Dismantling the Walls in Our Heads

The German word for East is Ost. Straightforward enough, one might think. But in the once-divided country where I grew up, the word still carries geopolitical reverberations.

In November 1989, I watched the fall of the Berlin Wall on TV from my living room in upstate New York, open-mouthed. East Germans were streaming through checkpoints that had been hermetically closed to them for decades. People were dancing on top of the wall, which only that morning had still been part of the most draconian defense system of its time: the Iron Curtain.

Less than a year later, East and West Germany formally reunited. East Germans gained the right to travel and vote as they pleased. Since then, an entire generation has grown up in the reunited country.

And yet, the former border is still apparent in statistics on today’s society. Though Eastern Germans—those with roots in the former German Democratic Republic (GDR)—make up 20 percent of the total population, they occupy just over 4 percent of leadership positions in the economy, 8 percent in the media, and 2 percent in the judicial system. The divide also remains in the minds of many of today’s Germans—even, surprisingly, those who came of age after the fall of the Wall.

I grew up in West Germany, 200 miles from the border with the GDR. Without relatives there, I had little occasion to give those other Germans much thought. They only became real once the border was gone and I began to explore “the East” on visits to Germany. I was thrilled to roam in the footsteps of the protesters in the Peaceful Revolution and visit sites where composer Johann Sebastian Bach and poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe had lived and worked in their respective centuries.

My first inkling that the euphoria of 1989 was fading came in the form of language. I picked up on unfriendly nicknames Easterners and Westerners had devised for each other: Besserwessi (Western know-it-all) and Jammerossi (whining Easterner).

Another signal was the shifting political landscape, especially with the formation of the right-wing Alternative for Germany (AfD) party in 2013. Initially founded on an anti–European Union platform, the AfD has becoming increasingly nationalistic and anti-immigration. Though much of the AfD’s leadership hails from Western Germany, the party’s rise has been particularly strong in the East.

My occasional visits back to Germany, I realized, were not enough to understand what was going on. I had been doubly removed from life in “the East” by my West German provenance and, since 1987, my own life in the U.S.

Eventually, beginning in 2016, I decided to be an informal anthropologist in my home country and embark on an expedition to see for myself how the reunited Germans were doing. By bicycle and on foot, I followed the former border, which ran in an irregular zigzag line from the Baltic Sea to the border with what was then Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic), talking to people and observing daily life.

I learned that the Wende—a term that includes the fall of the Berlin Wall, the dissolution of the GDR, and Reunification—and the years that followed were a profoundly different experience for Germans in East and West. The process of integrating the GDR’s state-run economy with a capitalist market economy led to massive unemployment in the East and threw millions of lives into intense upheaval. Add to that the culture shock of relearning how to do everyday tasks, from renewing a driver’s license to buying a train ticket to applying for a job.

Few of the Westerners I spoke with seemed to be aware of any of this or know much about the people who lived just across the border. Many felt that things that had happened 30 years earlier surely no longer mattered now. Some mentioned how their tax money had been used to subsidize economic development in the East, including building new roads. Easterners, meanwhile, pointed out that the “solidarity tax” had been paid by all employed people, East and West.

Between the words and the stories, I often heard Easterners express a sense of aggrievement that their experiences and accomplishments were not respected. After all, they had brought down an oppressive government and then navigated profound disruption. Sociologist Steffen Mau coined the term “transformation fatigue” to capture the overwhelm many Easterners felt in the face of subsequent challenges, such as sweeping social reforms in 2010. Many felt Western-dominated media reduced their lives in the GDR to the Stasi (the GDR’s secret police) and a bankrupt economy—as if they had not had everyday lives, families, friends, or hobbies.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, even former chancellor Angela Merkel rarely spoke of her upbringing in the GDR. Only on her last Day of German Unity as chancellor in October 2021 did she share how dismissively journalists and commentators had depicted her pre-Wende life.

I heard misconceptions about Westerners, too, such as stereotypes that everyone in the West was wealthy, arrogant, or out for profit. At times, it felt like talking to people in parallel universes. I was reminded of Peter Schneider’s words in his novel, The Wall Jumper: “It will take us longer to tear down the Wall in our heads than any wrecking company will need for the Wall we can see.”

Schneider, one of the few West German authors who wrote about the Wall, penned this in 1982.

But there was more to learn. If I had set out on my expedition thinking that the divisions had surely been erased for the younger generation, I eventually became convinced otherwise.

My teachers in this process were a number of 30-something authors who call themselves Nachwendekinder—children of the post-Wende time. Though they never experienced life in the GDR, many of them have come to see themselves as distinctively ostdeutsch, or East German.

Journalist Valerie Schönian, born in 1990, examines this phenomenon in her 2020 book Ostbewusstsein. She only became aware of her East Germanness, she writes, through encounters with Westerners, such as the university student who summarized what she’d learned in school about the GDR as: “There once was an awful country. Thanks to us—the West Germans—the people there were saved. Now everything is fine.” The student had no understanding that courageous East German protesters had taken great risks to help bring down the Berlin Wall.

Author Johannes Nichelmann, born in 1989, also experienced GDR history in the reunited Germany as at most a marginal topic in school. The focus was West German history presented, simply, as German history.

I often heard Easterners express a sense of aggrievement. After all, they had brought down an oppressive government and then navigated profound disruption.

In a conversation with one Westerner, Schönian tried to convey the extent of post-Wende upheaval, the loss of an existential sense of security, and the condescension many felt from Westerners. When she suggested that such experiences might help explain how Eastern frustration could feed into support—or merely protest votes—for the AfD, the man responded that this was mere Ossi-whining.

The more I read and heard from Nachwende “children,” the more clearly I could see the many ways in which Eastern Germans are depicted as Others, as deviations from the Western norm.

But what about people who do not fit clear-cut categories of East or West?

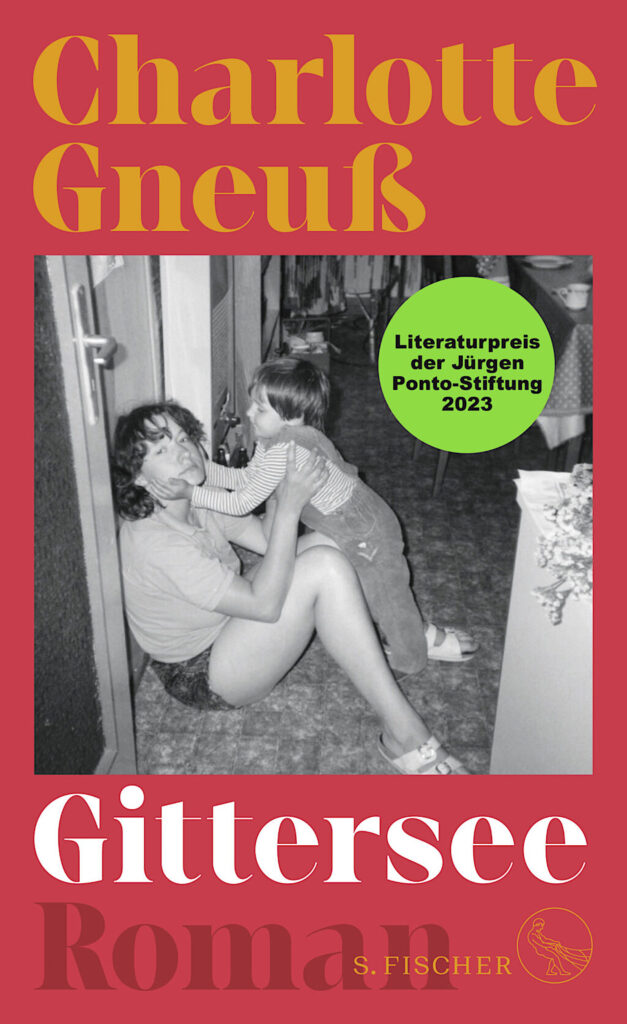

Charlotte Gneuss is a rising star in the German literary scene whose debut novel, Gittersee, was recently nominated for the German Book Prize. Set in 1970s East Germany and featuring a 16-year-old protagonist whose life is derailed by the Stasi, the book has since sparked a new Ost-West debate. Because Charlotte was born in the West, in 1992, some critics have questioned whether she has the right to write about life in the GDR.

However, “West German” is too simple a category to describe Gneuss. When I met her last year at a writer’s residency, I sensed after only a few moments of conversation a remarkable awareness of all things GDR and of the reverberations of its demise. I learned that her parents grew up in the GDR and that even as a child born after Reunification, she had been aware “that there was a different Germany from the one where I was growing up.”

Gneuss told me, “I’ve been commuting between these two worlds my whole life. And I sensed that my parents were happier and more self-confident in that other world.”

After her book came out, I asked her in an email how she felt about being slotted as a Western author by a major newspaper. “It is painful to be described as a West author when your own parents left the GDR for political reasons,” she replied. “And no, I am not an Ost author either. These categorization systems simply don’t work in this case.”

Like Schönian, she empathizes with the exasperation of many Easterners who feel their histories have been erased. “My parents were critical of the GDR government,” Gneuss told me. An attempt to “flee the republic”—a crime in the GDR—could have cost them the two children they already had. They applied for, and received, a rare exit visa in 1987.

The people in their new town had initially been welcoming. “At first my parents were something special,” she says.

But as large numbers of East Germans moved west after the Wende, these attitudes shifted. Gneuss’ mother, a nurse, once overheard colleagues referring to her as the “Eastern nurse,” who “can’t do the job as well.” This felt particularly arrogant because nurses in the GDR had more authority in the hospital hierarchy than those in the West.

Gneuss recalls that her parents were also haunted by their Saxon accents, whose nasal sound and half-swallowed words many Western Germans find grating. One holiday season, her mother had volunteered for a reading role in her church’s nativity play. She was told, “You speak ostdeutsch; that won’t work in the play.”

Like Schönian, too, Gneuss made clear that she does not see Eastern frustrations as a reason to support the AfD. But she does think it’s important to understand that the AfD and PEGIDA—a closely related anti-Muslim and anti-foreigner movement—aim explicitly at these frustrations by using slogans like “Wende 2.0,” implying that today’s Germany is just as repressive as the GDR was.

I asked Gneuss what she thought could be done to address the lingering frustrations. Without missing a beat, she replied, “A new hymn and a new constitution would be a good start.”

I was no longer surprised by her understanding of these historical details. What took place in 1990 was technically not a Reunification but the accession of East German territory to that covered by the constitution of West Germany. Legally, there had been another pathway, which would have required the writing of a new joint constitution. Whether it could have been done in the short window of opportunity is impossible to say now—the discussions in 1989–1990 took place under immense time pressure. But perhaps even now, 34 years later, a joint constitution could foster a greater sense of equal footing.

As for the hymn? Like the constitution and most aspects of public life, the West German national hymn became the hymn of the reunited country. But auspiciously, East Germany’s hymn used the same musical rhythm. If words really matter, the verses of the two hymns could easily be combined.

And words do matter, certainly for writers like Gneuss and the other Nachwende authors. In an interview, she said she wrote Gittersee “to find out how such a thing can happen—how a young girl can end up in the tentacles of the Stasi. And to reconstruct why my parents left the GDR—how a surveillance state can grow out of faith in something good.”

These young authors are anthropologists, too, I thought: They translate between worlds of meaning. Perhaps their books will inspire readers, in East and West, to enter these worlds. Perhaps some will even be inspired to undertake their own expeditions and have conversations with people they think of as Other. Perhaps eventually, we will tear down the walls in our heads.