Among Gun Rights Activists, Fears About Survival Reign

Last year, the U.S. witnessed more than 650 mass shootings. Racially motivated acts of vigilante justice and hate crimes are on the rise. Since October 2023, reports of anti-Jewish and anti-Muslim attacks have increased in major U.S. cities, in part provoked by the Israel-Hamas war. Armed protests and other acts of political violence are also escalating, as epitomized by the January 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol in 2021.

This extreme polarization points to a very real possibility: The upcoming presidential election in November may no longer be a proverbial battleground for votes. We in the U.S. are already at the frontlines of a protracted—and sometimes violent—fight over the past, present, and future of “America.” Abetting the growing civil strife are electoral campaigns that capitalize on fear-based rhetoric for votes, particularly over controversial issues such as stricter gun safety regulations.

Some U.S. leaders may think widespread political extremism cannot happen here—but nothing inherently protects Americans from such forces. As an Afghan American, I often encounter perceptions that radicalization and political instability in Afghanistan are intrinsic to Afghans or Middle Eastern “culture.” In fact, President Joe Biden explicitly expressed that assumption in his defense of the chaotic U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan and the country’s collapse to the Taliban in 2021. He described Afghanistan as “a country that has never once in its entire history been a united country and is made up—and I don’t mean this in a derogatory [way]—made up of different tribes who have never, ever, ever gotten along with one another.”

But the reason extremist organizations successfully recruit among the disenchanted is not because of a shared, unchanging cultural heritage among their members. It’s because they tap into a universal human need for safety, belonging, purpose, and order. Political scientist Barbara Walter tracks the phenomenon of rising anti-government violence in regions around the globe in her book How Civil Wars Start and How to Stop Them. Among the warning signs she describes is the development of a slow, simmering insurgency not unlike what we’re witnessing in the U.S.

As an anthropologist interested in warfare and its impact on human societies, I set out in 2021 to conduct a year of ethnographic research on gun activism and county militias in Virginia. In 2017, white supremacist violence had erupted at a “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville. Then, when Democrats won control of the Virginia state legislature in 2019, gun rights activism soared across the state. The Virginia Citizens Defense League (VCDL), a political action committee focused on protecting the right to bear arms, saw its membership jump from 8,000 to 24,000 members.

What I discovered from talking to militia members was an almost pathological preoccupation with fear and survival, heightened by electoral politics that render a vote an act of self-preservation rather than one of political choice. Many members’ unwavering support for the Second Amendment was driven not by an ideological support for guns, but primarily by a desire for belonging and shared purpose in a world they perceived as profoundly endangered.

That finding is critical for understanding the political landscape in the U.S. today—and points to why those of us in the U.S. should be deeply worried about the direction we’re headed as a country.

SELLING SURVIVAL

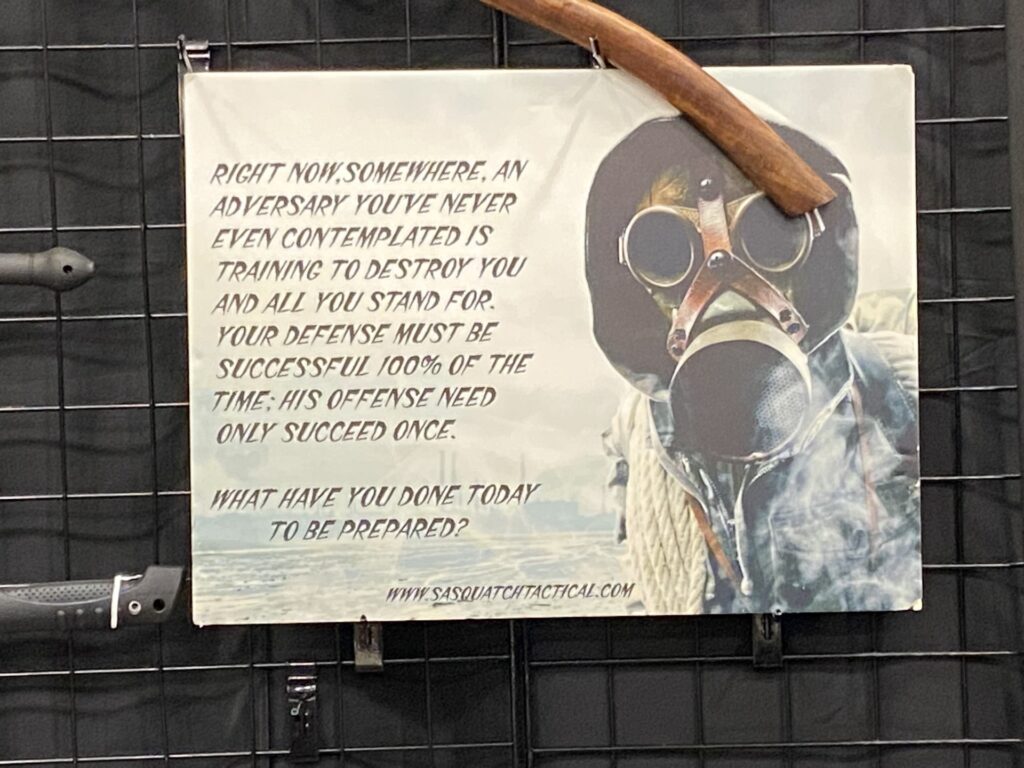

Guns aren’t the only thing on display at The Nation’s Gun Show. When I attended the show in northern Virginia in 2022, I was surprised at the ubiquity of survivalist supplies. I visited tables dedicated to organic agricultural subsistence and high-capacity water filtration, military-grade wilderness camping gear, hunting knives, and tomahawk axes. Sasquatch Tactical, a popular survivalist outfitter, stood among a crescent of interested attendees. A placard with an eerie picture of a head clad in a World War II–era gas mask blared an ominous message on the back display, ending with the line: “What have you done today to be prepared?”

Many Americans are practically terrorized into consumption. The interactions I experienced at the gun show strongly resonated with anthropologist Joseph Masco’s argument in his book The Theater of Operations. Masco writes of how the adversarial nature of the Cold War conditioned Americans to a pervasive sense of imminent risk and destruction. The ensuing mindset has allowed U.S. political power and the military-industrial complex to flourish side by side. The cultivated paranoia and distrust among smaller, local communities can be as readily mobilized by election campaigns as they can be by anti-government elements, foreign or domestic.

In reality, fears of the “other” America, on either side, stifle conversation and obscure common ground. My interviews with VCDL and other militia members revealed a far more nuanced picture of gun rights activism than I expected. While most of the militia members I interviewed supported or voted for conservative candidates, their views of gun control reflected more moderate ideals than Republican political rhetoric would suggest. Most supported proposed gun control ideas centered on extensive background and mental health checks, as well as significantly expanded training requirements for gun owners.

But there was one key difference with more moderate or liberal voters: Many militia members I interviewed expressed intense apprehension of tyrannical government overreach. They felt their constitutional rights were in immediate jeopardy.

Why was this constitutional right, as codified in the Second Amendment, so important to them? To answer that question, I had to dig into the deeper reasons people joined local militias.

ORGANIZING MILITIAS

Most of the militia members I met in Virginia were self-identified men of Western, Northern, and Eastern European heritage. Their impetus for starting or joining a militia was often sparked by a personal setback or tragedy. The impact of such events, ranging from joblessness to heartbreak or a death, often left the prospective members feeling alone, alienated, and/or in search of a purpose. Many of them found that sense of purpose in Second Amendment activism.

Most of the militia members with whom I spoke were moved to action by the narratives of politicians, particularly around election campaigns, who urged vigilance against the political seizure of guns and, metaphorically, of constitutional rights.

This should come as no surprise: The National Rifle Association spends about US$3 million annually on direct gun rights lobbying that supports pro-gun political advocacy. The trickle-down effect of such messaging appeals powerfully to people who perceive themselves and their communities as having lost status and being in decline.

But while I had assumed I’d find a consolidated, robust, and radical gun rights movement in Virginia, the groups I encountered were in constant flux. They gain momentum around election periods when candidates stoke fears of a progressive gun-grab. During such periods of heightened general anxieties, militias in Virginia will convene musters to attract new recruits. They offer training in the form of military “boot camp”–style workouts and skill-sharing sessions such as orienteering and shooting. But most of the time, the militias act as loose community engagement groups. The members I met volunteered for local relief operations, disaster management, or search and rescue efforts, often in conjunction with local sheriff, police, and fire departments.

I often wondered why more of the members had not joined the U.S. military. One of my interviewees, a Virginian in his late 20s who had started his own group, explained: “I didn’t join the military because I don’t like anyone telling me what to do.”

He recounted his path to the militia after a battle with drugs and depression. “I latched onto the Second Amendment sanctuary movement to pull myself out of that depressive funk,” he said. “I fell in love with fighting for rights.”

OPERATING WITHOUT NORMS

In Strangers in Their Own Land, sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild shares an account of Louisiana communities who physically and socially suffer from the conservative policies and politicians for whom they vote. Hochschild notes that the communities often vote against their own interests because politicians uphold the sort of liberalism they perceive to be an American norm, irrespective of how destructive it may be in their immediate lives. The constituents continue to support these politicians because their overall politics or policies speak to people’s sense of cultural identity, particularly at times when that identity and place in society appears to be vanishing.

Like Hochschild’s work, my findings resonated with a phenomenon sociologist Émile Durkheim describes as anomie—a social condition of normlessness. Absent what is familiar, such as social organization or shared values, solidarity in a society unravels, leading to upheaval and unrest. The COVID-19 pandemic, a resurgence of both white supremacy and civil rights movements, and a sharp economic decline in the U.S. have all deepened fissures along the seams of social cohesion.

Read more from the SAPIENS archives: “Without Norms, Societies Fall Apart.”

My interviews with militia members seemed to confirm this: Many felt that the country had evolved away from the traditional structures they often valued, such as religion and gender norms, and felt their “way of life” under attack by progressives. Most importantly, they felt invisible to and unheard by the very progressives who otherwise professed to uphold equality, representation, and tolerance.

It is one thing to feel an anomic tension, and another to have it reified by national leaders. Former President Donald Trump’s administration effectively leveraged the angst and anger so palpable among some American communities into a campaign victory—and the strategy might succeed yet again this year. While the tactic works, long-term consequences are dire.

With the next election on the horizon, U.S. leaders across the political spectrum need to understand and account for the top-down effects of their politically motivated rhetoric and superficial virtue-signaling disguised as legislative action. Words matter. Fear now proudly presides over the reconstruction of communities, relationships, and social values as the methodical architect of a new and genuinely terrifying national order.

The local militia groups I researched in Virginia lie on a crucial political fault line—one that looks increasingly unstable. The members are not insurgents by any measure. Yet they have the literal and figurative ammunition to become part of an insurgency if co-opted by the polarization that has consumed U.S. social and political discourse.

To restore America’s relationship to knowledge—and to one another—U.S. leaders must stop investing in weaponizing fear for political gain. Hanging in the balance is every stretch of America.