What It Means to be Human in an Asylum

“What It Means to be Human in an Asylum” is part of the collection Indigenizing What It Means to Be Human. Read the introduction to the collection here.

Gulabo ( گلابو)—Urdu for rose symbolizing love, courage, and passion

There are people who are immensely loved by everyone around them. [1] [1] The three women featured in these stories are composite characters based on women the author interviewed. Their laugh being contagious enough to cheer everybody around and sadness heavy enough to tear everybody down. She was one of them, loved for her warmth and resilience. Every day, she walked to and from the gate of the asylum, hoping to see her little brother. It had been seven months since he last came to visit her and left saying he would come soon. Clinging to his words, she got dressed daily, wore her favorite pink lipstick, set her pixie cut, smiled at the mirror, and walked restlessly as she waited for him. Not once did she take her eyes off the gate, saying, “What if he goes back without seeing me?” In a place where time was stagnant, it was only hope that kept her alive.

Questioning her worth, pleading for an answer, she held my hand firmly and asked me, “Was it my fault?” How could I make her believe: It was the fault of our ignorant society that only values a chaste woman. It was the fault of all the mothers who teach their daughters to suffer silently. It was the fault of the mindset that uses a woman’s virginity as a marker of her value. Above all, it was the fault of those five disgusting men who only viewed her as an object to satisfy their lust. How could I possibly make her believe, when, despite her being innocent, she was the one abandoned in an asylum while her rapists roamed freely on the streets, waiting to destroy yet another girl with dreams like hers.

Dreams so simple, like getting married and having a happy family, with a husband who would be infinitely loyal to her and six children, no less. She wanted a home filled with laughter and comfort. A home with a pink wall full of photo frames capturing the priceless moments. A well-loved garden with a family table, eight matching chairs, and her kids playing around. A board of Ludo lying on the garden table—teaming with the youngest child, Guddi, and engaging in a jolly banter with her husband as he chooses, in the game, her favorite color. Pots of sunflowers hanging next to a large window, blooming and smiling as the sun glimmers magnificently on them. A kitchen with a wooden stove to cook biryani and karahi just like her mother had once taught her. Plastic crockery with tiny red flowers on them to serve delicious anda paratha to her family in the morning. A home, enough to provide her family with the comfort and love that were now forever missing from her life. Such was her fantasy, so close yet so far—her dream, so simple yet unachievable.

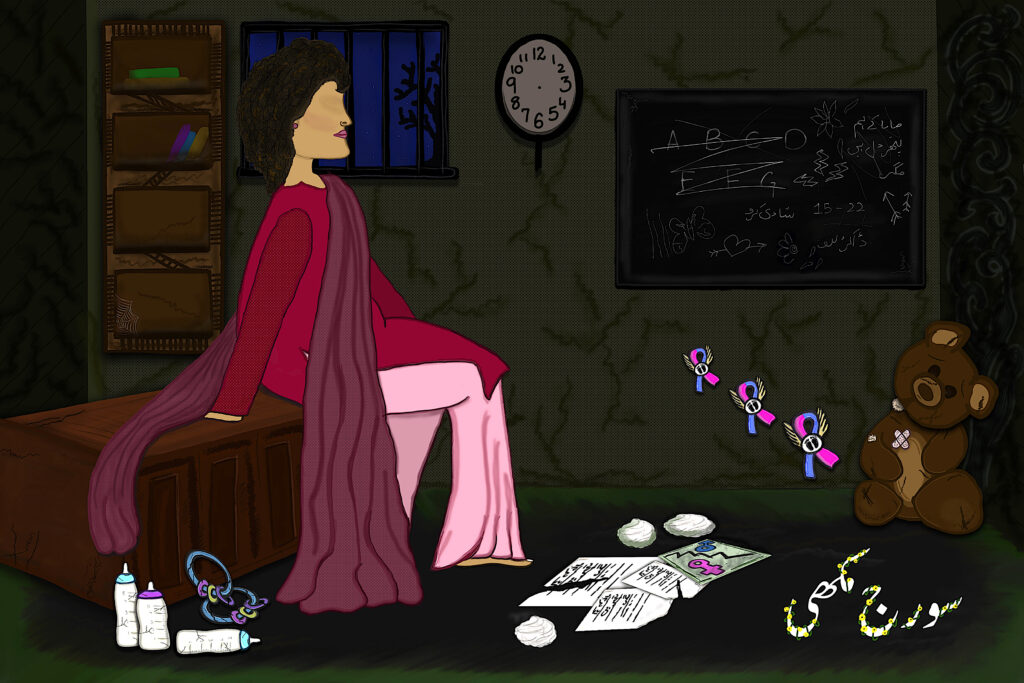

Sunflower (سورج مکھی)—Urdu for sunflower symbolizing warmth, loyalty, and devotion

Her smile as radiant as a sunflower, and her hair tangled like twisted figs. She was a nature child who took her chirpiness with her wherever she went. She was a giver of unconditional love and loyalty, and yet she had never experienced what it felt to be on the receiving end. She was a born nurturer, but her desire to raise children was dying with her dying spirits.

I ask you, where does all the love go when things go wrong? His name is still imprinted in her mehndi designs, and it shall remain in her heart forever. [2] [2] Mehndi is the art or practice of applying temporary henna tattoos, especially as part of a bride or groom’s preparations for a wedding. “It’s like my soul is intertwined with his soul,” she said, “and with every passing day, I crave his presence even more. But he didn’t look back, his ego was bigger than our love.”

She also experienced the trauma of losing her children, three in a row, after months of creating a haven for them inside her body. Both she and her husband lost children. The only difference was she was marked as a bearer of bad luck. Thrown in an asylum, she was left to grieve behind locked doors, away from him and his family.

If someone had asked her, she would have chosen to channel her grief into something meaningful. She wanted to keep her lost motherhood close to herself by being a teacher to orphans. To have a small classroom with olive green walls was her dream. Green reminded her of mother nature and the power of creation that it possessed. She, too, wanted to create a place of love where deprived kids could experience what it felt to be under a mother’s warmth. She imagined her classroom as a kaleidoscope of colors, where the kids could mess around with paints and leave their creative stains on walls. Calligraphed letters, fluttering butterflies, and blooming flowers all to be kept on the chalkboard showcasing the permanence of her love for these children. It would remind them every day that they matter and that they are and will always be treasured—unlike her. She longed for the love that was refused to her as a punishment for her beloved nature’s failure to give an heir to her husband.

Jasmine (چنبیلی)—Urdu word for jasmine symbolizing beauty, purity, and sensuality

Had she believed us: She was an angel disguised as a human. Pretty, like the lilac skies, with dark, heavenly eyes. But one could see the burden of expectations in her deep, teary eyes. What was holding her back? What was making her doubt herself? What was this angst that she was hiding?

Staring into the empty space, she questioned, “Can I ever be enough? Attractive enough to have a husband who will stay with me forever. Rich enough to not be thrown out of my brother’s house. Fair enough to have my husband value me. Slim enough to fit the size zero criteria. Tall enough to make every passing head turn. And lucky enough to not have been forsaken in an asylum.”

Her blood made her believe that she was low on the scale of beauty, and hence, not worthy of being wedded in a respectful manner. Her presence, a mere burden on the family. With every passing day, this destructive doubt was eating her away. Only if she could see that, in fact, she was enough. Brave enough to have survived what was meant to kill her. Kind enough to create a family out of what others call insanity. Enchanting enough to create a home of what is otherwise known as an asylum. Such was her strength that created a haven out of a hellhole.

In an alternate universe, she would have lived freely like a bird. Without any expectations tangling her to death. Without the fear of fitting the beauty standards set by the society. Without the dependency that made her weak and betrayal that left her alone. Carefree and cheerful like a bird. Content in her little nest curated out of her own strengths and abilities. Her safe den that would remind her that yes, she is enough. Enough to be loved, enough to be valued, and, mostly, enough for herself.