Making Love—and Nations

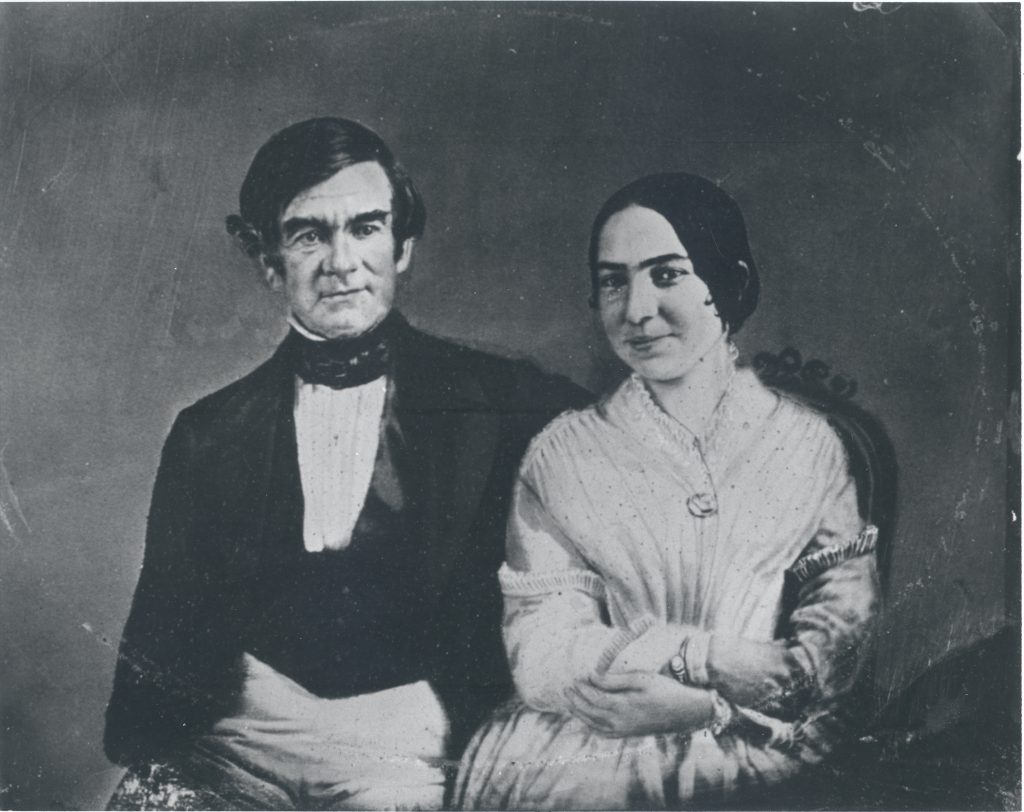

Staunchly opposed to marriages outside his nation, John Ross, the principal chief of the Cherokee from the late 1820s until his death in 1866, helped introduce restrictive laws against intermarriage between Cherokee women and white men. Ross, also known as Kooweskoowe, famously forbade his relatives from marrying outsiders. Yet, after his Cherokee wife died, he courted women in the elite circles of white American society. Mary Brian Stapler, a young white woman from Wilmington, Delaware, became the great love of his life, and their courtship and eventual marriage led to one of America’s epic romances. At the same time as Ross was negotiating his nation’s treaty with the U.S. government, he was working on his own “treaty,” as he called it, with Stapler. His courtship letters were sent from Washington, D.C., New York, and the Great Plains.

Love stories, especially those between Native peoples and newcomers, are usually left out of national histories. But the story of people connecting, pairing, having families, departing, dividing up, and doing it all over again is central to how the world’s peoples and cultures came to be. So why is love, so clearly at the core of human experience, or, more specifically, love across cultural boundaries, a missing plot line?

Historically, in both the United States and Australia, these unions became like state secrets that had to be kept under wraps since they posed problems for nations on both sides of the frontier. These integrated families blurred the dividing line between colonizer and colonized and countered colonialists’ dreams of seizing new lands and subjugating Indigenous people.

Where Europeans and Indigenous peoples first encountered each other, they fought over land and resources—and women. On many frontiers, or what I call “marital middle grounds,” settlers negotiated the novel marriage practices they encountered. By respecting local marriage protocols, white frontiersmen avoided violence and gained access to the local political, economic, and environmental knowledge networks needed to sustain themselves on unfamiliar land.

Yet, for colonial elites, such relationships threatened to disrupt what they hoped would be a forward expansion of the frontier. Indigenous peoples’ marriage systems allowed for the “uncivilized” practices they rejected, such as inheriting land and property through the female line and polygamy. Settlers and their new families integrated into worlds where Indigenous rights still mattered. However, the enforcement of its own legal and cultural system was fundamental to colonial power.

As American colonies matured, their new social order increasingly suppressed marriages between European newcomers and Native Americans. The marriage of Pocahontas, Chief Powhatan’s daughter, and the Englishman John Rolfe in 1614 has long been romanticized as a kind of royal alliance. Yet, the colony of Virginia— from which Pocahontas was kidnapped—was one of the first to introduce laws against intermarriage between Euro-Americans and Native Americans, doing so in 1691. Particularly during the 1800s, many states barred marriages between ethnic and “racial” groups. The U.S. Supreme Court did not declare laws prohibiting interracial marriage unconstitutional until 1967.

Such laws were in place in colonial settings around the world. In Queensland, Australia, for example, white officials solidified the ban on marriage between white men and Aboriginal women in 1901—the same year the federated nation of Australia came into being. This was no coincidence. But love perseveres. For instance, Australian frontiersmen sought permission to marry their Aboriginal sweethearts, but these requests were often denied. In the new state of Queensland, children from these relationships were understood as “illegitimate” on the basis of their mixed descent, and because they were the product of “illicit” unions and unrecognized marriages. As a result, government officials took these children away from their parents. Lacking the love and protection of family, many ended up suffering in institutions.

I grew up in Queensland during the 1960s when racial discrimination was still so rife that many Queenslanders kept their Aboriginal ancestries secret. Keeping family secrets became commonplace. Not only had Aboriginal people supposedly just “gone” from the landscape, with no heroic battles, but according to what we were taught in school, it was as if they had never shared the same spaces—let alone fallen in love, gotten married, and loved their children.

As a child, I wondered why this was so. When I became a historian, I started to investigate the history of colonialism, which led me to the topic of intermarriage across colonizing boundaries. The history of love, above and beyond other themes, promised clues that would help me understand what lurks beneath the surface of history. These forgotten secrets are the private stuff that makes our nations tick.

Exploring the stories of lovers who crossed boundaries on colonial frontiers soon became one of my research obsessions. Guarded as both familial and national secrets, these people’s loves and lives were located at the very heart of national concerns, at precise junctures of nation formation. Community outrage and legal action against these unions left indelible living legacies that have ongoing political implications. Such relationships became a key element in creating but also destroying connections between New World nations, thus shaping the texture of these budding nation-states.

Some years ago, in search of clues about why Ross, the Cherokee chief and anti-intermarriage advocate, had decided to marry a white woman, I visited the Gilcrease Museum archives in Oklahoma. In the archival reading room, I untied a white ribbon and opened the John Ross Paper’s manila folder 5326.290. Inside, protected by old paper inscribed with Indian ink, were the corpses of flowers.

A spray of fine twigs and a bud had been tied up with string. Powder dry, faint imaginings of color tinged the otherwise sepia remains. Maybe the stems were once a sprig of cedar, or lavender. The bud was crushed almost flat—a ghost of a red rose.

Then I read the paper’s notation: “Presented to Mrs Mary B. Ross By Mrs Madison the widow of Ex President [James] Madison.”

The file is dated Sept. 2, 1844, the day of Stapler’s marriage to John Ross.

Was marriage across cultural boundaries good or bad for these new nations? On the one hand, unions across colonizing boundaries were widely viewed as being against the tide of progress toward “modern white nations.” And yet, some prominent figures, such as Dolley Madison, and her close friend the former President Thomas Jefferson, envisioned a different future. They believed intermarriage between Indians and whites could be advantageous for the young nation. (However, they were thinking about white men marrying Native American women, not white women with Native American men.)

On the other hand, boundary-crossing couples were the ones who held the potential to bind new worlds together. After their marriage, John Ross and Mary Brian Stapler Ross lived in Indian Territory in Oklahoma (although they had to seek refuge in the North during the Civil War). Mary Ross was welcomed by her husband’s family, and members of her family even moved to live with them permanently. The Rosses brought up their children as proud Cherokees, some of whom became prominent Cherokee leaders. Countless other stories exemplify this phenomenon, which I discuss in more detail in my book Illicit Love: Interracial Sex and Marriage in the United States and Australia.

In his later days, Ross shared a personal vision of the advantages of love between the citizens of the Cherokee Nation and the United States. He was an astute political operator. Such marriages expanded Cherokee networks into the heartland of New England trade, diplomacy, and philanthropy. At the same time, the Cherokees’ own restrictive intermarriage laws reflected their political, often race-based, efforts to maintain control of their nation, treaty entitlements, and sovereignty.

Illicit love across the frontier shaped the very constitution of colonial nations such as the United States and Australia. It is this courageous love that created the families and the new generations that brought long separated peoples together on the same land.