Prevention Through Deterrence: Picturing a U.S. Policy

Prevention Through Deterrence: Picturing a U.S. Policy

In September 2015, the disturbing image of a drowned Syrian toddler named Aylan Kurdi, whose body had washed ashore on a beach in Turkey, triggered an international outcry over the refugee crisis in Europe. In the heart of a bustling tourism industry, the Mediterranean coast lies in plain view of the public. The violence wrought by the Syrian Civil War, which intensified in 2015, has brought the bikinied bodies of sunbathers into contact with both the living and dead bodies of migrants. This visible juxtaposition is shocking, and it has made the term “humanitarian crisis” visceral to many who might otherwise be oblivious to such suffering. Yet, those who work with migrants and refugees know that these brutal scenes of pain, agony, and death take place daily around the world.

In the 1980s, undocumented migrants attempting to cross the border from Mexico into the United States were a familiar sight. Texas residents could often see desperate people wading through the muddy waters of the Rio Grande (called the Río Bravo in Mexico) from neighboring Reynosa, Mexico, in broad daylight. This brazen practice eventually garnered sufficient media attention to pressure immigration officials and politicians to create a new enforcement strategy. In the 1990s, the U.S. Border Patrol implemented a strategy called Prevention Through Deterrence. Since its inception, this approach has redirected migrant routes into the most inhospitable sections of the border, deploying the perilous desert as a tool to prevent entry into the United States. Although this security paradigm has primarily been used at the U.S.‑Mexico border, in recent years U.S. political pressure and policies have effectively extended it far south to Mexico’s jungle frontier with Guatemala.

Prevention Through Deterrence relies on the use of hyper-security measures such as high fencing and hundreds of agents on the ground in unauthorized crossing areas around urban ports of entry. The logic is that “illegal traffic will be deterred, or forced over more hostile terrain, less suited for crossing and more suited for enforcement.” In practice, for the last 20 years, the strategy has funneled millions of migrants towards places such as the Sonoran Desert of Arizona. In that barren and unforgiving landscape, people seeking illegal entry walk for days while negotiating extreme weather conditions, venomous animals, and other dangers. Federal policymakers rely on “hostile” geographic conditions, rattlesnakes, and ultimately, the risk of dehydration and death to deter migrants, essentially outsourcing border enforcement to nature.

Much to the chagrin of federal officials, Prevention Through Deterrence has done little to stop migration. The policy has mainly succeeded in turning border crossing into a dangerous and violent journey that occurs out of public view. Since 2000, more than five million undocumented migrants have traversed the Arizona desert. The bodies of 2,908 people who have failed to survive this gauntlet have been recovered in Arizona in that same time period, although it’s widely believed that the actual number of migrants who have died en route is far higher.

Few non-migrants venture into the remote corners of the Arizona desert. Border crossers often stagger into the United States—dehydrated, exhausted, and ill—and die. There are no photojournalists present to document these tragedies. No one is there to be shocked.

Political pressure in Arizona over the last five years has led to an increase in U.S. border security measures. These include multiplying the number of agents on the ground, deporting people to places far from where they were apprehended, and charging migrants with illegal entry in federal court and then sentencing them to jail time in privately run detention facilities. Determined migrants have once again turned to the muddy stretch of the Río Bravo that separates northeast Mexico from Texas, where security measures are currently less intense than those in Arizona. People are now attempting to evade law enforcement checkpoints by crossing the border in depopulated areas, walking for days across the desolate ranchlands of south Texas. As a result, the Border Patrol sector known as the Rio Grande Valley—an area consisting of 19 counties and over 17,000 square miles—has become the busiest illicit-crossing corridor in the United States.

One major change today involves the migrants’ country of origin. In 2000, Mexican nationals made up approximately 98 percent of the 1.6 million people apprehended and deported along the United States’ southern border. At that time, Central Americans accounted for the other 2 percent. In 2014, according to the U.S. Border Patrol, people from Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador, and other countries south of Mexico made up 53 percent of the 479,371 undocumented migrants apprehended at the U.S.-Mexico border.

To reach the United States, this new influx of Central American migrants often ride the notorious Mexican freight trains collectively known as “La Bestia” (“The Beast”), unforgiving machines that have taken the limbs and lives of many hopeful migrants. The number of adults and kids who have died or gone missing on this new route between Mexico and Texas is uncertain, but one study places the estimate at 47,000 people between 2008 and 2014. The discovery of a slew of mass graves of unidentified bodies in the northern Mexican state of Tamaulipas and in various county cemeteries in south Texas over the last five years suggests that this region, at the end of the migrants’ route, is the new undocumented-migration killing fields.

For a brief moment in the summer of 2014, the American public and the media focused its gaze on the border between Texas and Mexico. Troubling photographs of unaccompanied children being arrested by U.S. Border Patrol agents and packed into overcrowded detention centers created the perception of a new humanitarian crisis. This highly visible influx of Central American migrants was the result of people seeking refuge from unfathomable levels of violence, corruption, and poverty in their home countries. The U.S. government responded by putting political pressure on the Mexican government to step up their immigration controls in order to stop migrants before they could reach Texas.

To formally address the problem, Mexico announced an initiative called “Plan Frontera Sur” (“Southern Border Plan”) in July 2014. The plan’s stated objectives are to bring control and order to the undocumented migration of Central Americans entering Mexico and to ensure the protection of their human rights while in transit to the United States. This program has led to a serious increase in the number of deportations of Central Americans carried out by the Mexican government. A 2015 article in the Christian Science Monitor reported that Mexican authorities apprehended 92,889 migrants between October 2014 and April 2015—almost a doubling over the same time period the previous year. The Mexican government has also placed dozens of temporary immigration checkpoints in the southern state of Chiapas alone, along with large permanent checkpoints and detention facilities. Southern Mexico is starting to look a lot like southern Arizona.

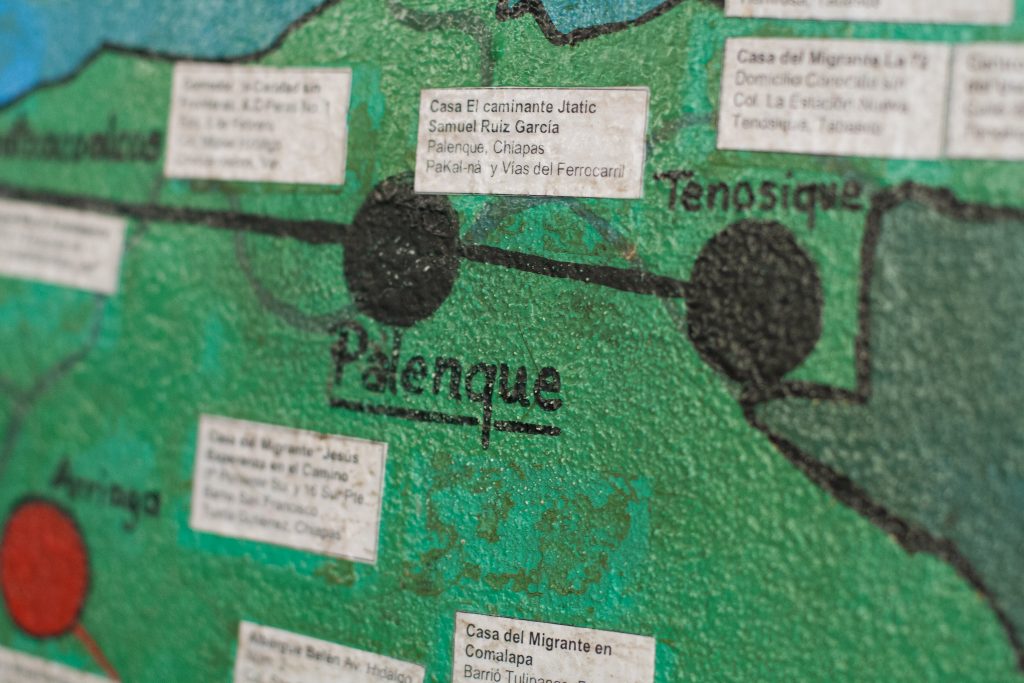

Building on research described in my 2015 book The Land of Open Graves, in the summer of 2015 I traveled to the sleepy town of Palenque in the state of Chiapas, a place mostly known for the ancient Maya archaeological site of the same name, to study the effects of U.S. political pressure on the lives of Central American migrants in Mexico. Palenque sits in the dense jungles just northwest of the Mexico-Guatemala border and has recently become a major thoroughfare for migrants entering Mexico from the south.

I was accompanied by a research team of 23 students and scholars from across North America associated with the Undocumented Migration Project, a long-term anthropological study of clandestine migration that I have directed since 2009. We witnessed firsthand the harassment and racial profiling of Central American migrants by local, state, and federal officials. We also saw the physical abuse that often occurs during raids on La Bestia. We interviewed hundreds of Central Americans who told stories of robbery, extortion, and assault at the hands of border enforcement agents and criminal organizations. These problems have only worsened in the wake of Plan Frontera Sur.

Migrants remarked to us that while it once took about 20 days to cross Mexico, it now takes weeks just to get out of Chiapas (if they’re lucky)—a direct result of having to navigate these new obstacles. Many of these people astutely noted that the shiny new deportation vans, combat boots, and stun guns being used by Mexican immigration officials were being underwritten by American dollars. Plan Frontera Sur is the newest iteration of Prevention Through Deterrence.

The following photos are snapshots of what Plan Frontera Sur looked like in the summer of 2015.