What Egyptian Pharaohs Can Tell Us About Modern Tyrants

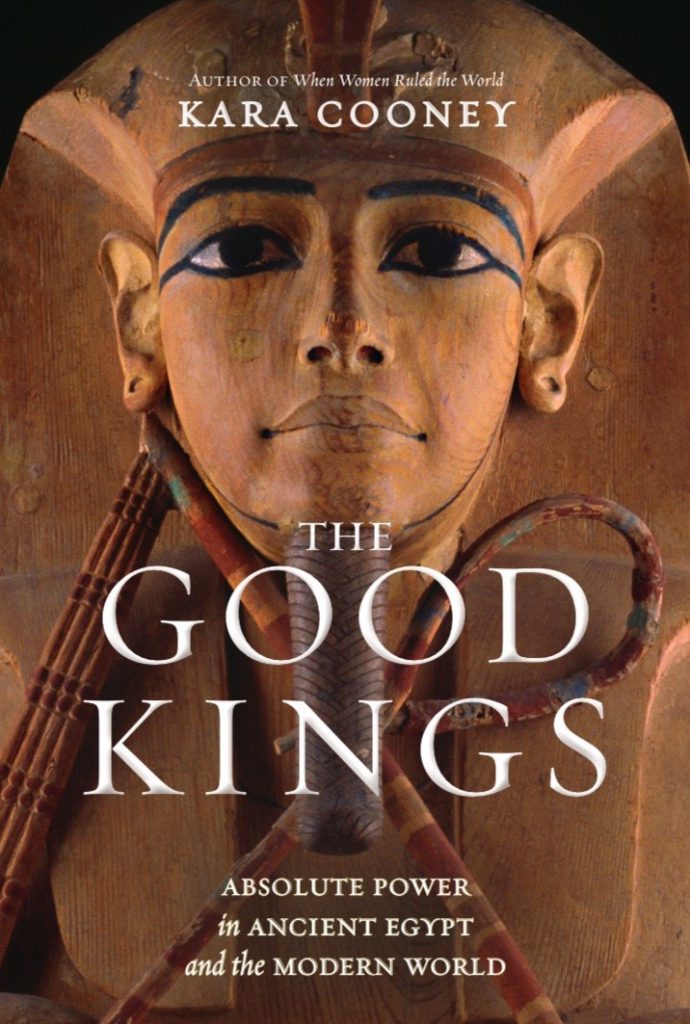

Excerpted from The Good Kings. © 2021 by Kara Cooney. Published by National Geographic Books. Courtesy of National Geographic Books.

I am a recovering Egyptologist.

Like many of us in the field, I was initially attracted to the subject because of some unexplainable, irrational love for an ancient culture that lay millennia in the past. Maybe I was drawn in by the dazzling gold, the massive statuary, the pyramids whose codes have yet to be cracked, the unabashed displays of power. Or maybe I fell for the idea of divine kingship that could reify miracles in stone and craft philosophical tales of complex religiosity.

But that unassailable strength of ancient rule, once so attractive to me, has now soured. The realization was like suddenly understanding that you’re in an abusive relationship.

I can’t help but view my once beloved Egyptian kings—and their stunningly beautiful artistic and cerebral productions—in light of the testosterone-soaked power politics of the patriarchal system in which I live in the U.S. I am quickly becoming anti-patriarchal and anti-pharaoh, in whatever form the absolutism takes, ancient or modern. I now dwell in a strange in-between world in which the script has been flipped, where those gorgeous, chiseled kings have been revealed as bullies and narcissists.

I’m being naive, you might say. And, of course, you could be right. But how many of us have had deep obsessions with the ancient world—I just love Egyptian temples! I adore Greek mythology!—that are really symptoms of an ongoing addiction to male power that we just can’t kick?

This book presents an analysis of how we make ourselves easy marks for the next charismatic authoritarian to come along. It’s high time we see how fetishism of ancient cultures is used to prop up modern power grabs. And many of us need to admit—somewhere down deep—that we think the powerful patriarch, coolly in control, is superhot. Only then can we actually figure out how to smash him.

Anti-patriarchal thinking doesn’t mean being anti-male; I have a son and a husband, and I love and support them both. Being anti-patriarchal means refusing to support a “rule of the fathers,” in which a few masculine elements of society pull most of the resources to themselves: a scenario in which fear, violence, threat, shame, and moralizing are used to keep everyone in line.

If we want a more just future in which we all have equal opportunities—the same chance to pursue prosperity and happiness—then the patriarchy has to go.

Read more about the reaction to The Good Kings in “Egyptology Has a Problem: Patriarchy“

I work in a field of apologists who believe in an Egypt of truth, beauty, and power—and in many ways, I am still an adherent to my chosen faith. We can’t simply cancel ancient Egyptian culture. There is much beauty in ancient Egypt, and I am not here to deride or belittle it.

Instead, I think the ancient Egyptians can help us recognize the king in our own system, show us how he behaves, and thereby teach us how we might neutralize him ourselves. We are all subject to our short lifetimes, which makes seeing the long term difficult, but we can look back in history and watch the ancient Egyptian dynasties rise and fall.

For millennia, Egypt engaged in a push-and-pull relationship with the monarch. Sometimes he was strong; sometimes he was weak. Sometimes the country got out from under the heavy boot of absolute power, only to slip back under it. But throughout those ups and downs, Egypt maintained a flourishing continuity of religious ritual, language and literature, artistic production, and cultural beauty. Egypt didn’t need its kings; the kings needed Egypt. It’s useful to remember that.

The kings of ancient Egypt can help us decode the tactics of the patriarchal system under which most people live. There was Khufu, the tax-and-spend creator of pyramid propaganda; Senwosret and his absolutist crackdowns; Akhenaten, the evangelical king; Ramses II, the needy populist; and Taharqa, the colonized imperialist. Those rulers were all products of their time. Today we create our own kings (perhaps at a faster clip because technology speeds up our political development).

Perhaps you think ancient Egypt shouldn’t be compared to any other regime—most especially, a modern state. But keeping ancient Egypt separate and vacuum-sealed allows us to fetishize it, to see the believers in these god-kings as primitive, silly people, nothing like us. Isolating any ancient culture to such a degree demands a belief that we would never fall for such manipulations by primeval demiurges.

With one state after another succumbing to authoritarianism while calling it democracy, though, we need to leave the safe confines of our modern exceptionalism behind. As we dissect our own cultural understandings of patriarchal power, ancient Egypt provides a useful lens.

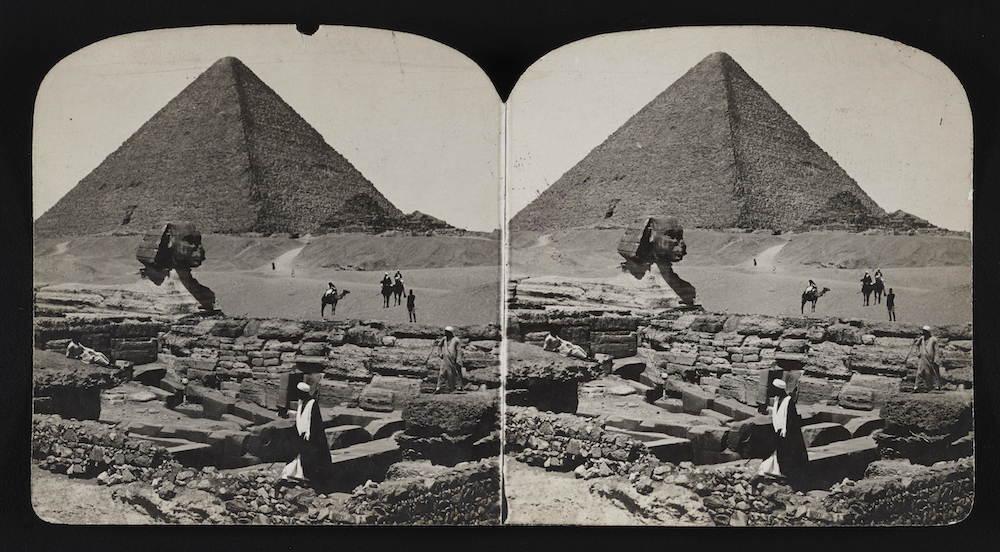

Hotly contested debates in 2020 about Confederate monuments in the United States, as well as statues of those who benefited from the slave trade or colonialism throughout the world, inspire the defensiveness of cultural apologism. When people assert that a particular statue of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee must come down, defenders of the status quo retort that we should tear down the pyramids, too, resulting in a common response from many an Egyptologist who rallies around the kings’ tombs to say: “These monuments were not built by slaves but by Egypt’s people!”

It’s worth noting, though, that both perspectives defend an authoritarian regime. Jim Crow statues and Egyptian pyramids represent the same masculine repressive powers; the only difference is the millennia separating one from the other—long years hiding the deep wounds carved into Egyptian flesh in the same ways that scarred U.S. society. And the distinction between slavery and draft labor is meaningless if participants were forced to take part.

Make no mistake: The Egyptian pyramids were built because the kings needed them. Just like statues of heroic Confederate Army generals on horseback, the Giza pyramids are signs of a crackdown after a loss of power. However, neither kind of monument is evocative of absolute strength; Confederate monuments and pyramids alike embody a kind of political rally to an insecure toxic masculinity that must impose its will and constantly remind people of its god-given superiority, lest it be lost.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not advocating for the destruction of the pyramids any more than I am pushing to melt down statues that reify Black oppression in the U.S. I am pushing for a reframing of every such monument, a paradigm shift that allows us to recognize how they cast a shadow over the power that abides there.