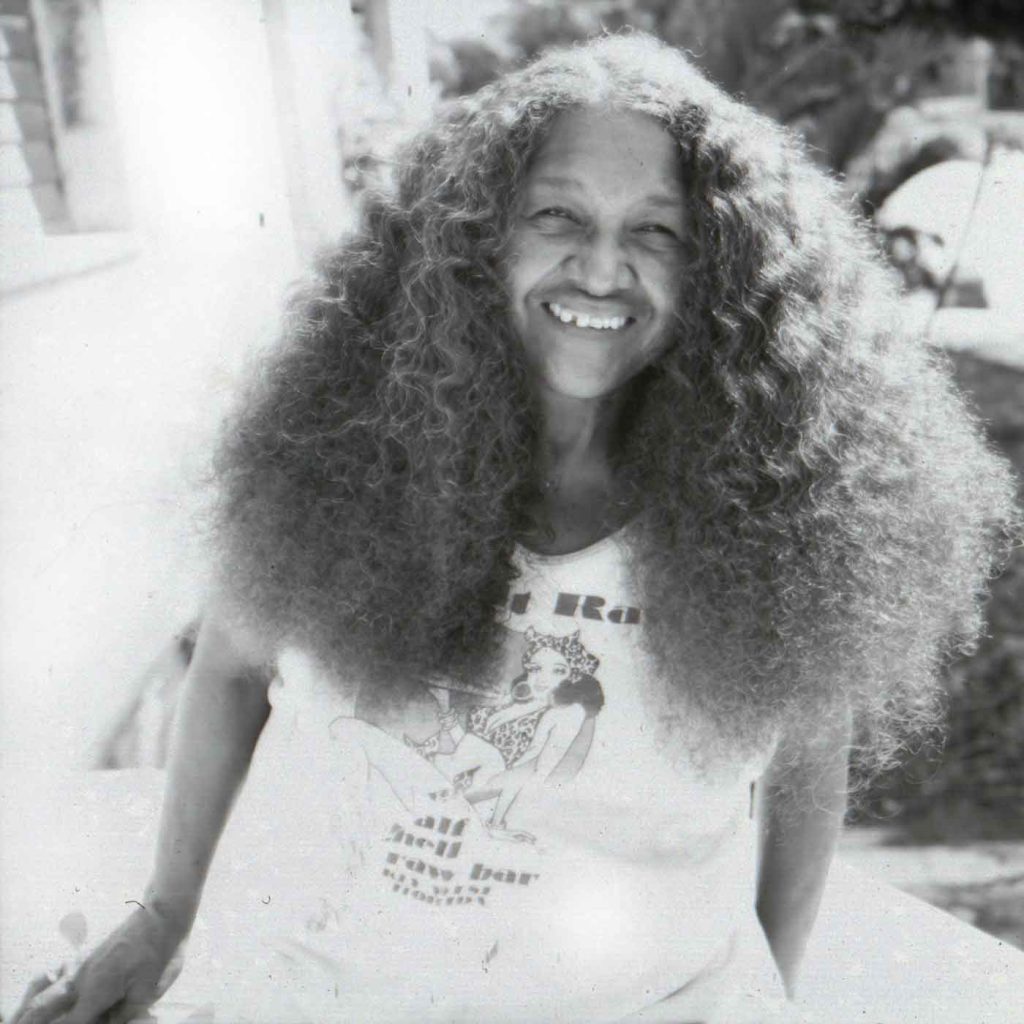

On a balmy afternoon when I was alone with Caro, during a peaceful stretch of time before she set about preparing dinner for the family, I got up the courage to ask if I could photograph her. She said yes, not in the least taken aback, as if she’d been expecting me to ask.

I remember looking at Caro in the waning light, marveling at the warmth and wisdom that emanated from her, the glow on her cheeks, the sparkle in her eyes, not a drop of makeup on her face. I tried to imagine how beautiful she must have been in her youth. But as a young woman, she did not possess the long hair she had as an older woman, and I thought, Here was a woman who had aged into an extraordinary sense of her own presence. She was a beautiful black woman, and I wanted to capture Caro’s beauty—a beauty unique to her.

When I later photographed her, I felt Caro let go of her burdens and allow herself moments of sensual pleasure as she fussed with her gorgeous hair, working out the knots and neatly dividing it into two braids. She seemed to enter a dream state when she did and undid her hair.

Photography became a way to gaze at each other across the distance between us as women of distinct historical eras and different racial and class backgrounds. Most of the time, we didn’t talk, but the silence didn’t feel uncomfortable. On the contrary, it was mellow, sweet, like a shared meditation. Caro didn’t pose or change her outfits for the camera. She presented herself as she was, wearing T-shirts and housedresses she’d received as gifts from the church down the street or from neighbors, friends, and me.

Retired from her government job, Caro spent her days scrounging for the best food she could find at the local bodega and farmers markets. Her meals took me back to forgotten memories of my childhood. She made an exquisite malanga purée, which is the first solid food given to Cuban babies. The comforting taste of this earthy taro root left me with a visceral memory of my lost childhood and made me feel I still belonged to Cuba and Cuba still belonged to me.

While photographing Caro in the plant-lined corridor outside her house, she told me how government programs set up after the revolution gave her an opportunity to study. She completed her education through the 9th grade, she said, and had wanted to go on and become a schoolteacher. But she had left her husband because of his drinking and had to take care of her three children on her own, so she found work as an office assistant. Her job, she told me, was to prepare stencils with statistical information, and she’d make coffee for her fellow workers.

Caro didn’t blame the revolution for failing to lift her into the life she had dreamed for herself. It was she who had fallen in love with the wrong man, she explained, and afterward, she’d given up on marriage altogether and returned to Havana to live with a friend.

Back when it was dangerous to attend church in the atheist heyday of the revolutionary 1960s, Caro told me, she secretly baptized her three children. She claimed not to believe in Regla de Ocha, the religion popularly known as Santería, a fusion of Catholicism and Yoruba beliefs brought by slaves from West Africa. But one day I saw her make an offering of a large clump of green bananas to the deity Changó on behalf of Paquín’s health. She told me her mother had been a spiritist, and Caro often left glasses of water out for the spirits (a Cuban custom even my Jewish mother brought with her to New York). Caro’s beliefs were an eclectic mix of religious traditions and self-fashioned oaths. Shortly before her death, she told me she’d let her hair grow long for Paco; she’d cut it when he returned to Cuba and give a braid to each of her two granddaughters, the one living with her and the one living on her own.

Each time I returned, Caro asked about my family. She remembered everyone’s names, even those of my distant cousins. Most of all, she wanted to know about my mother.

“¿Y cómo está Rebeca?” Caro would ask. Then she’d go on to say that she hoped my mother would come see her because she knew she’d never be able to go to New York. She was rooted in the island, and the idea of traveling so far seemed inconceivable to her.

After close to a decade of my visits, Caro lost faith that my mother would return. “Yo no creo que tu mamá va a venir a Cuba,” she said. With that, she disappeared into her bedroom, as she’d done before to look for the shoebox filled with photographs. She came back with a plastic bag from her wardrobe.

Caro had safeguarded our family’s memories, rescuing lost things from the obscurity of time.

Caro passed the bag to me and said in a whisper, “Dale esto a tu mamá.”

Inside were two transparent lace nightgowns my mother had worn on her honeymoon in Varadero Beach. They were made from the lace my maternal grandparents sold in their lace shop on Calle Aguacate, a narrow street in La Habana Vieja, the oldest section of the city. My mother had left the nightgowns behind in our old apartment when our family fled with only one suitcase.

“Why did you save these nightgowns?” I asked in Spanish.

Caro said that she thought my mother would like to have them. She explained in Spanish, “I kept them for her, hoping she’d come one day, and I’d give them to her myself. But since I don’t think she’ll ever return, I’m giving them to you to give to her.”

Caro had safeguarded our family’s memories, rescuing lost things from the obscurity of time. This memory, however, was strikingly intimate.

A few weeks later, I presented the nightgowns to my mother one evening when we were alone. She cried when she saw them, still in the shape of her young woman’s body. But the strong emotions that rose to the surface were so overwhelming my mother told me to keep the nightgowns, to hold on to them for her. I, then, became the memory-keeper.

At one point, my mother confessed to me that she wanted to go to Cuba, but she knew that would be upsetting to my father, who saw himself as a political exile and declared he’d never return. To avoid disagreeing with him, my mother chose to travel vicariously to Cuba through me, sending Caro a range of gifts that she bought with the money she earned as a secretary—things like Chinese embroidered slippers, cushioned walking shoes, silky blouses, fluffy towels. Caro was always grateful to receive these presents because they symbolized the bond with my mother. But it dawned on me that while Caro gave my mother and me priceless gifts of our history, we gave her things we could buy with money.

Life became more complex in Cuba as the 1990s passed and the 2000s unfolded. The economic system inched toward capitalism as the government expanded tourism. After the retirement of Fidel Castro, more opportunities arose for private enterprise through reforms enacted by his brother Raul Castro, who ruled from 2008 to 2018. But not all Cubans had the education, the means, or the connections to work in tourism and private enterprise. A new racism surfaced too, excluding the majority of black Cubans from those expanding sectors. Government subsidies shrank to almost nothing, making it difficult for elders like Caro to find their way in a system that still professed to be communist, and offered free health care, but expected people to buy essential goods, including cooking oil and detergent, in the overpriced government stores that had originally been meant only for tourists.

Receiving remittances from family in the U.S. or elsewhere became crucial for everyday survival. Cubans joked that everybody on the island needed fe, which means faith in Spanish. Cubans used the word as an abbreviation, the letters “f” and “e” standing for “familia en el exterior.” Although Caro had her son Paco in Miami, he was having trouble making ends meet and couldn’t help out as much as he had hoped. I became Caro’s reliable “family in the exterior.”

Our spiritual kinship served us both well. I found the connection to the island I had yearned for, and she received some additional money and gifts from the United States that helped her keep her family afloat. Caro was the second mother who waited for me on the island while I was the second daughter who came and went like a butterfly moving between two homes.

Unlike the classic scenario where the black maid was seen as “one of the family,” I was the former “little white girl” who had grown up and been adopted into a black family in Cuba. This role came with obligations I was only too willing to accept. I had read about the emotional labor of African-American women who became domestic workers in the South before the civil rights movement. White women who employed these women to care for their homes and their children yearned for the workers’ affection, even as they underpaid and overworked them. I didn’t want my relationship with Caro to repeat that history. We both strove to find a way for our “untellable story” to be liberated from the stereotypes. Nevertheless, it was clear that I had the privilege to come and go to Cuba, while Caro lacked the means to go anywhere else.

In the early years of my visits, when Caro was in the fullness of health, she enjoyed traveling with me to Matanzas, a coastal city less than two hours east of Havana, sometimes bringing along her granddaughter Amanda. Caro had never set foot in that hub of poetry, art, and music, known as the “Athens of Cuba.” Excursions within the island, I learned, are a luxury for most Cubans, as much as traveling abroad. But if I took the bus, Caro wouldn’t go with me. Only if I hired a driver with a private car would she happily come along. She had suffered through hard times. With me, she wanted a taste of the comforts she had never known.

But Caro couldn’t be away from home for long. Only once did she stay overnight with me in Matanzas. We slept in the same bed, as we had when I was a child, and listening to her breathe throughout the night, I felt safe. But she felt the weight of caring for her family. Her children and grandchildren depended on her, and Caro did all she could to respond to their fierce need for her maternal love.

As the years passed, I couldn’t spend as much time with Caro as I had in the early 1990s. After two decades of return trips, I became a Cuba expert and was in demand to lead American groups interested in learning about Cuba’s Jewish community and the island’s art, literature, and culture. For three different semesters, I took students to Cuba. And I was often busy doing research, traveling around the island, and interviewing people, getting to know the different provinces that Caro herself didn’t have the means to visit.

I was growing wings in Cuba and felt guilty. Caro understood, but I knew she missed my longer visits with her and her family.

One night, just a few years ago, I was in her neighborhood taking a group of American visitors for dinner at a private restaurant a block from Caro’s house. I heard someone call me by my childhood name.

“¡Ruti!”

Caro’s granddaughter, Amanda, was milling around in front of Caro’s house getting fresh air. She asked if I was going to stop in and say hello to Caro.

I had not yet had a free moment apart from the group, which demanded that I be with them during every moment of their journey.

I told Amanda, “I’ll come back another day.”

I realized suddenly that I was drawing a line between the two halves of my life in Cuba. There was the half that moved around in the bubble of the air-conditioned Havanatur bus and took Americans to visit successful artists at their home galleries, to peek into the windows of the mansion on the hill that belonged to Hemingway, and to see the impeccably restored colonial plazas of La Habana Vieja. Then there was the half that knew too well how difficult everyday life was for Cubans like Caro who barely made do.

The contradictions of that moment haunted me as we sat down at the two long tables set aside for the group. The restaurant was packed with foreigners. We were served the requisite mojito cocktail and enormous portions of chicken, lobster, and fish. Caro would have been shocked at the quantities of food and at seeing so much of it go uneaten.

But I knew it wasn’t a matter of taking Caro to a posh restaurant, which I had done several times in the past. That wouldn’t make things right. That night, it became all too clear that I could move back and forth between the tourist world in Cuba and Caro’s world, but Caro only had her world. I was not merely “an old little girl” returning to Cuba to conjure my past on the island. I was now a privileged person in today’s Cuba, part of the new cultural elite.

At the end of the week, I finally had a few hours free to see Caro. Before I left my hotel, I grabbed a bright red apple from the breakfast buffet. Apples are hard to come by in Cuba, and Caro loved them.

“¡Una manzana!” Caro exclaimed when I gave it to her. Then she stashed it in the bottom of the bag with the other gifts I’d brought for her and her family. If she left the apple out in plain sight, it would be devoured by whoever found it first.

I knew what Caro would do: She’d save that apple and carefully divide it up at dinnertime so each member of her family could have an equal piece for dessert. And had I been there, she’d have offered me a slice as well.

As part of our closing ritual at the end of a visit, Caro would go with me to the airport in Havana for our last goodbye, just as she had done when I left Cuba as a child. We kept re-enacting the traumatic scene of my departure. As Caro grew old and frail, she no longer came with me to the airport, but I’d go say goodbye to her the day before leaving, always promising to return.

A few months ago, as I took what would turn out to be the last photographs of Caro, she was too weak to comb her hair. I knew the end was near.

Now it is March, and I am back in Cuba, visiting Caro’s daughter, Adriana; her granddaughter, Amanda; her great-grandson, Diego; and her grandson, Rogelio, who all continue to live in Caro’s house. It is strange not to find Caro here. The family is grieving. Adriana has grown too thin, Amanda is having health problems, and Rogelio has painted the walls of the house a dark shade of blue. Diego, only 7, often asks where his great-grandmother has gone, and they tell him she is resting on the point of a star. “En la punta de una estrella,” he tells me, his eyes lighting up. “Allí está,” that’s where she is.

Caro’s family has lost their beloved matriarch, and I have lost my anchor to the island. But my photographs of Caro will remain as documents of our efforts to create a new bond, despite our differences, as Caro slowly faded away with fearless and intense dignity. And I know that the souvenirs she so carefully salvaged from the wreckage of the past and gave to me with an open heart will continue to serve as a guide for my ongoing, and always fraught, journeys of return to my first home in the world.