Is Cyclical Time the Cure to Technology’s Ills?

The world changed dramatically on June 29, 2007. That’s the day when the iPhone first became available to the public.

In the 11 years since, more than 8.5 billion smartphones of all makes and models have been sold worldwide. Smartphone technology has allowed billions of people to enter and participate in a new, cybernetic, and ever more complex and rapid relationship with the world.

Humans have been tumbling headlong into this new digital frontier for a quarter century—since the World Wide Web went public. Until recently, that digital frontier followed Moore’s law, which states that computing power doubles every two years on average. With artificial intelligence, virtual reality, social media, and other mind-blowing developments, our technological world gets ever more interesting, changes ever faster, and, at least from my archaeological perspective, becomes ever more daunting. The rapidity of technological change, and by extension our current relationship to time, is undeniably unusual when viewed against the long evolutionary history of our species.

To illustrate what I mean, we can examine the rate of technological change across the epic sweep of humanity, from the moment we first appeared as a species in Africa until today. In so doing, we can gain a better understanding of the relationship between time, technology, and humans.

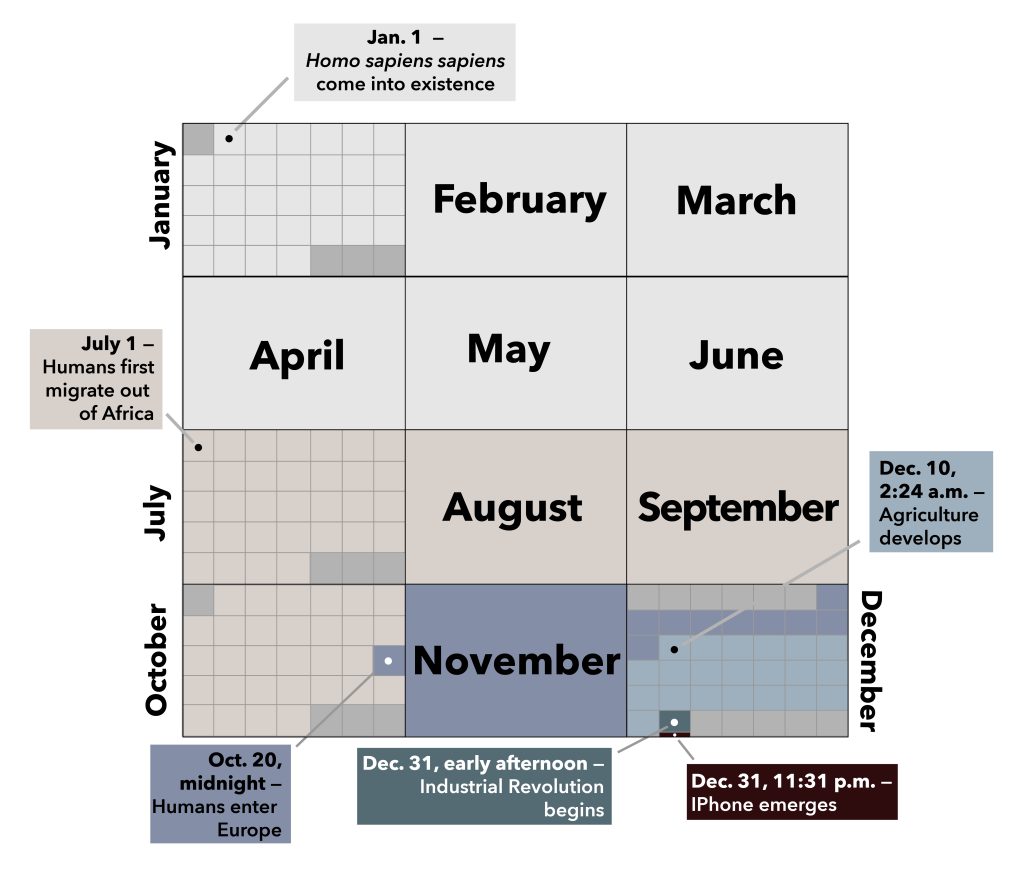

Our species, Homo sapiens sapiens, came into existence around 200,000 years ago.

(Recent discoveries may push the date of origin back to 300,000 years ago, but for the sake of argument, let’s stick to the well-established figure of 200,000 years. My point and the ramifications thereof remain unchanged.)

Two hundred thousand years is a long time, and it’s a hard number to fathom. So let’s convert that big, unfathomable number into something that we can all understand. How about a single calendar year?

To put 200,000 years of human evolution onto a calendar year scale, we first need to determine how long a real calendar year would be on that scale. Here’s how the math works: One year is 365 days; 365 days is 8,760 hours; 8,760 hours is 525,600 minutes; and 525,600 minutes is 31,536,000 seconds. When we divide 31,536,000 seconds by 200,000 years, we determine that a real calendar year passes by in 158 seconds, or two minutes and 38 seconds, on our scaled calendar year. A decade is over in 1,577 seconds, or 26 minutes and 47 seconds. A century is complete in four hours, 22 minutes, 48 seconds. And so on.

Now that we understand these numbers, we can put significant events in human history on our calendar year timeline. The first one is easy: Our species comes into existence in Africa 200,000 years ago, which is midnight on January 1.

Humans first migrated out of Africa 100,000 years ago—give or take—which is July 1 on our timeline. Let that sink in for a moment: For half of our existence as a species, we lived in, or very near, Africa.

Modern humans entered Europe about 40,000 years ago. That event occurs at midnight on October 20 of our calendar year timeline, when 80 percent of our species’ existence was already over.

Archaeologists agree that agriculture joins our technological repertoire about 12,000 years ago in the Middle East. That’s December 10 at 2:24 a.m. on our calendar year timeline.

The Industrial Revolution, a decades-long technological transition that ushers in, or at least makes possible, the modern era, occurs in the early afternoon hours of New Year’s Eve. Consider the implications of that fact: 99.9 percent of our species’ existence is over before we enter a technological context that is even remotely close to modern. But if you think about it, the Industrial Revolution is archaic compared to today! No plastics. No cars. No television. No radio. No telephones, much less smartphones. The Industrial Revolution marks the beginning of a remarkably different era for us as a species, yet it occurred during the last 0.1 percent of our time on this planet. Wow!

What about the iPhone? It shows up on our timeline at 11:31 p.m. on New Year’s Eve, within the last half-hour of our calendar year timeline.

It should now be clear that, when examined from this perspective, humankind’s relationship with technology, with change, and with time, is in uncharted territory. Rapid technological change is our new normal. Our ancestors—the people who preceded us for 99.9 percent of our species’ existence—would be terrified at the rapid rate of change we currently expect. It would be totally foreign to them. And, in some ways, it is still foreign to us too.

The question is, of course, what does it all mean?

I can think of three points worth emphasizing.

First, we should acknowledge that our current experience of time is unusual—it’s getting more and more precise and granular. Important events and overbooked schedules occur faster and faster with less and less chance for true relaxation.

Don’t you find it curious that we often say we don’t have enough time, even as technology gives us the ability to do more and more, faster and faster? It’s counterintuitive. Technology is supposed to make our lives easier and more pleasurable. As a result, we should have more leisure time, not less. But we don’t. We complain when a flight is an hour late, failing to marvel at the fact that we just flew 500 miles in an hour. It wasn’t so long ago—a century at most—that a 500-mile trip took weeks, if not months, and was potentially life threatening. Now we watch Netflix, drink Bloody Marys, and complain.

Second, we should recognize that the vast majority of people on Earth today believe time is linear, with one direction leading from past to present to future. But that’s a recent cultural construct. It’s important to note that for most of our species’ existence, humans understood time to be cyclical, with naturally recurring days, seasons, and years, all of which guided our behavior and activities. The archaeological record suggests that the Sumerians in what is now Iraq developed the first linear calendar about 5,000 years ago. That’s December 21st on our calendar year timeline!

Finally, it would seem that we are addicted to “new and improved” technology, perhaps for its own sake. There are many reasons for this, including capitalist product development schedules, marketing campaigns, and modern consumer psychology. The archaeological record, however, very clearly shows us that “old and just fine” worked sustainably well for the vast majority of our species’ existence.

What if we went back to celebrating the seasonal round for what it is: a natural, rhythmic context for our lives? What if we went back to honoring a cyclical “paleotime”? We already do it on vacation—we sleep when we’re tired and get up when we’re rested. And we’re noticeably happier as a result. Mind you, I am not advocating a chaotic system. Natural biorhythms exist, and humans typically adhere to reasonably predictable wake-sleep cycles.

I am, however, suggesting we return to a less precisely scheduled lifestyle than the one we currently have. The ever-increasing rate of technological change in our lives has led to slavish adherence to ever more refined and precise slices of time in our lives. Keep in mind that such temporal dominance and precision has occurred only in the last few hundred years (since the Industrial Revolution), a ridiculously small sliver of our species’ time on this planet.

I hear what you’re thinking: “My busy schedule would never allow such a change.” But that’s exactly my point—our overscheduled, hyperprecise, Western approach to time doesn’t allow us to stop and smell the roses, much less enjoy nature, think deeply, or learn a new hobby or skill. If these trends continue, as technological change gets faster and faster, the slices of time we experience will likely get smaller and smaller, our lives will be increasingly stressed, and the problem will get more acute. Where’s the breaking point?

Cyclical time, on the other hand, is more fluid and not susceptible to such time-crunching compaction. It is therefore amenable to a more relaxing way of life—one not dominated by technological change for its own sake. A return to cyclical time might just facilitate a return to a way of life for which our brains, hearts, and souls evolved over hundreds of thousands of years.

Speaking of which, I think it’s time for me to take a nap.