Unearthing Culinary Pasts—With Help From Llama Poop

A DAY IN THE LIFE OF A FOOD ARCHAEOLOGIST

On a sweltering day in the Peruvian desert, my field assistants and I were fighting heat-induced hallucinations as we dug through the remains of a 1,500-year-old house. The glaring sun turned everything indistinguishable shades of tan. As we excavated the corner of a small square-shaped room, something caught my eye.

“Llama poop!” I exclaimed.

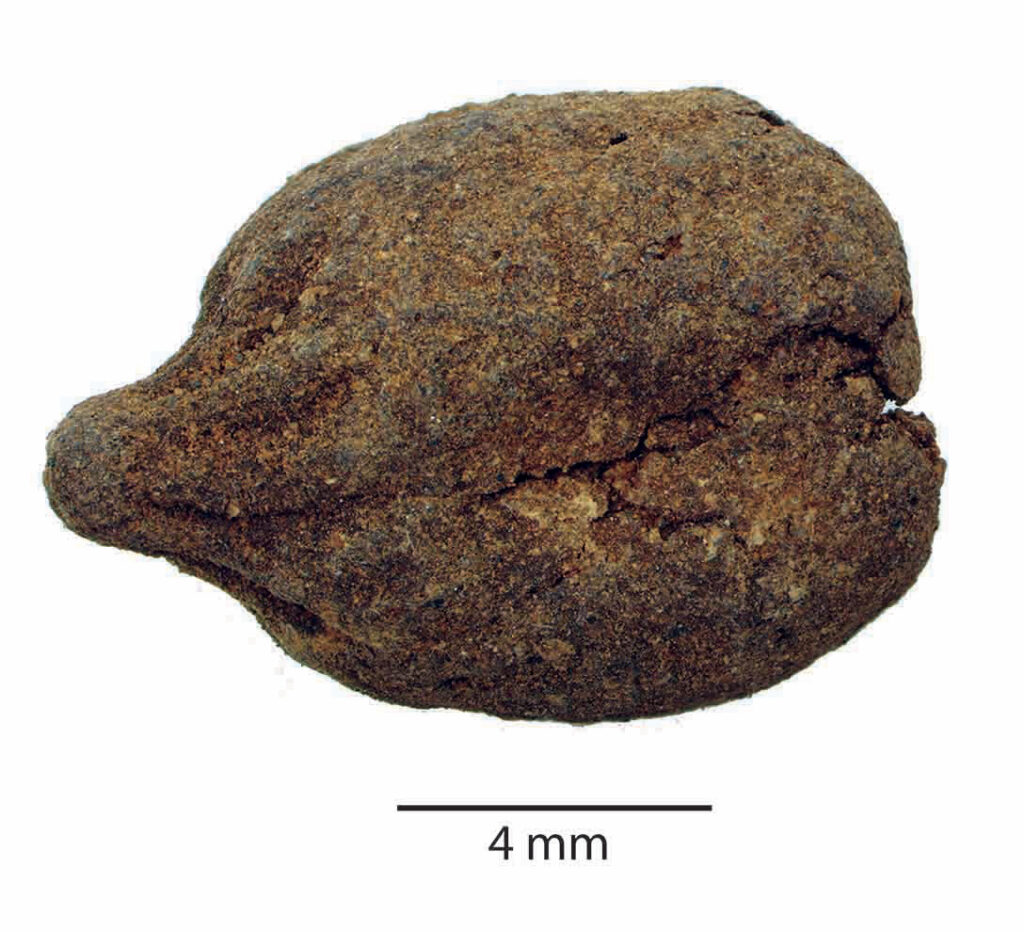

Just a few of the round pellets emerged at first. But as we dug deeper, we uncovered hundreds and eventually thousands of the “beans,” as they’re commonly called. We also found seeds, tubers, and animal bones.

This was a treasure trove of information about ancient meals—the stuff of archaeologists’ dreams. I nearly cried.

As a food archaeologist working in Andean South America, I am fascinated by the banality of everyday habits like eating. Compared to the construction of great temples or practices involving ritual sacrifice, ancient eating practices might not capture people’s imaginations in quite the same way. But the remains from more mundane human practices can tell researchers so much about past lives.

Listen here to learn more about Chiou’s food research: “People of the Peppers.”

The llama poop, in this case, is associated with the Moche, a group of people who lived in present-day Peru from roughly A.D. 100 to A.D. 850. Based on this remarkable (in my humble opinion) finding, we now know that the Moche collected dung from their domesticated llamas and alpacas. They mixed the poop with water and food scraps to create a compost rich in nitrogen, potassium, and phosphorous.

Why is the discovery of a simple compost bin important for archaeologists? These llama beans, while seemingly insignificant, provide clues to how the Moche survived during times of drought, conflict, and political collapse.

Many societies across the ages, including our own, have faced or are facing similar tensions and catastrophes. Understanding how past societies such as the Moche navigated such social upheavals, whether successfully or unsuccessfully, can provide valuable lessons for today.

NEARING THE END TIMES: CONFLICT AND DISASTER

The Moche of ancient Peru are considered a “complex society” that predated the more famous Inca civilization by around 1,000 years. Moche peoples created impressive art and monumental architecture, including a wide network of irrigation canals to turn swaths of desert into fertile agricultural land.

Archaeological evidence suggests, however, that during their waning years in the 7th and 8th centuries, Moche communities faced internal political and social turmoil.

The data I’ve collected on meals eaten by the elite in Moche society suggest that the rich “got richer” while others experienced insecurity. Public displays of ostentatious wealth such as elaborate burials and ritual feasts held by the upper crust likely shone a glaring light on the gap between the haves and the have-nots.

To make matters worse, people were contending with other social stressors including possible foreign incursions coming from the Andean highlands and/or other local groups. While archaeologists have not found direct evidence for outright war in this period, the proliferation of defensible settlements suggests the Moche were worried about security. They might have feared raids on their communities for supplies, captives, or land.

Beyond class-based tensions and the possible threat of violence, the Moche were facing a series of severe droughts and floods in the sixth through seventh centuries. These environmental disasters would have likely threatened their lives in the desert—an area of the world where water is already scarce. Fights over limited water access and supply probably heightened competition and caused relations to deteriorate between communities.

All these compounding factors ultimately created rifts in the social fabric that led to the end of the Moche as a dominant political entity.

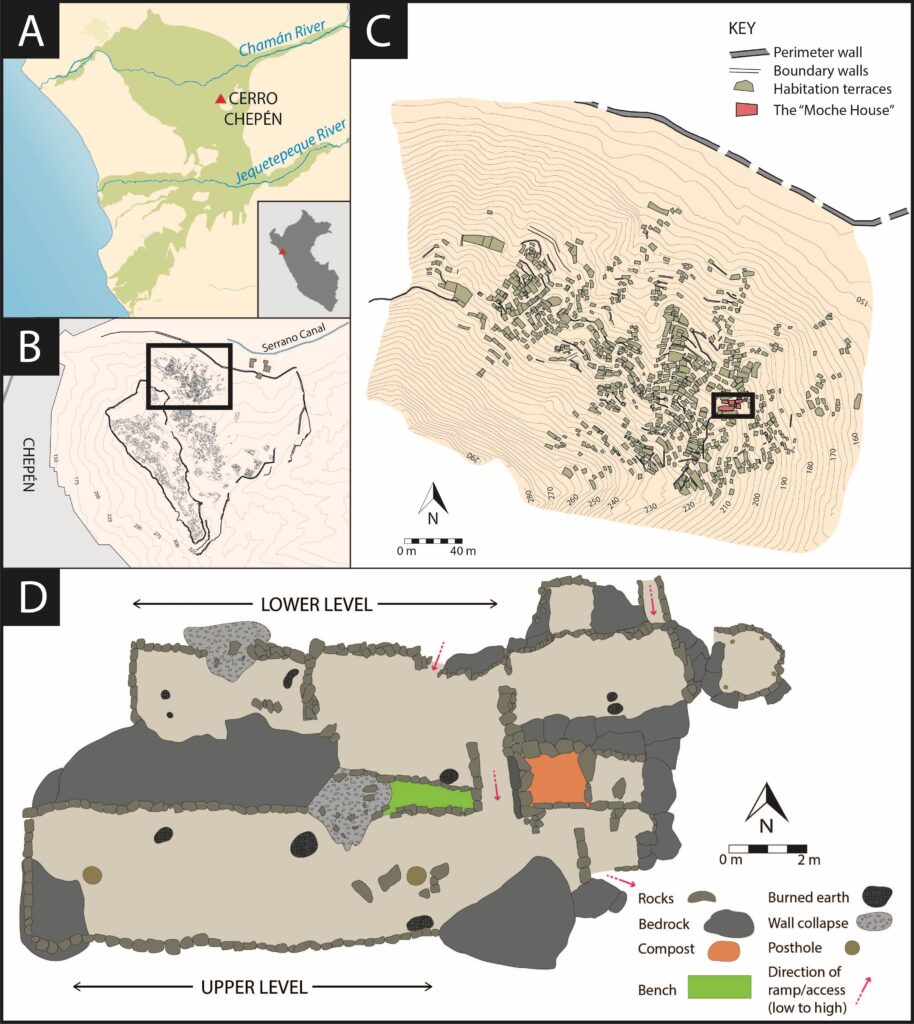

EXCAVATING CERRO CHEPÉN

In the Jequetepeque Valley where I did my research, signs of the Moche’s crumbling grasp on centralized power and control are built into the landscape. Toward the end of their political reign, the Moche began constructing fortified towns in the hinterlands on hills near productive lands with access to water. One such community, where my team discovered the llama beans, is the site of Cerro Chepén.

Like other settlements created around that time, Cerro Chepén was hastily constructed and occupied for a short amount of time to strategically secure a portion of the valley. In what archaeologists refer to as the Hilltop Community, the elite lived in grand buildings protected by a towering defensive wall with limited entry points—similar to today’s gated communities. Their diets likely included corn, various fruits, and a wide variety of animal protein, particularly marine foods.

Meanwhile, in what we call the Hillside Community, commoners dwelt in houses built on terraces and platforms. Those occupying the lower social rungs would have been far more exposed to threats and closer to water and farmland. Their diets were more limited in comparison to the Hilltop dwellers.

Like all people living through times of uncertainty, those living in the Hillside house my team excavated had adopted strategies to cope with an unstable food supply. For one thing, they seemed to stay closer to home than previous generations. Archaeologists looking at earlier periods have found that Moche commoners likely foraged far across the Andes’ diverse ecological zones. By comparison, the diet of the Hillside dwellers at Cerro Chepén indicates they had become more risk averse than in the past, choosing instead more localized and dependable food sources.

My analysis of the compost bin shows Hillside commoners relied on a core group of staple foods grown nearby, such as maize, algarrobo, cassava, and squash. They kept guinea pigs in their homes and tended llamas outside, using them as their primary sources of animal protein. They indulged in land snails found on cacti growing on the hill and foraged for wild, weedy plants such as amaranth in the surrounding agricultural areas.

In addition to sticking to simple and more readily accessible ingredients, residents also saved the remnants of their meals and mixed them with llama beans from nearby corrals to create their compost pile. To aid in the decomposition process, they added water and regularly turned the mixture to ensure proper aeration. This produced a rich fertilizer that could be used in their gardens and fields to increase agricultural yields.

At some point, the entire community of Cerro Chepén left their homes, but it’s not clear why. It’s possible that the area was attacked—but it could be that people simply moved away. They also could have been driven out or forced to move to higher elevations due to drought.

What we do know is that when the Hillside Moche house was abandoned, a load of compost was in the midst of breaking down. Without proper attention, the decomposition and recycling process was halted, preserving the contents.

Fast forward more than 1,000 years, and archaeologists like me are left to marvel at the ingenuity and resourcefulness of those who came before us.

WHY FOOD ARCHAEOLOGY MATTERS

So, what’s the most important takeaway from this research?

Understanding disparities in food access among the Moche is important in part because it demonstrates how class inequalities may have contributed to the political downfall of the society.

At the same time, investigating eating patterns helps us understand how people survived and endured despite such challenges. My research suggests staple plant and meat foods may have been a symbol of shared identity for the Moche lower classes. In times of hardship, these familiar foods may have brought people together and helped them persist.

Around the world today, people continue to embrace simple, nostalgic foods—sometimes called “struggle meals”—for a sense of belonging within a community. Consider beloved dishes made from less desirable meat scraps and offal, such as scrapple, salami, and braised oxtails, or soups and stews that stretch ingredients, such as menudo, cassoulet, and acquacotta. Starchy dishes with humble origins made from staple crops also bring comfort to many eaters: Think colcannon, polenta, congee, or red beans and rice.

By looking into past societies like the Moche’s, we can better understand how humans turn to food to navigate stressors such as inequality and environmental change. Today when we look at some our favorite humble dishes, we should consider the stories they tell about the resilience of past generations.

In other words, don’t neglect caches of old llama poop and garbage! We can learn a lot from them.