Unsung Native Collaborators in Anthropology

Growing up a Brown girl and aspiring anthropologist, my idea of success was represented by a gallery full of White scholars. It was in the stern face of U.S. anthropologist Margaret Mead, braving her way across the Pacific Ocean on route to Samoa. It was in cultural anthropologist Clifford Geertz’s crazy hair, flailing as he ran away from the Balinese cops who raided an illegal cockfight he took part in.

Flipping through the browned pages of a history of anthropology book in college, I could not find any mention of a non-White ethnographer. The book focused only on the founding figures, making it sound like they built anthropology singlehandedly with just their own intellect, perseverance, pens, and notebooks.

The careers of iconic anthropologists are well-documented. But for many anthropologists, research involves the meticulous labor of translators, cultural interpreters, and research assistants who help them understand the world better. And very little is known about these collaborators of color who helped make anthropologists’ research successful.

Not many recognize the name Ali bin Usmus, a Javanese collaborator who U.S. anthropologist Cora Du Bois called a protector, mentor, and friend. Few are familiar with Muchona “the Hornet,” a man with unparalleled knowledge of Ndembu medicine plants and rituals who served as Scottish anthropologist Victor Turner’s “interpreter of religion” in Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia).

Despite their significant contributions, people like bin Usmus and Muchona are still regarded as insignificant figures.

As an Indonesian anthropologist-in-training trying to find my place in history, I ask: Who stood behind the success of famous White anthropologists? And how did those people contribute to these researchers’ achievements?

The archival work I conducted for my research project in 2021 led me to investigate the lives and contributions of native research partners who worked for the United States’ most celebrated anthropologists: Franz Boas and Margaret Mead. Tucked between footnotes and piles of archives, the names George Hunt and I Madé Kalér might not be as star-studded as their employers’, but they contributed tremendously to the world’s anthropological knowledge.

This essay is a refusal of their forgetting.

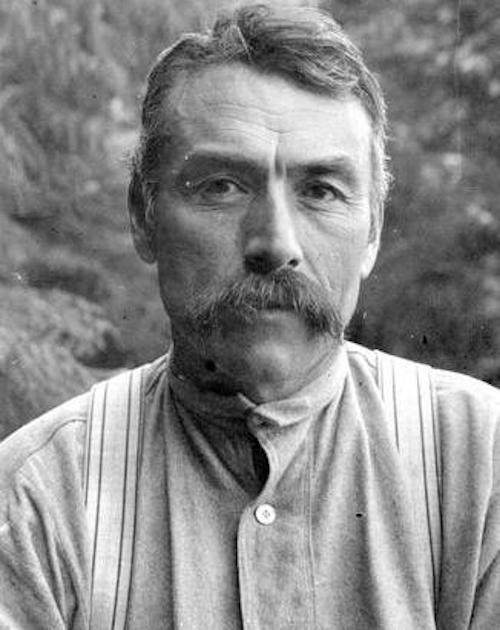

George Hunt And Franz Boas

George Hunt was Boas’ Indigenous field agent and interlocutor in the U.S. Pacific Northwest, and Boas often called him his “dear friend.” Born in 1854 in Fort Rupert, British Columbia, Canada, Hunt was raised by an English father and a Tlingit mother. Due to this bicultural upbringing, he was often employed as an interpreter by White scholars and collectors who visited the area. Hunt started his collaboration with Boas in 1886 as a part of the Jesup North Pacific Expedition, a major anthropological exploration of the relationships between cultures in the Pacific Northwest and in Siberia, Manchuria, and Sakhalin Island in Russia.

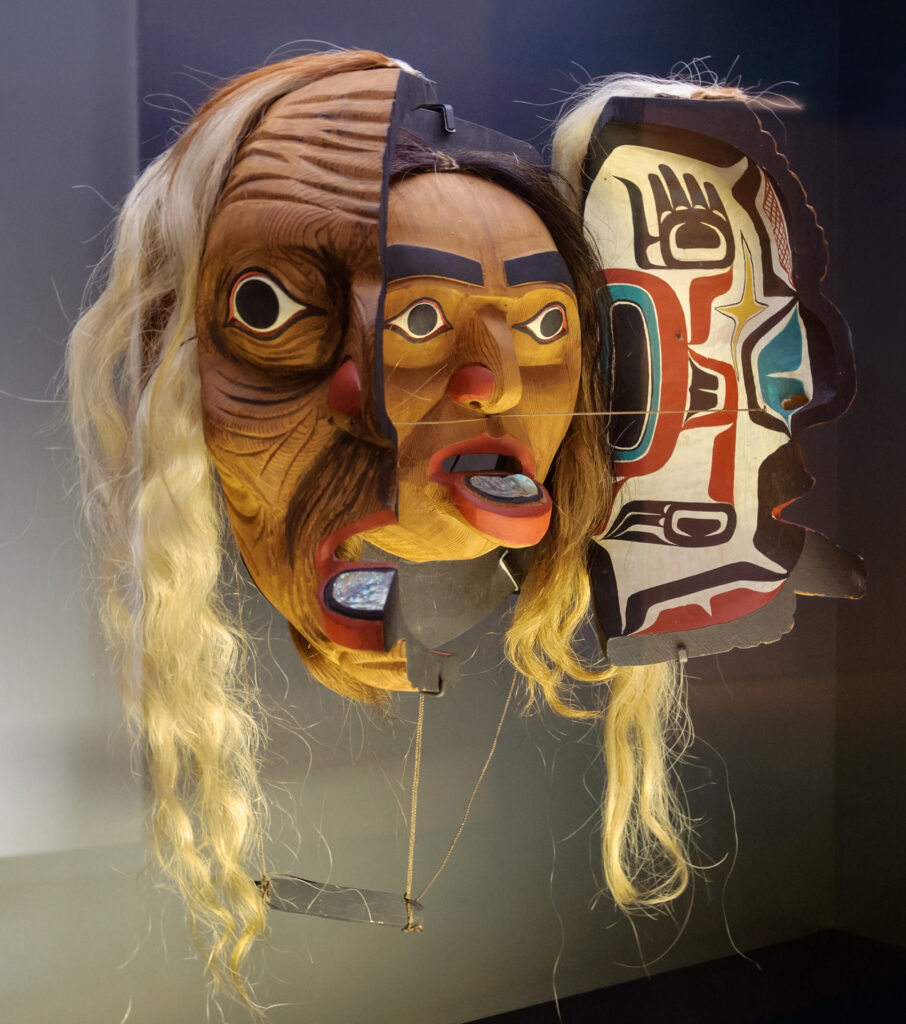

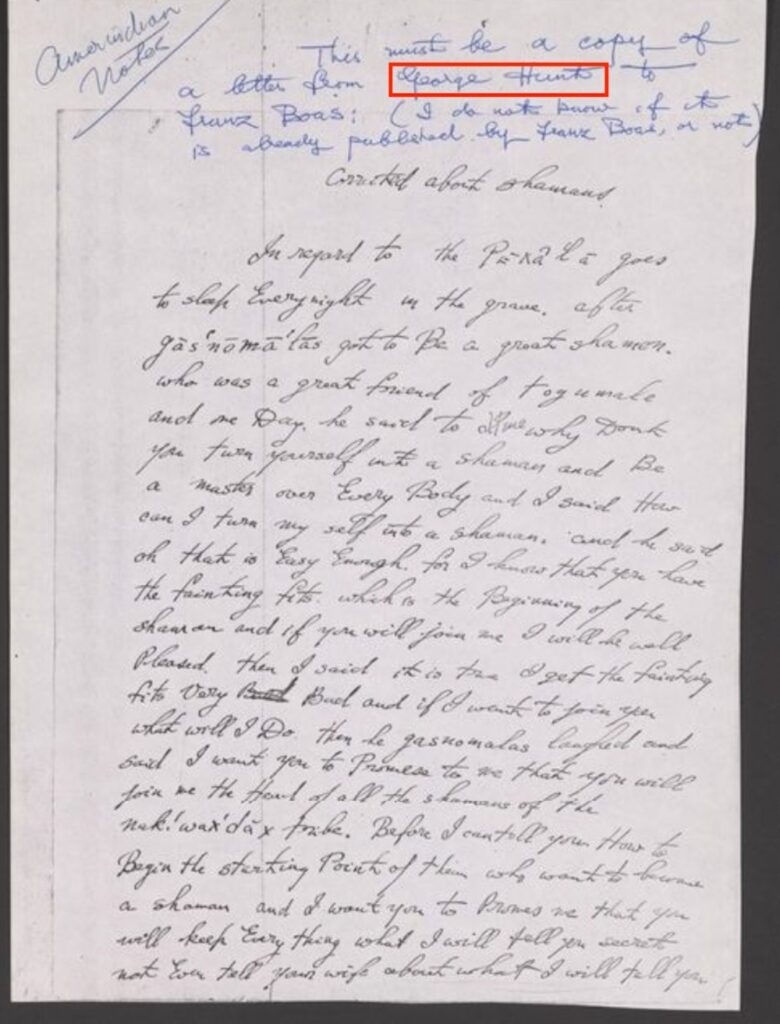

Hunt’s main responsibilities were collecting artifacts and information about the Kwakwa̲ka̲’wakw, an Indigenous people in the Pacific Northwest. He wrote about the tribe’s customs and rituals, and mailed most of his notes to Boas, who lived mainly on the East Coast. Hunt produced tens of thousands of handwritten documents on the topics of Kwakwa̲ka̲’wakw activities, oral histories, and sacred practices.

Nonetheless, Hunt’s role encompassed much more than data collection. As anthropologists Charles Briggs and Richard Bauman wrote, Hunt also served as an important mediator who voiced Boas’ words to the Kwakwa̲ka̲’wakw. For example, during a Kwakwa̲ka̲’wakw feast ceremony—involving platters of salmon and barrels of berries drizzled with fish oil—Hunt translated the speeches and explained the ritual to Boas. Isaiah Wilner, a historian of knowledge, argues that Hunt not only provided information to Boas, he also built a healthy, trusting relationship between the anthropologist and the Kwakwa̲ka̲’wakw community.

Just as Boas relied on help from his unsung interpreter, Hunt relied on others for information: Indigenous women, whose contributions are continually overlooked. As anthropologist Margaret Bruchac has extensively chronicled, Hunt was surrounded by Indigenous noblewomen. His mother was born to a noble Tlingit family, and his two wives were high-ranking Kwakwa̲ka̲’wakw women.

Although Hunt never identified himself as a Kwakwa̲ka̲’wakw—the community even referred to him as a “foreign Indian”—his wives’ status exposed him to the knowledge of the elite. He got most of his information about Indigenous food preparation and sacred marriage rites from his high-ranking wives. When his first wife, Lucy Homikanis, died, he wrote to Boas: “This is about the hardest thing I ever got. That is to lose my dear loving wife. Who was a great help to both you and me in the work I have to do for you.”

Despite the close collaboration between Boas and Hunt, the power imbalance between the two often resulted in conflicts. According to Wilner, Boas tried to manipulate Hunt’s financial condition several times, including lowering his pay from 50 cents to 20 cents for a page of field notes. Upset about this treatment, Hunt protested by writing on smaller script paper so he could be paid more.

Boas also put Hunt in dangerous situations by constantly requesting new materials that were often difficult to access. One time, Boas encouraged Hunt to enter Indigenous burial sites and collect skeletal remains from the pre-colonization era, along with art that was “free of Western influence.” These examples reflect that no matter how integral Hunt’s contribution was to Boas’ research, Hunt’s position in their relationship remained precarious.

I Madé Kalér and Margaret Mead

Years later, a young Balinese man named I Madé Kalér worked as a secretary for Margaret Mead, a superstar anthropologist who was Boas’ student. Madé Kalér was born in the 1910s to a lower-caste family from the mountains of North Bali. Well-educated in Malay and Dutch schools, he grew up speaking five languages, including English, Dutch, and Balinese.

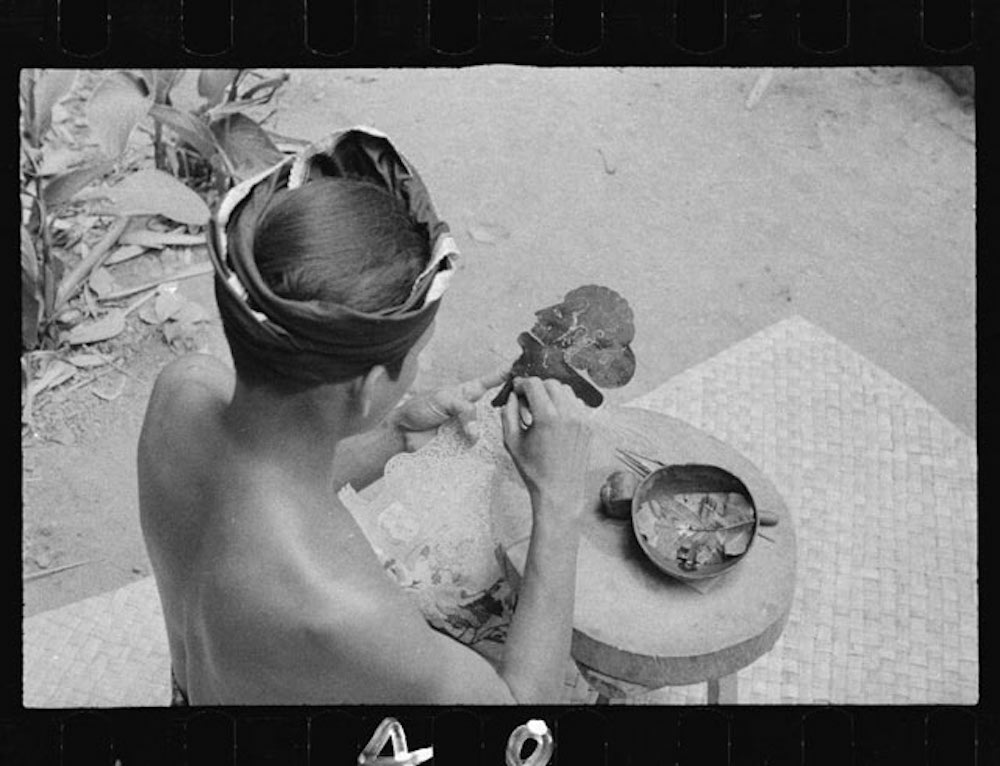

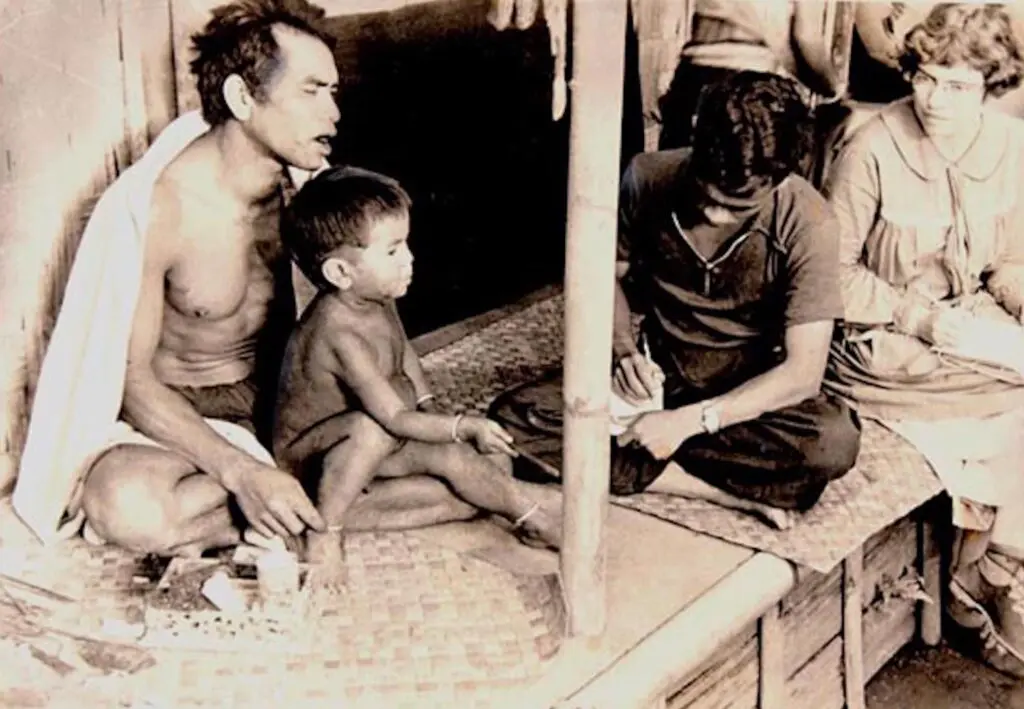

After graduating from high school, he traveled to Batavia (now Jakarta), the capital of the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia). He was hoping to find a well-paying government job. Instead, he met Mead and her husband, Gregory Bateson, who were looking for a research assistant for their fieldwork in Bali—studying character formation and how it related to schizophrenic behaviors. That eventful encounter in 1936 was the beginning of their collaboration.

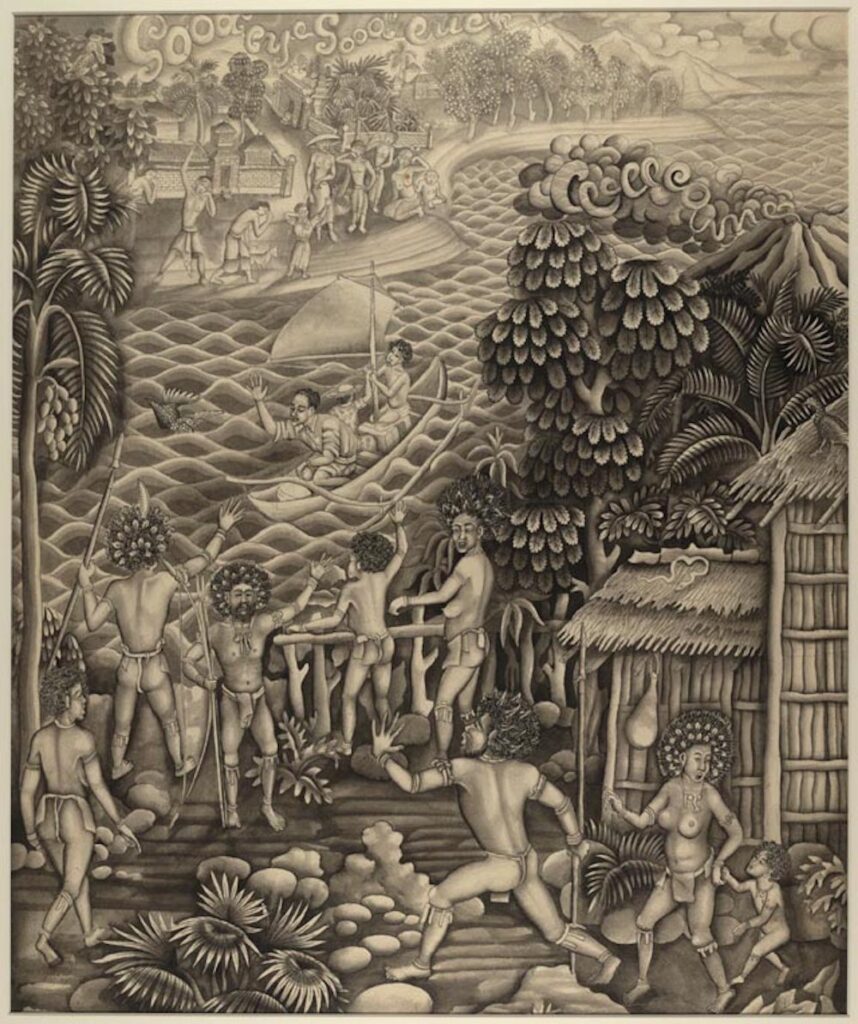

Madé Kalér might only be mentioned briefly in Mead’s work, but he wrote more than 500 Balinese texts to supplement Mead’s notes. He covered a plethora of Balinese customs, such as a baby’s 3-month birthday and a village’s purification ritual. Madé Kalér’s fluency in Balinese made him sensitive to the unseen and spontaneous. His observations captured the sadness in a lower-caste family’s funeral ceremony, children’s dreamy banter about their future professions, and ceremonial details. These insights often escaped Mead’s attention due to the language barrier.

Madé Kalér also turned his family members into informants and creatively delved into his own boyhood memories as a source of data. This approach was fresh and enriching to Mead’s work, especially since previous research on Balinese culture prioritized high-caste male adults as sources of information.

The fact that he worked for Mead did not stop Madé Kalér from disagreeing with her observations. For example, he wrote, “I hear a crying. It was I Reta, the same child from earlier. I Nyonyah [Mead] said that [the child] was hit on the head by his mother. Whether that was true I do not know. Once a child was able to crawl that would not be allowed in Bayung.”

Since Madé Kalér stayed with Mead during their research, he was involved in various domestic work that helped the fieldwork go smoothly. He picked up the couple when they first arrived in Bali, kept calendar records of coming events, and trimmed the lamp wicks. He sometimes took care of Mead’s household bookkeeping and translated English documents into Dutch or Malay, since Mead spoke neither language.

Interestingly, Madé Kalér also hid some information from the anthropologists. As he explained in an interview 50 years after the fieldwork, Mead and Bateson tended to see Bali through rose-tinted glasses. They had very little awareness of caste politics and pauperization among rural Balinese—both linked to broken colonial policies. Madé Kalér decided not to tell them this “ugly truth” to protect himself and his employers from the Dutch colonists’ watching eyes. Dutch spies would not hesitate to interrogate anyone who engaged in politically suspicious activities, including expressing negative sentiments about the colonial government’s policies in Bali.

As hardworking and brilliant as he was, Madé Kalér refused Mead’s offer to work with her abroad. He chose to stay in Bali and eventually found a job as an elementary school teacher—a position he thoroughly enjoyed until his retirement.

Although he might not be defined as a “scholar” in the Western sense of the word, his reputation as the Balinese native informant was well-known among American academics who came to study the island’s culture. In her last letter before her death in 1978, Mead wrote fondly to Madé Kalér, “If someone could find them a secretary like you were in 1936, they would be very fortunate!”

Boas and Mead remain two of history’s most impactful anthropologists, but they did not create knowledge single-handedly. The often-unacknowledged labors of their local research collaborators facilitated the birth of their prominent work and academic success. These collaborators’ initiative, cultural and political awareness, and hard work made them intellectuals in their own right.

The stories of Hunt and Madé Kalér show that anthropology was—and always will be—an intercultural and collaborative effort. Whenever people pick an anthropology book from a shelf, I hope they can pause and ask: Who are the invisible co-creators of this work?