Why I Ask My Students to Swear in Class

“Insult me,” I tell my students.

Admittedly, my first request does not usually elicit much. The students just stare, bewildered. So I clarify, “How do your friends insult each other? ‘Don’t be a …’ ‘You’re being a little …’ ‘You’re such a …’”

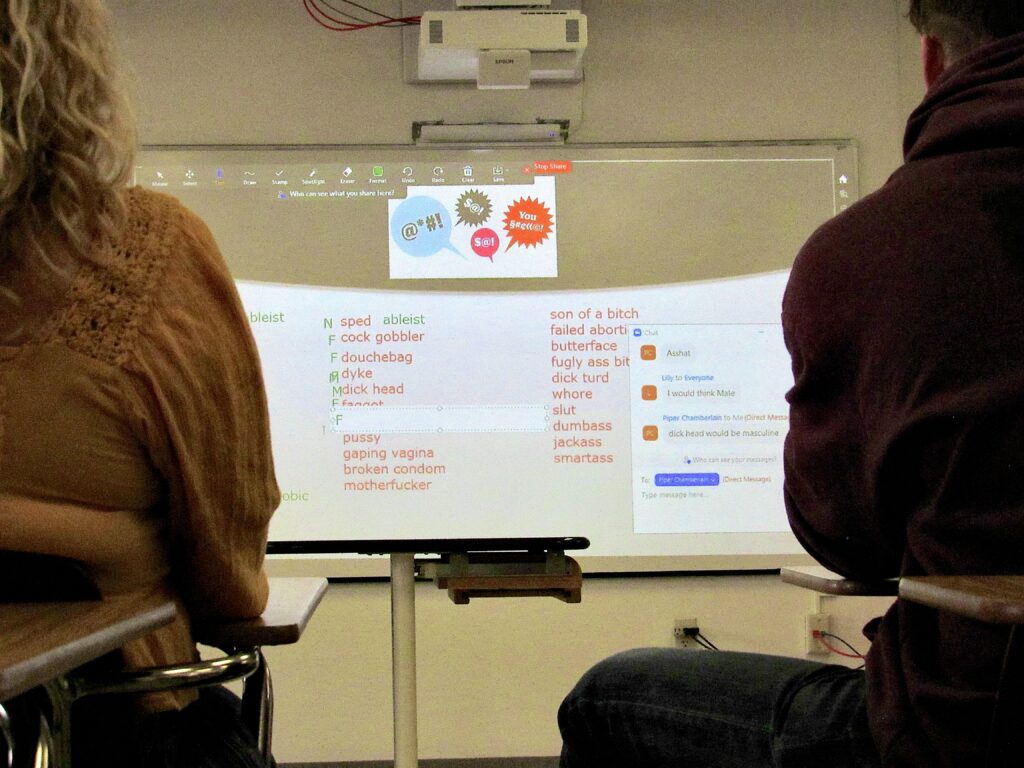

That gets them started. I assure them that they can swear, which seems to surprise some. But once someone dares to do it, the “bad words” start to flow. “Cunt!” “Bitch!” “Asshole!” “Dipshit!” I write every insult on the board until it is full.

It is subversively fun. Students seem to enjoy yelling out words that they would not typically utter during a college class. Almost every time we make this list, students who rarely participate in discussion eagerly contribute.

I repeat the words to ensure I don’t miss any, which seems to delight them. “Pussy!” “Assfuck!” “Whore!” “Slut!”

Once the students get going, it can be difficult for me to keep up.

“Motherfucker!” “Shithead!” “Douchebag!” “Bastard!”

GENDERING THE INSULTS

I am a cultural anthropologist who researches sexual and gendered violence. I teach courses in both anthropology and gender and sexuality studies. I have done this insult exercise in classes ranging from introductory courses to upper-division theory courses. The intro students seem to get the most excited about it.

“Now, what do you think we are going to do next?” I ask the students. “You guessed it: We are going to ‘gender’ them. The trick, though, is that we will not gender words according to who they are hurled at but rather why they are insulting.”

Read more from the archives on why language matters: “The Power of the Dictionary.”

Some words are easy. “Bitch” gets marked F for feminine. “Dick” gets M for masculine. “Asshole” receives N for neutral.

But other words trip students up and inspire lengthy discussions. For example, they tend to gender “douche,” “douchebag,” or “douche-canoe” as masculine.

“Why are these masculine?” I ask them.

They say these terms are usually directed at guys. “Ah,” I reply, “but that is not our goal here. We are not gendering these terms by who the insults are directed toward. Instead, think about why they are insulting.”

I give them one more hint: “What is a douche?” Often, students do not know. So, I explain that douche is a French word meaning to bathe and a product for washing out the vagina.

The students usually seem to catch on. Ultimately, we connect douching as a practice to the cultural taboos and negative connotations linked to vaginas and vulvas.

In one of my recent introductory classes, “motherfucker” sparked an intense debate. At first, students wanted to gender it as masculine. After I reminded them the exercise is about why certain words are insulting, not about who they’re aimed at, they wanted to gender it as neutral.

“Because anyone can fuck a mother!” they said.

“But that is not the insulting part,” I retorted. “Why is it insulting to ‘fuck a mother’?” It’s one of the strangest things I have ever said in a classroom setting, but the point was for them to analyze this through a gendered lens.

Two women and I tried to convince the rest of the class to put F next to “motherfucker.” Finally, a man piped up with, “Well, I have never heard someone say ‘fatherfucker,’” breaking the stalemate.

We then had a great discussion of why that term is never used, and also why we never hear the gender-inclusive term “parentfucker.” Feminist anthropologists such as Sherry Ortner and Gayle Rubin argued long ago that in the U.S. and many other societies, mothers, more than fathers, continue to occupy a social position focused on child-rearing. Because of this association, it becomes profane to even imagine them as sexual beings.

The class finally unanimously decided that “motherfucker” was indeed insulting because it was gendered feminine.

I’M LEARNING TOO

Slang changes so quickly that every year I learn something new. A few years ago, it was “fuckboy,” an updated form of “man-slut” or “man-whore”—two terms that often appear during the insult exercise alongside regular old “slut” and “whore.” All four terms are gendered feminine; even with “man-” tacked on as a qualifier, “slut” and “whore” are always associated with shaming women for their sexuality and bodies. In contrast, “fuckboy” almost seems like a variation on “player,” which could be used as either an insult or a compliment.

Last year, the new word was “sus.” I admit I did not understand it right away, and the students had a hard time explaining. One student, Kyle Hunteman, sent me more information after class upon my request. He did such an excellent job that I understood the term right away; see his explanation in the following insert. “Sus,” as Kyle explains it, hits all the points that I want to make with this exercise.

THE POWER OF GENDERED INSULTS

Once the class has gendered all the terms, we make a tally. Recently, more gender-neutral terms have made the list, but the tally always includes more feminine terms than masculine ones. I ask students point blank: “Why did I have y’all do this? What is the purpose?”

They easily point out the difference in tallies between masculine and feminine words.

“So what does that tell us?” I prod. This can be trickier for them to answer.

In my introductory courses, I find it helpful to pair this exercise with anthropologist James Armstrong’s “Homophobic Slang as Coercive Discourse Among College Students.” Armstrong’s piece has two main points: Using homophobic slang promotes an uncritical acceptance of homophobia, and it reinforces masculine dominance by confirming masculine values while degrading feminine ones.

We discuss Armstrong’s piece before we do the insult exercise; it was first published in 1997, and it shows. The terms that concerned Armstrong—“homo,” “fag,” “gay,” and “queer”—rarely show up in our present-day insult exercise.

But the takeaway is the same. Combined, the piece and the exercise help students understand that language changes, but femininity is consistently perceived as insulting and degrading.

Insults matter. The words we use in our everyday speech often degrade certain groups of people disproportionately—even if that’s not our intention. Achieving gender equality remains a distant goal, in language or anywhere else, but it starts with recognizing these patterns. My students, at least, can leave my classroom with a new perspective on an old problem.