Can Digitizing Gravestones Save History?

DIGITIZING GRAVESTONES

One day last fall, when Kerri Klein was photographing gravestones at Burial Hill Cemetery in Plymouth, Massachusetts, a mother who is blind and her child approached her. They asked Klein if she could show them the monument to the General Arnold shipwreck, the majority of whose crew of more than 100 were killed in a storm in 1778.

As Klein led them to the memorial, she became aware of how narrow the paths are for a person walking with a cane. When they reached the obelisk, the child read the epitaph aloud while the mother felt the stone and traced the words with her fingers.

In this moment, Klein saw an opportunity for technology to help. “If you could 3D print a model of these stones to use in public outreach, it’s a tactile experience that really aids in learning by touching,” she told me. That’s just one idea Klein has for making the archaeology of the cemetery more accessible to everyone. After all, she says, “why do we do anything we do if other people don’t have access to it?”

Klein, a doctoral student in applied anthropology at the University of South Florida, is the founder of the Burial Hill 3D Digitization Project. Her mission is to photograph every one of the more than 2,300 gravestones on Burial Hill, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. She will then stitch together the 2D photographs to create highly detailed digital models and 3D prints—a process called photogrammetry. The heart of her project is to share archaeology with both experts and the general public, and to protect the cemetery’s unique cultural heritage.

I am an anthropology doctoral student working on Burial Hill as part of the Plymouth Colony Archaeological Survey, and I have known Klein since 2015. Since I learned about Klein’s project last year, I have felt very invested in and fascinated by her work. I spoke with her about the importance of digitizing gravestones, the rising popularity of photogrammetry in the age of COVID-19, and the ethical quandaries of documenting a place so directly connected with colonialism.

THE FRAUGHT HISTORY OF BURIAL HILL

For around 12,000 years, what is now called Burial Hill was home to the Wampanoag people and their ancestors. The Wampanoag built the village of Patuxet, with its domed houses (“wetu”), cornfields, and workshops to make stone tools. Between 1616 and 1619, a plague that had been transmitted by Europeans decimated Wampanoag communities across the region.

In 1620, the passengers of the Mayflower ship that had sailed from England to what is now Massachusetts established the Plymouth Colony at Patuxet. They built homes, a fort, and a palisade wall.

Burial Hill (originally “Old Fort Hill”) was turned into a burying ground in the last decades of the 1600s after colonists abandoned the original village and left for other newly established colonies. Many notable historical figures were laid to rest in this cemetery. These include Plymouth Colony Gov. William Bradford, activist-poet Mercy Otis Warren, and possibly Tisquantum, the last living Wampanoag from Patuxet, who taught the Mayflower passengers how to farm.

This deep history inspires and troubles Klein. While she notes that she loves all historic cemeteries, she has a soft spot for this one since she grew up in Plymouth and recalls visiting Burial Hill as a child. Through her doctoral program, Klein worked with Antoinette Jackson, an anthropologist at the University of South Florida and founder of The Black Cemetery Network, which protects historically Black cemeteries through research and advocacy. Jackson’s work motivated Klein to preserve the cemetery she loved as a young student by digitizing gravestones.

“The view from on top of Burial Hill is amazing, and I can’t imagine what it would have been like 300 years ago, 3,000 years ago,” Klein says. “So [I’m] trying to capture some of that and share it with other people.”

ACCESSING HISTORY WITH DIGITAL ARCHAEOLOGY

Since the inception of the Burial Hill 3D Digitization Project in 2021, Klein has documented more than 75 gravestones with the help of volunteers from Friends of Burial Hill and her sister, Menden. She has also planned and conducted workshops to teach volunteers how to do photogrammetry.

“That’s part of the accessibility,” Klein says. “More people can contribute to this. You don’t need to have a US$2,000 camera. You can just use your phone that you have on you anyway.”

Klein sees digital archaeology as a vital tool in the present and future of public archaeology. Bringing important sites and heritage online, such as her work digitizing gravestones, makes them accessible to anyone with access to the internet, whether they are down the street from Burial Hill or halfway across the world.

“Especially [since] COVID, everybody really relies on digital tools to make their collections accessible,” she says. “This is the next step in archaeology. Everybody is going to know how to do photogrammetry.”

Klein also hopes her project will aid in preservation and conservation. Once gravestones are damaged or worn away, it is impossible to repair or replace them without a detailed record. With digitized 3D photographs, Klein says, “the town and the cemetery keepers could track things like organic growth on individual stones or damage. Or if a tree falls this winter and takes out 20 stones, if we have those models, then they can create a 100 percent accurate stone.”

Klein says a similar method was recently used at a historic cemetery in Philadelphia. Researchers took laser scans of gravestones in a U.S. Naval plot and created a database that can be consulted for future repairs.

But environmental damage isn’t the only challenge Klein faces. The more she works on this project, she says, the more she encounters ethical puzzles that have not been adequately addressed in similar archaeological projects.

DIGITAL ARCHAEOLOGY AND DECOLONIZATION

The field of archaeology is increasingly coming to terms with its colonialist roots. Scholars are asking what decolonization should look like—or if it’s even possible. Klein is keenly aware of this as she works to preserve Burial Hill’s history.

Most of the people buried in the cemetery are early English colonists and White descendants of the Puritans who sailed on the Mayflower and were later called Pilgrims. These are some of the most quintessential characters in American lore. Indeed, they partly inspired a beloved holiday: Thanksgiving.

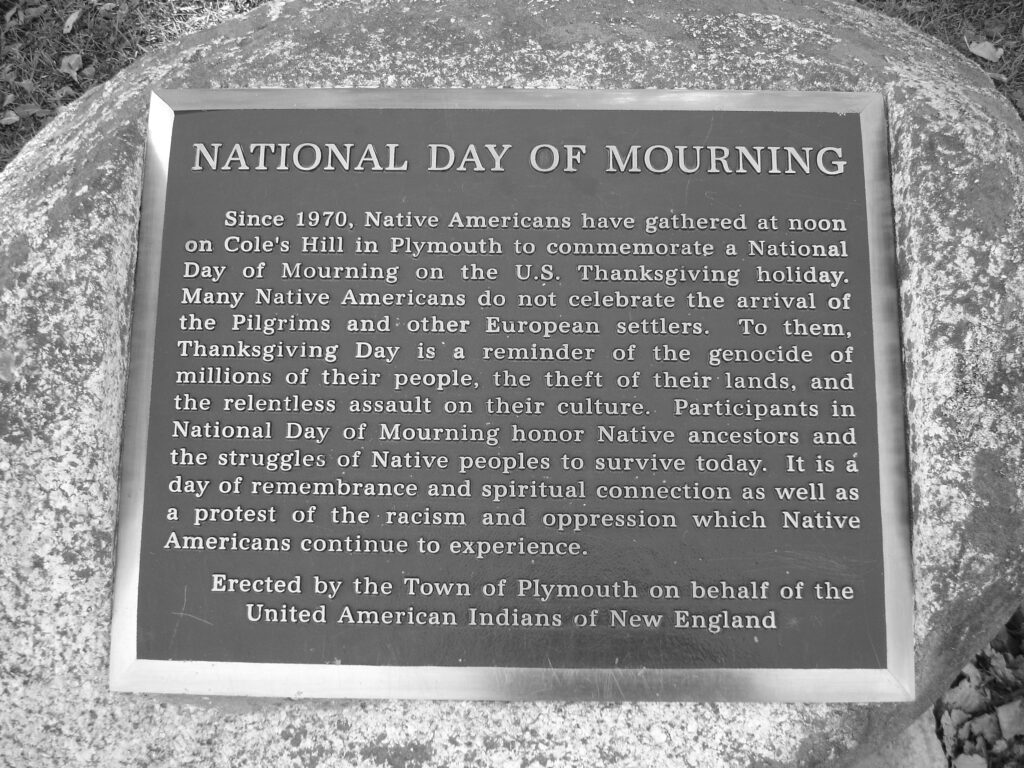

According to the Thanksgiving story as it was reimagined in the 1860s as a model of unity amid the U.S. Civil War, the thriving Pilgrims invited a few of their Native American friends to celebrate a bountiful harvest with a feast. Although there was in fact a shared feast in 1621, this version heavily sanitizes the violence that colonists would come to commit against Indigenous people in the region. It erases the fact that Native American communities already held celebrations of thanksgiving and taught the Pilgrims how to survive. Today a National Day of Mourning is held in Plymouth on Thanksgiving Day to remember the genocide and protest the continued oppression of Indigenous peoples.

“I grew up in Plymouth and was not taught about Thanksgiving. I moved away to Tennessee before I learned about what Thanksgiving was really like,” Klein says. Helping people understand this history and to uplift the perspectives of Indigenous and other marginalized people is a major guiding force in Klein’s pursuit of public archaeology.

“A huge part of this project is: How do I decolonize this project that is almost 100 percent colonizers?” she says. While Klein understandably does not have a neat solution to this big question, it permeates her research methods.

On one of the first days she spent on the hill with her camera, Klein photographed two lesser-documented burials she felt required more care. One was the gravestone of Charles B. Allen, a Civil War veteran who fought as part of the Fifth Massachusetts Colored Volunteer Cavalry, Massachusetts’s only all-Black cavalry regiment. The other was the grave of Nancy Williams, a Black woman who worked as a servant and who passed away at the age of 25.

Though little is recorded about these people, Klein wants to preserve as much of their stories as possible. “I can’t imagine what their life was like, and so at least being able to record their stones, their memory lives on, and we can continue to care for their stones,” she says.

“There’s some quote about how you’re not forgotten until someone doesn’t say your name anymore,” Klein says. Through her dedication to digitizing gravestones—the thousands of names and stories on Burial Hill—Klein is making sure these lives are not forgotten.