Preserving Black Women’s Stories as a Labor of Love

Stories about the lives of Black women often do not get preserved in the historical record. Anthropologist Irma McClaurin knows this all too well.

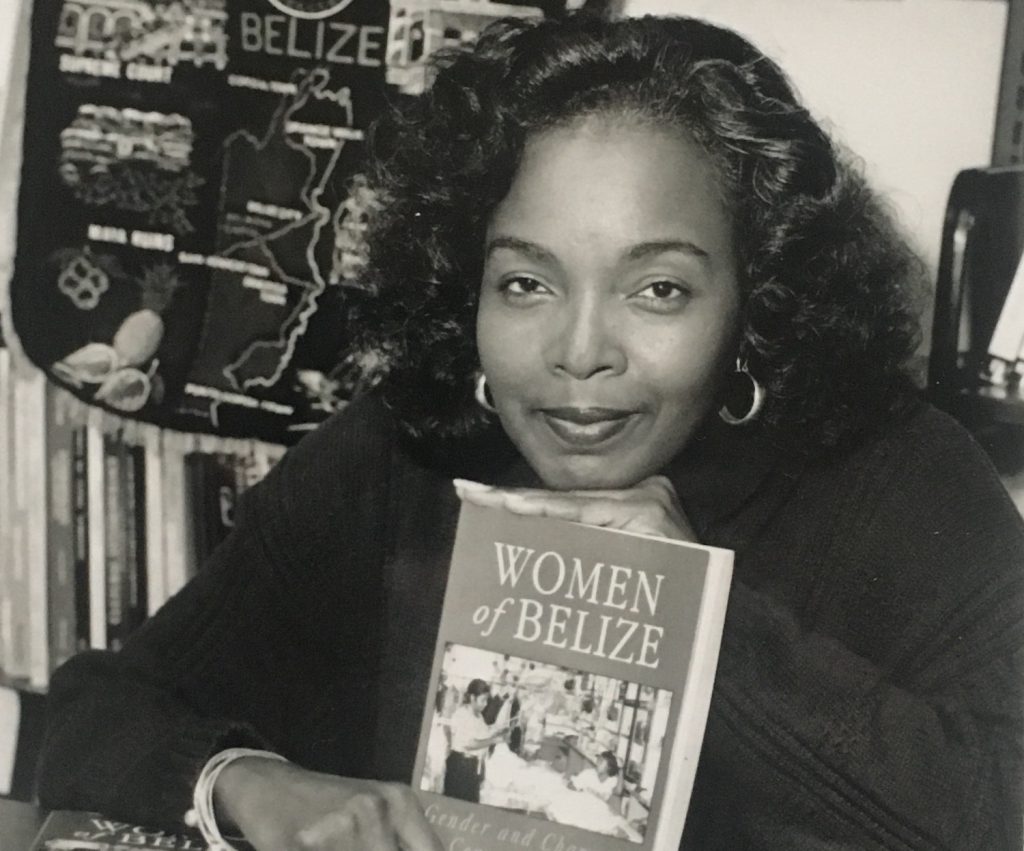

Around two decades ago, McClaurin started digging into the archives for a research project on Zora Neale Hurston, an acclaimed writer, poet, and playwright active during the Harlem Renaissance. Hurston’s career as a trailblazing anthropologist is less documented than her literary persona—likely because her fieldwork centered on her own community in Eatonville, Florida, and other Afro-descendant peoples and traditions throughout the Americas at a time when these issues were largely disapproved of in academic spaces. In researching and writing about Hurston over the years, McClaurin found huge gaps in the archival record—but the documents that were preserved gave her invaluable insights into Hurston’s life and career that other scholars had missed.

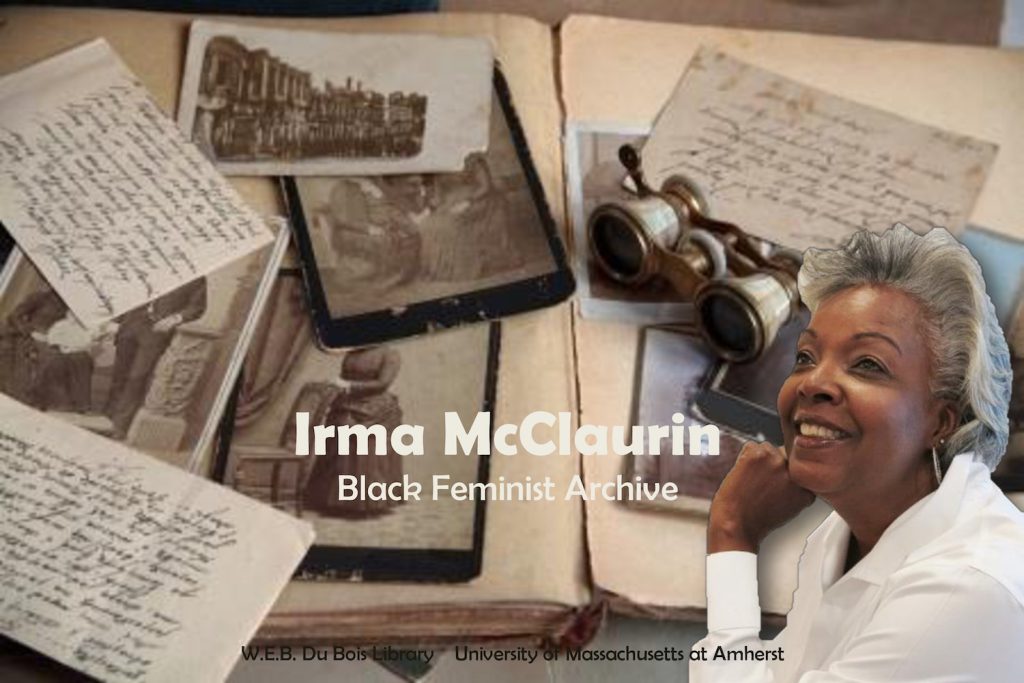

That experience—along with others throughout her long career as an activist scholar, Black feminist speaker, poet, award-winning columnist, and consultant—compelled McClaurin to eventually start her own archive in 2016. The Irma McClaurin Black Feminist Archive (BFA) at the University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries is a growing repository of materials that reflect Black women’s intellectual contributions from across the African diaspora.

SAPIENS fellow and anthropologist Eshe Lewis spoke to McClaurin by Zoom in August. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why were you drawn to archival work?

I began very early on to save things. My mother saved the poetry books that I started writing when I was 8 years old. I understood that the drafts of my poems were as important as the finished product. It was important for me to see where I started and not just where I ended up. I would keep poems, correspondence with people, cards—so I was already beginning in some ways to curate my life.

You’ve spent a lot of time in the archives researching Zora Neale Hurston. What did you learn through that process?

In 2000, I received a fellowship to conduct research in the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University, where one of the largest collections of Zora’s papers is held. (The other major collection is at the University of Florida—but it was almost lost. There are horror stories of Zora’s papers almost being burned and someone snatching them out of the fire.) At Yale, I was in search of Zora’s anthropology journals and fieldnotes. And they don’t exist. I contend that probably Zora put things in storage, and then she would run out of funding and wouldn’t be able to retrieve them.

I did discover and write about a series of letters between her and poet Langston Hughes (with whom she had a notoriously complicated friendship) where she describes her fieldwork. When you read Zora’s letters, you can see the germination of her ideas about Black life and culture. Those letters are only in the Beinecke Library because a man named Carl van Vechten, who knew the head librarian at Yale, asked Zora and Langston to contribute their papers. Zora sent the original manuscript of her novel Their Eyes Were Watching God to the Yale library to preserve. She also made greeting cards and wrote poems, and included those things as a way of telling her story.

When people do scholarly analysis of figures like Zora and Langston, they often miss these things—but these documents, these personal items—are available today because someone asked them, in a sense, to archive themselves.

I think it always stood out in the back of my mind, such that I would ask myself, “What’s going to happen to my stuff?”

What have you learned about power and legacy in this process of building an archive?

I don’t come from great wealth. I don’t come from a very long tradition of people going to college. I am very aware that I walk with privilege now, but that is not part of my history. So, I’m very attuned to how we preserve the things of those who don’t have the access or the privilege of working at a university.

All of that has driven me to want to build a legacy, to leave something tangible behind. Naming the archive after myself is very deliberate—because so often, if we’re not famous, we get lost. So, I wanted it to be the “Irma McClaurin” Black Feminist Archive.

And let’s face it: We live in a culture that values writing and papers. We can preserve a level of oral tradition, but it is the words, the papers, and the photographs that matter most right now.

Most importantly, in being my own curator and archiving my own work, I get to shape the narrative of my life. That is true empowerment.

What distinguishes your archive from other projects like it?

What makes the BFA different is that it’s a collaboration between myself and the Special Collections and University Archives at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and with the W.E.B. Du Bois Center. They provide the technical expertise, but the vision is mine. When I invite people to be part of the archive, I stress that they have agency. The contributors should be the ones actively telling the stories and formulating the descriptions in the archives, as opposed to having some outside person decide and impose what they think is going on.

In this moment—after the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and too many others to name—institutions are rushing to collect Black “stuff.” But my work is not just responding to the current moment. It’s about creating a permanent safe space—a “home” for Black women.

What message does this project convey to Black women and their communities—and to society and academia?

I want to let Black women know that our lives, our ideas, our work as community activists deserve to be preserved. When I first began, I did a presentation at a conference for Black women law professors. I ended my talk by asking, “How many of you have thought about archiving your work?” In a room of 124 Black women, one raised her hand—and that was only because the librarian at her university had come to her and suggested it. Not one of the others thought what they were doing was worth archiving.

Partly this is due to the belief that you have to be a celebrity to have your work archived, and in many respects, that’s what the field of archiving has said to us. Eight-three percent of all archivists are white. [1] [1] In this article, white is styled lowercase throughout, contrary to SAPIENS’ house style, at the request of the author. Only about 4 percent are African American.

You recently received two grants from the Wenner-Gren Foundation—which is also SAPIENS’ publisher—to continue developing your archive, specifically to preserve the work of Black feminists who have played a significant role in the field of anthropology. What does that mean for the archive?

I have reached out to everyone who contributed to my edited book Black Feminist Anthropology and asked them to contribute. Distinguished African specialist Carolyn Martin Shaw’s papers are already in the collection. Former American Anthropological Association President Yolanda Moses has said she’ll put her papers in there. I have materials that relate to former Spelman College and Bennett College President Johnnetta Cole. The latest Global Initiatives Grant I received will allow me to collaborate with the Association of Black Anthropologists to do workshops on Black self-preservation through archives for Black graduate students and junior faculty.

The grant will also allow me to focus on identifying Black female anthropologists who work outside academia. Not everyone presents as trained anthropologists and not everyone is affiliated with an institution. Some people are out in their communities doing cultural preservation. In my article “Visible and Heard,” I talk about Miss Archie Jones, a Black woman who conducted anthropological research about her community. She’s now 97 years old. You’re not going to find her papers in Google Scholar and JSTOR because at the time she was doing her research, they weren’t publishing a whole lot of Black folks, particularly Black women.

In deciding who to invite into the BFA, I’m being very flexible. I feel strongly that if someone has completed an undergraduate degree in anthropology, or has informal experience with ethnographic research, then they should be included. The history of anthropology has often included white men who were archaeologists, though they were never formally trained. I want my archive to be inclusive—to not use a lack of education as a criterion for exclusion.

What do you want to leave behind? What would you like to see in an archive honoring you and your work?

I would say the breadth of the kind of writing I do. I began as a poet, then became an academic. My poetry has been published in over 16 magazines, including Essence, and in anthologies. Then there are my academic books.

More recently, I have published 100-plus articles in Insight News. After Trayvon Martin’s death in 2014, I wrote a column titled “A Black Mother Weeps for America—Stop Killing Our Black Sons!” The National Newspaper Publishers Association, the professional organization for the Black Press of America, selected it the “Best in the Nation for Column Writing” in 2015.

And then there’s my leadership career: I was the president of Shaw University, a program officer at the Ford Foundation, the chief diversity officer at Teach for America, and more. Now I’m a consultant. The American Anthropological Association honored me with the 2021 Engaged Anthropology Award for my work with organizations and museums.

I’ve done some amazing things. So, I want people to see my versatility—how I perform my activism as a leader and reach different audiences in multiple ways as a writer.

How can the public interact with the Irma McClaurin Black Feminist Archive?

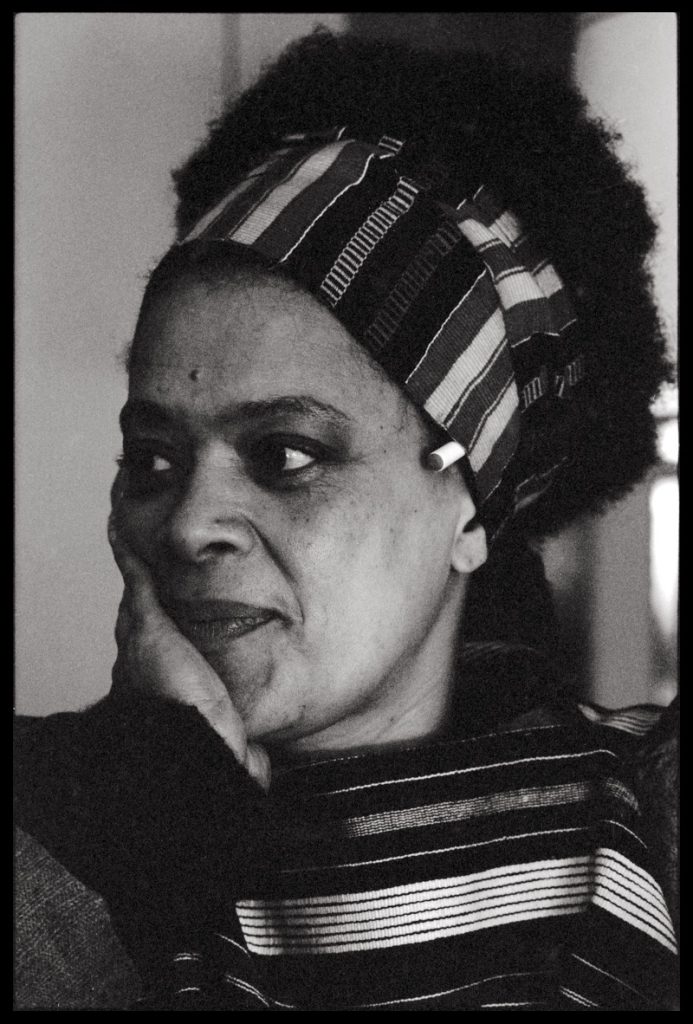

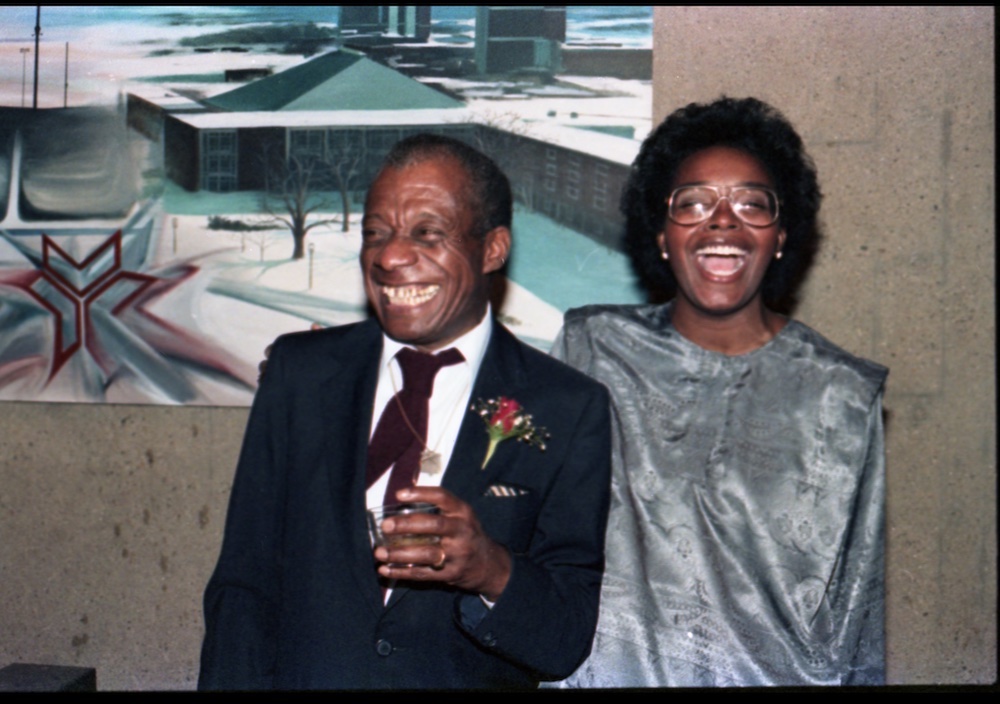

The BFA is developing. Some of the collection is already online. The library digitized 379 of my black-and-white photographs taken between 1974 and 1990—pictures taken in intimate, social settings. There are photos of writer James Baldwin’s birthday party, for example. In a lot of photos in the public record, he looks tense—like he’s trying to hold off attacks or address questions around white innocence, where people act like racism doesn’t exist. In my photos, Baldwin is smiling and at ease. I also took pictures of writer and activist Toni Cade Bambara.

We are in the process of building a platform on the UMass Amherst site to access the archive, but in the meantime, people can learn about it on my website.

Why does a project like this matter?

Historians and documentarians like Ken Burns do not just go and get stuff off the streets; they go to archives. If we’re not in those archives, then we will continue to get overlooked.

I hope at some point the BFA will grow into the largest of its kind in the world—an archive specifically devoted to identifying, curating, and preserving the contributions and stories of Black women who are activists, artists, academics, or just ordinary folk. People are here today and gone tomorrow. Their lives and work need to be preserved.

This archive is both my passion and my legacy. I have been given an opportunity to see it through, and that’s what I plan to do: build a huge archival home specifically devoted to people who look like me—to Black women.