Writing Indigenous Oral Tradition to Fight a Dam

As villagers and our group of researchers walked along the Apayao River, Lakay (Elder) Warling Maludon pointed out the parts of his hometown that will likely soon be underwater. Like many Isnag people, the 75-year-old has lived all of his life in this river valley in Kabugao, Philippines. The Isnag are an Indigenous community called “river people,” and their name means “from the interior”—the interior of the river.

The Isnag’s lifeways center on this body of water weaving through forested mountains. To some, it is a source of identity, a sacred site for traditional ceremonies, the home of spirits who watch over their people, and the inspiration for art, songs, and dances. It provides fish for food, water for farming, and a place of leisure for children and adults alike.

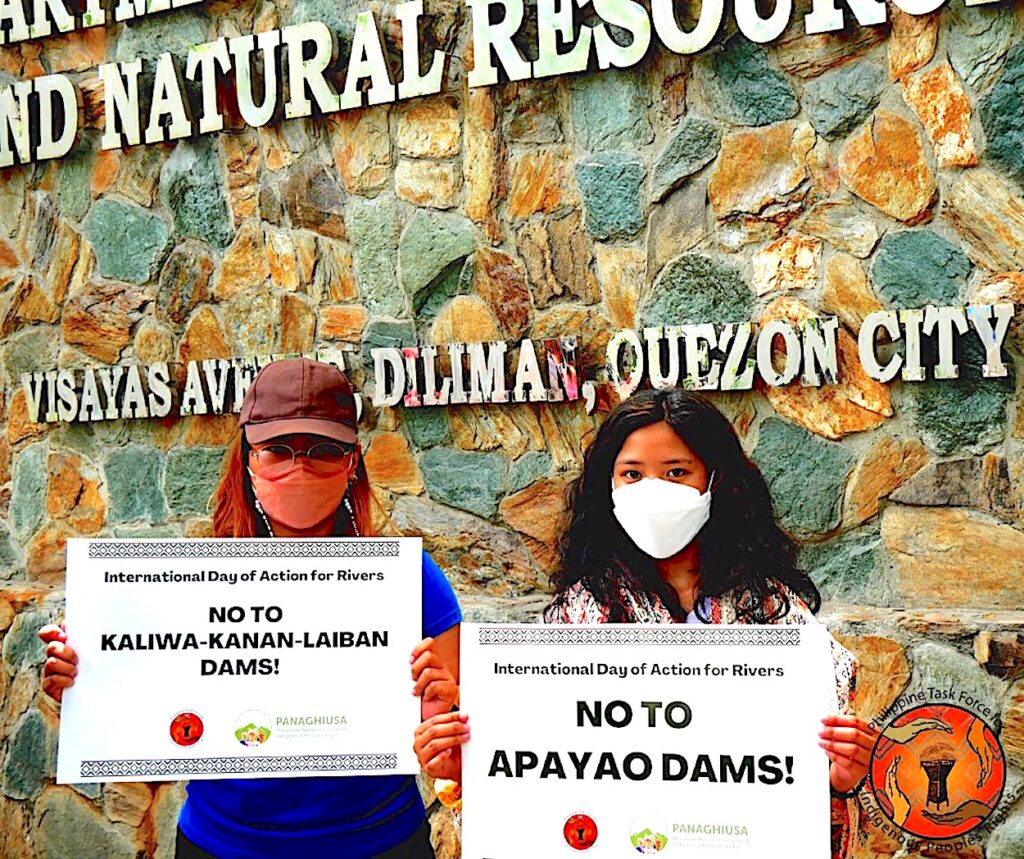

But many people see this river as a prospective source of electricity and money. The Pan Pacific Renewable Power Philippines Corporation is planning to construct four megadams to generate power from the Apayao River to supply electricity to various parts of the Philippines. The Aoan and Calanasan dams will drive some Isnag communities out of their territories, while the Gened 1 and 2 dams will submerge Isnag villages and sacred burial grounds. As of now, there is no plan to relocate the Isnag communities.

As we walked near the site of a proposed hydroelectric plant, Lakay Warling bemoaned the fact that his people have to choose between protecting their ancestral domains and leaving in exchange for compensation. “What some of us don’t understand,” he lamented, “is that money is temporary. Once it is gone, it is gone.” When that happens, the Isnag will have lost their money, their river, and their ancestral home.

What they won’t lose, Lakay Warling hopes, is their history and culture. That’s because the Isnag are engaging in an act of cultural resistance: They are writing down their Oral History.

Many Indigenous people view written documentation as a threat to the sacredness and privacy of oral culture. But the Isnag have made this contentious and challenging decision in a last-ditch effort to protect their lifeways and prove their ownership of the land in the legal battle against the dams.

While working with the Isnag, I have become fascinated by the community’s collective resistance. As a community worker engaged in the anthropology of development and an Indigenous woman from another part of the Philippines, I am curious about the ways Indigenous peoples pursue their right to self-determination.

Threatened with destruction, generations of Isnag people are joining forces and finding new ways to safeguard their traditions and land. It’s a compelling case of what Indigenous scholar Gerald Vizenor called “survivance”—not just surviving but creating a story of active presence through resistance.

THE DAMMING HISTORY OF THE PHILIPPINES

Since the United States recognized the Philippines as a sovereign nation in 1946, corporate and state-sponsored development projects have repeatedly destroyed Indigenous territories throughout the archipelago. This is an especially painful reality in a nation internationally hailed for being among the first to recognize the rights of Indigenous peoples through legislation.

In 1997, the Congress of the Philippines passed the Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act (IPRA), which enshrines Indigenous rights to self-governance and ownership of lands they have occupied since time immemorial. One salient feature of the law is the right to free, prior, and informed consent. This provision empowers Indigenous peoples to make collective decisions on projects and programs concerning their domains.

However, extractive industries have found ways to legalize encroachments on Indigenous lands in the Philippines by presenting a “certification precondition” that claims communities have given consent. In some instances, these organizations have allegedly secured the certificates through unscrupulous means.

According to sworn statements, some Isnag people say they were coerced into signing forms offering consent to the Gened dams or were misinformed about the content of the forms. Lakay Warling and other Isnag elders attest that in one of the government-facilitated consultations, the commission pre-selected the participants and barred others from attending, effectively disenfranchising many Isnag people.

Some Isnag have filed cases against the government agents involved, and the community has formally expressed non-consent to the Gened dams. Still, the project seems certain to push through because, as the government has argued during consultations in Kabugao, the corporation complied with the IPRA’s requirements.

In addition, though the dam company has offered compensation in exchange for pushing the community off their ancestral lands, only selected families qualify for remuneration. Moreover, the amount is based on the area of land indicated in the land title, and most Isnag lands are not titled.

“Here in Waga, less than half of the households will be compensated,” Lakay Warling explained. “In Bulu, the neighboring village, only one family will be paid. We will be just like those who lost their lands because of Ambuklao.”

The Ambuklao dam was one of the first megadams constructed in the northern Philippines in the mid-1950s. The hydropower project displaced Indigenous peoples and prevented them from sustaining their work of rice farming. Not all communities that were promised compensation received what was duly theirs. And despite the dam’s promise of generating energy, the displaced communities weren’t hooked up to the electrical grid until 50 years later.

In spite of standards such as the IPRA and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, state-sanctioned development projects like the Ambuklao and Gened dams show how Indigenous territories are often reduced to mere resources that can be exploited under the guise of progress.

But these projects have also become an impetus for Indigenous communities to come together to resist the destruction of their lifeways and to pursue the right to self-determination.

RESISTANCE THROUGH WRITING ORAL TRADITIONS

After our group took a boat to Lakay Warling’s family home, he lit up the stove to boil coffee. While we waited, Ot-ot, a young Isnag man who is co-leading the community struggle, talked about the importance of Oral Traditions. “Our ad-adodit (Traditional Stories) carry the wisdom of our ancestors,” he says.

Through storytelling, Isnag people transmit knowledge about their traditional lifeways, including the management and protection of resources, sustainable foodways, leadership and governance systems, health and wellness practices, and material technologies. For example, the Isnag engage in a mourning ritual and conservation practice called lapat—a time period when people cannot fish or fell trees, which allows the river and forest to regenerate. At the end of lapat, they catch fish to serve at ceremonies.

However, the erasure of Isnag territories due to the dams would bring with it the erasure of their histories—and their erasure from history. There is scant literature about the Isnag’s lifeways, and the few published documents are mostly written by scholars outside Isnag culture.

“We don’t have written materials about it in our community or school libraries,” Ot-ot says, adding that this has resulted in the younger generation’s “waning of knowledge” about Isnag traditions. “Ironically, we have a rich Oral Tradition with many stories about the river and our people,” he adds. “We need to record these, or else we risk losing bodies of knowledge.”

Ot-ot explained that writing down Isnag Oral Traditions could help establish their ownership of their land while defying the threats of extractive industries. Under Philippine law, documenting their history may lend support to their claims over their territories. Philippine law recognizes Oral Tradition as one of the important poles of Indigenous cultures. It is considered proof of Indigenous peoples’ long-standing connection to their lands, which is necessary for the state to recognize their land claims as legitimate.

However, under the law, Oral Tradition cannot stand on its own. It must be complemented by other elements of Indigenous culture, such as customary justice systems, kinship systems, folklore, and material culture. For example, if Oral Histories reference belongings or landscapes associated with particular time periods, the community must look for supporting evidence such as archaeological objects.

The catch is that, in order to be legally recognized, Oral Tradition must be documented and presented to the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples. It is therefore important who writes the Oral Tradition and why.

Ot-ot explained that some pro-dam community members have sent the commission a version of Isnag Oral Tradition that was not validated by the community. This concerns Ot-ot, Lakay Warling, and their anti-dam allies, who constitute the majority of the population in the region. They worry the pro-dam version of Isnag history will downplay or dispute the centrality of the Apayao River to the community.

Even apart from disputes over the dams, determining how to write down Oral Traditions is no easy task. The written word can affect the integrity of spoken traditions and the experience of learning communally. Oral Tradition involves relationship-building through interactive listening. It consists of movements and gestures laden with meaning that written words cannot capture.

In addition, written history is often told from one perspective, so it can be limiting compared to storytelling and discussions that take place in a community setting. Oral Tradition tends to be fluid, whereas writing down oral customs tends to freeze them in time, hindering people’s ability to change them in different contexts.

Furthermore, some Indigenous elders argue that not everything in their culture should be shared with people outside their community because it would diminish the sacredness of their practices. Once something is written down, they fear, it would be exposed to the general public.

To determine the best way to document their oral culture, Ot-ot and other Isnag youth leaders organized a magdudungu—the Isnag community practice of gathering over food and sharing stories—with Lakay Warling and other elders. The magdudungu helped convince some community members that writing down Oral Traditions is not meant to replace traditional ways of knowledge transmission; rather, it is intended to reinforce them in the face of threats by development.

As a result of these discussions, the Isnag documented their ad-adodit (Oral Stories), songs, traditional recipes, and more. Ot-ot says the magdudungu became an educational space for the younger generation, many of whom are now eager to learn more about how their ancestors lived and to help sustain their own Isnag identity. The magdudungu also put a premium on the Isnag’s agency, providing a space for collective resistance to the oppressive structures and conditions that disenfranchise, dispossess, and discriminate against Indigenous peoples.

As we enjoyed our coffee, Ot-ot and Lakay Warling exchanged recollections of the Apayao River and its meanings to the Isnag. Lakay Warling heaved a sigh of relief that, despite the threats to their cultural survival, generations of Isnag were uniting against the dam project.

“Will you continue to fight the dams even though you know that the construction is impending?” I asked.

“Yes,” Lakay Warling replied. “We are doing this not just for those of us alive today. It is for the generations yet unborn and the generations who’ve left us. We will continue resisting even if the government also continues to tell us to leave.”

I shifted my gaze to Ot-ot, who was in quiet contemplation. As I was about to sip more coffee, I realized my cup had no more. I’d wondered where the bitter aftertaste was coming from.

We ate lunch silently. Perhaps we were searching for words to capture the ambivalence we had felt since morning. If there is any comfort in this silence, it is that this community’s struggle goes on, showing that Indigenous peoples, when pushed to the limits, will do what it takes for survivance.