Today most people around the world are using digital gadgets. These enable us to communicate instantaneously, pursue our daily work, and entertain ourselves through streaming videos and songs.

But what happens when our past digital activities become evidence in criminal investigations? How are the data that mediate our lives turned into legal arguments?

An anthropologist searches for answers.

Onur Arslan is a Ph.D. candidate in anthropology at the University of California, Davis, who works at the intersections of science and technology studies, visual anthropology, law, and social studies. He graduated from Istanbul University with a B.A. in political science and international relations, and from Bilgi University with an M.A. in philosophy and social thought. For his Ph.D. research, he is investigating how digital technologies reshape the production of legal knowledge in terrorism trials. Through focusing on Turkish counterterrorism, he examines cultural, political, and technoscientific implications of evidence-making practices. His field research is supported by the National Science Foundation, Social Science Research Council, and American Research Institute in Turkey.

Check out these related resources:

SAPIENS: A Podcast for Everything Human is produced by House of Pod. The executive producers were Cat Jaffee and Chip Colwell. This season’s host was Eshe Lewis, who is the director of the SAPIENS Public Scholars Training Fellowship program. Dennis Funk was the audio editor and sound designer. Christine Weeber was the copy editor.

SAPIENS is an editorially independent magazine of the Wenner-Gren Foundation and the University of Chicago Press. SAPIENS: A Podcast for Everything Human is part of the American Anthropological Association Podcast Library.

This episode is part of the SAPIENS Public Scholars Training Fellowship program, which provides in-depth training for anthropologists in the craft of science communication and public scholarship, funded with the support of a three-year grant from the John Templeton Foundation.

The Problems of Digital Evidence in Terrorism Trials

[introductory music]

Voice 1: What makes us human?

Voice 2: A very beautiful day.

Voice 3: Little termite farm.

Voice 4: Things that create wonder.

Voice 5: Social media.

Voice 6: Forced migration.

Voice 1: What makes us human?

Voice 7: Stone tools.

Voice 8: A hydropower dam.

Voice 9: Pintura indígena.

Voice 10: Earthquakes and volcanoes.

Voice 11: Coming in from Mars.

Voice 12: The first cyborg.

Voice 1: Let’s find out. SAPIENS: A Podcast for Everything Human.

Eshe Lewis: How can daily digital activities become evidence of a terrorism crime? And how much can we trust digital evidence? This episode comes to you from Onur Arslan. Onur is an anthropologist who studies digital evidence and terrorism trials and how it reshapes political and cultural relations in Turkey.

Onur Arslan: I’m an anthropologist and a Ph.D. candidate at UC, Davis. My work deals with law, technology, and counterterrorism. Specifically, I study evidence-making practices after the 2016 coup attempt in Turkey.

Eshe: I’ve never been to Turkey. I hear it is beautiful and fascinating, but I’ve never been. Can you tell me about the coup? How does it relate to your work?

Onur: Turkey is indeed a beautiful country. But we had hard political times recently. So this coup attempt happened on July 15, 2016, and the Turkish government said that the coup was organized by the Fethullah Gülen movement. It’s a religious network led by the U.S.-based cleric Fethullah Gülen.

In the seven years following the coup attempt, more than 2 million people have been investigated for terrorism charges, and most of the evidence used against them was digital data extracted from surveillance databases or personal network devices, personal gadgets. These are message contents, images, phone calls, or metadata that show the locations and times of digital activities.

So my research is about how these digital traces are extracted from these devices and turned into evidence for terrorism to be presented in the courts. And I’m also looking at what form of politics and what form of social relations these evidence practices create.

Eshe: This all sounds kind of scary and menacing and worrisome. Can you tell me how you came to this work?

Onur: Since I was a teenager, I have always been interested in political matters. But this is also based on my personal experience. You haven’t visited Turkey, but you probably know of the natural strait that divides the city and the two continents, Europe and Asia. So my neighborhood, Çengelköy, is one of the small coastal towns located at the very edge of the Asian side. This coastal town is famous for its seaside, its historical buildings, and also its historical church. It was an old Greek town.

After the 2016 coup attempt, and a day before, a group in the military just tried to overthrow the government, and more than 300 people had died or [were] killed in the clashes between soldiers and civilians. One of the fiercest fights took place in the streets where I spent my childhood and my youth, and I saw the streets covered with dried bloodstains and buildings full of bullet holes and a lot of Turkish flags.

But still, on that day, I and my neighbors, my family, were optimistic because a military coup was averted, thanks to the civilian resistance. But that hopeful atmosphere changed quickly because I witnessed a large state crackdown and change in the country’s political order. And I decided to work on the technological and political conditions that shape this shift to an autocratic governance. So I’m looking at the material conditions that make this autocratic governance possible.

Eshe: Can I go back to something that you were saying earlier when you were describing your work? You were talking about how your research focuses on digital traces that are turned into evidence of terrorism. What is a digital trace?

Onur: Let me explain this through an example. Let’s think about a person who listens to this conversation, right? And let’s say that person’s name is Ivan. So Ivan thinks that this is a very beautiful day to listen to a podcast. First, he finds his phone, unlocks it, and hopefully he has a good Internet connection. Then he opens the application, browses SAPIENS episodes, and chooses this one. And in this simple activity, he has left digital traces in at least three places: his phone, the servers that hosts the SAPIENS podcast, and the computers of the Internet service providers.

So the tech industry uses these traces for a variety of reasons; for example, for advertisements, for manipulating our choices—for the things that we buy—or to manipulate our political choices. But if one day, Ivan’s digital activity becomes a subject of criminal investigation, a digital forensic examiner or a computer engineer can collect that activity—even years later—extract data from it, and reconstruct Ivan’s digital activity. At this point, you [would probably] ask why we would need experts to do that. We can just take Ivan’s phone, unlock it, and just check the data.

But if you had done that, you would not be able to present that data in the courts because you need to see Ivan’s phone as a kind of crime scene to introduce that data to the court. When a crime occurs in the street, for example, the police will mark off a perimeter zone, restrict access, and shield objects from further contact. In other words, they suspend the scene in time and space to turn physical traces into evidence. Through these practices, you prevent decay or contamination or alteration of objects. So we need to do the same with data. We need to prevent the alteration of data after it is extracted. So ideally, of course, this should be done by experts. And you need devices. You need software. You also need people who know how to do this. And these are usually digital forensics specialists. So that’s why they are the ones who trace or who follow and track these digital traces.

Eshe: Who are these digital forensic specialists? What kind of work do they do? If we’re thinking about a crime scene, I’m seeing people in suits and taking pictures of things. But what does this digital forensic specialist do? What kind of background do they have?

Onur: These people usually work in national intelligence agencies, police departments, or private companies. Or they can also work independently. They usually come from a computer engineering background. So they, of course, need to know the architecture of the computer and how it works. But in Turkey, people from different professional backgrounds also serve as digital forensics experts in the courts because being recognized as an expert by the courts depends on connections made with prosecutors and judges.

And this was one of the reasons that many people were criminalized by mistake in these trials—because of the wrong digital forensics expert reports. But the people I worked with were from this computer engineering background, and they are respected figures in public. Ideally, the work they do … for example, digital data is, for us, text on the screen, like when we browse Twitter or other social media. It’s something on the screen. But for them, it is material stuff that has a “texture” that can be extracted from the computer.

So they treat it as a physical entity, and that’s why they usually liken the work to that of archaeologists because archaeologists are digging in the ground and trying to find those artifacts. So what they are doing, metaphorically, is taking that computer and trying to find or extract the data that was in the storage device.

Eshe: OK. What does it mean to track someone through their digital activity?

Onur: There are two ways. You can track in real time, which is surveillance. You can track people, for example, through wiretapping or CCTV cameras or other surveillance devices. But there is also this tracing practice that traces past digital activities. My research is mostly about the people who trace these past digital activities, not the ones who do real time surveillance.

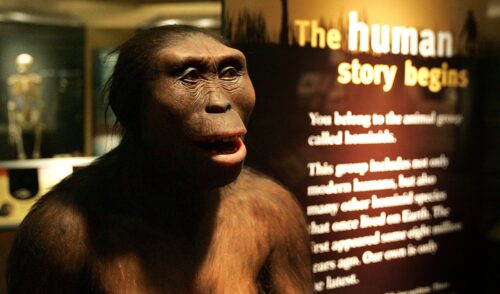

So I’m going to continue to share about digital tracing in our current context. But first, I’d like to share something that I find unique, which is that this tracing activity isn’t new. In fact, we have been doing this for thousands of years. Human beings have deciphered signs and clues that are manifested by seemingly insignificant traces. We have been tracing animals, humans, or even stars even before we used fire. For example, take a hunter who traces the footprints of an animal and imagines its size, species, maybe color, and even its whereabouts. This is a very ancient attitude and a way of knowing that shapes different scientific disciplines, like medicine, history, and forensics. So reconstructing an event through large data sets is not entirely a different practice from a hunter who traces an animal.

But there is one caveat, one different thing about digital and computational networks. Digital traces, as forensic experts call them, are not footprints; they are not exactly the result of this context of two surfaces [mimics the sound of a foot on a surface]. Rather, they are made by this network of objects and humans. And it’s not very easy to access these digital traces because they are carefully stored in sophisticated systems or high-security buildings. So there’s a difference between tracing physical entities, like footprints or fingerprints or other kinds of physical entities, and tracing digital data.

Eshe: Wow! OK. This sounds really complex on the side of the person who is doing the tracking. But I’m wondering for people who are being put on trial in these scenarios and having their digital traces used against them, how do they defend or prove their innocence? I know you’ve been following these cases. How do people try to get out of this situation?

Onur: So imagine that I am on trial, and the only substantial evidence used against me is digital metadata associated with my phone. And I have no idea how that data came to be on my gadget. One thing I can do is trace back the relevant pieces of data used as evidence and disqualify it. And this was the strategy used by the hundreds of thousands of people after the coup attempt who were accused of terrorism.

But the problem is that, of course, digital forensics practice is expensive because it requires special equipment and expertise, and not all people can access this. And there is an asymmetry between the state and the defendant. The state can access everything, like server databases or other digital data stored in, for example, web applications. We do not have the luxury to access them. And this is a worldwide problem.

In this case, the state is always too strong and can easily access everything. But in terrorism trials, some defendants became the digital forensics practitioner and let’s say the expert to defend themselves better without needing other digital forensics specialists. So they were trying to analyze their phone with their own equipment. And some of them actually managed to convince the courts that the digital data presented by the state had errors.

Eshe: And what kind of people were accused of terrorism in these trials?

Onur: Until the coup attempt, most of the people who were accused of terrorism were related to the Kurdish movement or the left opposition. The history of this counterterrorism dates back to the 1980s, and it was mostly shaped by this conflict between Kurdish guerrillas in the eastern region and the Turkish state. This changed with the coup attempt; digital traces like metadata became one of the major points of departure in terrorism trials, and people from very different political backgrounds, even supporters of President Erdoğan, were criminalized after digital data became central in these trials.

And sometimes the prosecution found out that some anarchist or some ordinary people—lawyers, teachers, people who know nothing about politics—were accused of terrorism. And I mean, of course, there were also accused people who were associated with this suspicious digital data, but they were just acquitted or released because of their connection with high-ranking state officials.

So this digital data was both powerful for the weak, for criminalizing ordinary people, but they sometimes become the lone voice when these powerful people are tried in these courts.

Eshe: We’ll hear more from Onur after the break.

[break with SAPIENS ad]

Eshe: Let’s get back to these court cases. I’m interested to know what kind of digital data was used in these trials. Can you give me an example of what you’ve seen?

Onur: One digital data used in these trials is ByLock data. So ByLock is the name of an encrypted message application, like WhatsApp or Signal. This encrypted message application is not very different from other apps, but it is thought to be more secure. Maybe. It’s debatable.

So it was active between 2014 and 2016, and the government believes that it was designed and exclusively used by members of the Fethullah Gülen movement. So the state believed that whoever accessed this application, whoever used this application, should be considered a terrorist.

Eshe: Oh, OK.

Onur: So after that moment—which [affected] more than 200,000 people—all ByLock digital traces were rendered as evidence of terrorism. And this ByLock became a taboo subject in the entire country.

Let me give you two examples. The first one is the case of an ex-military member; let’s call him Mr. K. So Mr. K was an active military member and partaking in military operations against Kurdish militants in the eastern region of the country. He was a part of this counterterror apparatus that operated against the Kurds in 2017. He did not participate in the coup attempt, but he was dismissed a couple of months later. The accusation was that his phone was connected to this ByLock application. But there were no message contents or user ID. The prosecution just identified the connection signals, and they just said that, “Your phone sent some suspicious signals to this ByLock server, and [even though] this is the only evidence we [have], you are suspicious, and that’s why we are dismissing you.”

We learned that he became a terrorism suspect because they identified some IP addresses on the ByLock server. So these IP addresses are like phone numbers. You have a phone number. I have a phone number. So these can be used as identifiers because these phone numbers are registered in our names. When we connect to the Internet, we are also using Internet protocol addresses; they are identifiers. And the judges believed that every person had a unique IP address when they connected to the Internet. And in some countries, it is like that. But in Turkey, it’s not: One IP address can be distributed to hundreds of people.

Eshe: Oh, I see.

Onur: So on the surveillance records, they saw this IP address. And this IP address was connected with Mr. K. But the same IP address actually may not [have] been connected to Mr. K; [it could have been] related to any other person. So it’s actually that the digital data is sometimes not allowing you to trace back to the individuals. So that’s one problem.

Eshe: I’m envisioning this kind of sea trawler, where they just cast this net and drag it along the ocean floor through deep waters. And maybe you’re looking for tuna, but then a whole bunch of other fish just end up getting caught in your net. That’s kind of what I’m seeing here. Does that sound right to you?

Onur: Exactly. And they’re catching whoever they can identify. And at some point, the judges were not sure if their data were correct. So I mean, there’s this belief that we can identify individuals through their digital activities; that surveillance databases can enable us to reach real individual users. But servers and databases are also filled with errors, and sometimes Internet infrastructure itself doesn’t allow us to individualize that data. It sometimes prevents us reaching the real individuals, the real users.

But they didn’t know that at the time. And that’s why they imprisoned or criminalized thousands of people by mistake. And they acknowledge that.

Eshe: I’m wondering now that you have mentioned how many people have been caught in the net, so to speak, and now that the government is seemingly recognizing that they messed up and probably incarcerated people who didn’t have anything to do with actual terrorist activity, are they working to retry cases or release people? Are these digital traces being used to get people out of that situation, given what the government is now admitting to?

Onur: So that is another problem. Yes, sometimes they were retried, and some of them got their job back, but many of them actually didn’t. And even though you are acquitted before the courts, some people remained suspicious in the eyes of the state. Sometimes, for example, there are some people who were acquitted and released, but they still cannot open a bank account. They cannot visit state institutions, for example. So even if you were acquitted, there is this invisible mark that stays on your file, and so you are always going to have a target [on your back] in the eyes of the state in some cases.

Eshe: Yeah, it sounds like it’s having a really profound effect on the social fabric of people who are getting wrapped up in this. It sounds like it drags everybody in. So I want to ask you about this ByLock application. What is wrong with using it? It sounds like if people have been found to be organizing in some way that was inappropriate or illegal on WhatsApp, I don’t know that everyone would start thinking that WhatsApp is somehow now a terrorist app. But it sounds like that’s the way ByLock is viewed in Turkey? So what is wrong with using ByLock?

Onur: So, actually, the digital forensics specialist I interviewed and worked with says that 90 percent of ByLock users were actually followers of Fethullah Gülen, but the message content they shared was prayers, daily activities, or praises for Gülen. But these messages were happening in 2014 when the Gülen movement was not that much criminalized. Some of them were representing the state. So that’s one problem because [much] of the message content doesn’t include any criminal action.

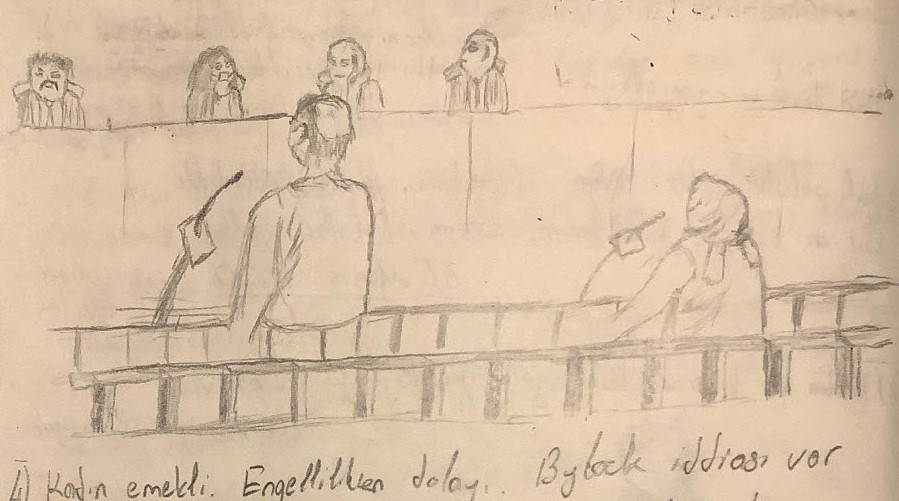

There’s one example that I will never forget. So I’m in a courtroom in Ankara, sitting on the spectator benches. Three judges and the prosecutor are looking at the computers. The room is very, very dreary, and two people in their 60s enter the room with slow and timid steps. I am expecting that one of them would come [sit] next to me, but instead both of them walk to the defendant’s dock. So the hearing starts, and I’m learning that they are a married couple and are accused of using this ByLock application. But there is one problem. The digital forensics practitioner identified only one ByLock account, and the application was downloaded and used by a mobile phone registered in the name of the wife.

But the husband claims that he was the one who used the message app because he was using his wife’s phone. And there are couple of message contents, but those were only about these prayers or these daily activities, like religious discussions, nothing related to any violent action or conspiracy. Despite that, the prosecutor becomes really, really furious. And he stands up, waves his big hands, and says that’s how the husband tries to bear the blame to protect his wife. Because forensic examiners recovered only a couple of message contents, they could not be sure who the ByLock user was based on those contents because there was not any identifiable information in those message contents.

And the judges sentenced him to seven years of imprisonment. And they just arrested him in the moments after the hearing; the police came and handcuffed him. And they sentenced the wife with a minor conviction: less than two years imprisonment. And they released her. And at the end of the hearing, the prosecutor again stood up and said to the wife, “I know you are a ByLock user, but we just let you go to look after your family.”

So, for me, this was one of the most memorable moments because I knew that these people were followers of Fethullah Gülen, although they were at the margins. I’m a person who comes from a left and secular background, and I was always critical about Fethullah Gülen’s actions and the close relationship with the state and with business circles. But the question remains, are these people terrorists, or what did they do wrong?

Because so many state officials, like high-ranking state people, government officials, including Erdoğan, had close ties with Fethullah Gülen in the 2000s. And these people—this Fethullah Gülen movement—were representing the state at some scale. At that time, following this movement was kind of motivated by these government actors. So I’m asking, “OK. Are they really terrorists?” That’s why I felt the absurdity there. In the eyes of the state and in the eyes of many people, because they have this message content, they are terrorists who must be in prison. And at that time, I was not even sure about how I should feel because the smear campaign was so strong.

Eshe: What impact has your research had on your approach to your own personal tech gadgets?

Onur: So I did this research between 2018 and 2022, and the large-scale state crackdown that took shape after the coup attempt was continuing. Groups of people were arrested almost on a weekly basis, and I regularly witnessed convictions based on digital activities. I witnessed that it was so easy to launch an investigation and adjudicate someone and to avoid criminalization of myself and my informants.

I was very careful about confidentiality of the people I work with, but I did not use these super-secure web applications and did not make efforts for extra privacy. For example, I continued to use the popular message applications that I always used, but this was because of a particular reason in the trials. The more you are careful about privacy, the more encrypted programs that you use, the more suspicion that you draw from the prosecutors.

They are seeing the secrecy; [they think] you are hiding something so now you must be a terrorist. That’s another effect … secrecy, privacy, or even using secure, encrypted message applications become suspicious in the eyes of the state. It’s not a crime, but it draws suspicion.

I like working in public places, like libraries and cafes or even on public transportation. But I had to stop that because I know a forensic examiner who was reported to the police because he was talking about this ByLock case on the phone on the bus. And someone heard him using this ByLock word and reported him to the police. Of course, nothing happened to this forensic specialist because he knew some people in the police department, but it’s possible that someone might report you to the police simply because they see this ByLock word on [your] computer or if [you] say something about it over the phone. So that’s why I have to work at home or in the courthouse.

Eshe: Oh my God. It sounds like such an intricate dance trying to prove that you’re not super private so that you can show that you don’t have anything to hide, but also never say ByLock around other people. And you do have to try to keep yourself and the people you’re working with safe. It sounds like an obstacle-filled journey for you.

Onur: Yeah, I mean, even in the messages … I was part of this telegram channel of digital forensics specialists. And they were not writing ByLock. They were writing this abbreviation. They were just writing this “B” letter. It was crazy.

Eshe: Well, you’ve shared so much here about the Turkish system, about politics, about society. You’ve done a really good job, too, of talking about how this might relate to people in other geographic locations. What is the one thing you want audiences to take away from your work?

Onur: So we usually use this Orwellian big brother metaphor. The metaphor makes us think of an overwhelming power that monitors all the people individually, you know? But surveillance and forensics based on digital technologies sometimes fail. Judges and prosecutors who I interview think that the data extracted from the phone is a window onto our everyday activities, our identity, or even our soul; for them, the cellphones speak better than us about ourselves. And this also easily disqualifies other forms of testimonies. But this trust we put onto these machines can sometimes also deceive us because it’s only one vision.

Eshe: Onur Arslan, thank you so much for talking to me.

Onur: Thank you, Eshe.

[music]

Eshe: This episode was hosted by me, Eshe Lewis, featuring reporting by Onur Arslan. Onur is a Ph.D. candidate in anthropology at the University of California, Davis. He would like to thank digital forensic specialists Toprak and Ishaan. He hopes to share their real names one day and is grateful to them for patiently training him in times of terror.

SAPIENS is produced by House of Pod. Cat Jaffee and Dennis Funk are our producers and program teachers. Dennis is also our audio editor and sound designer. Christine Weeber is our copy editor. Our executive producers are Cat Jaffee and Chip Colwell. This episode is part of the SAPIENS Public Scholars Training Fellowship program, which provides in-depth training for anthropologists in the craft of science communication and public scholarship.

SAPIENS is an editorially independent podcast funded this season by the John Templeton Foundation with the support of the University of Chicago Press and the Wenner-Gren Foundation. SAPIENS is part of the American Anthropological Association Podcast Library. Please visit SAPIENS.org to check out the additional resources in the show notes and to see all our great stories about everything human. I’m Eshe Lewis. Thank you for listening.