The Double Lives of Chinese Foreign Correspondents

In 2015, I sat over coffee at a London cafe with a local correspondent of China Central Television (CCTV), the main state broadcaster. Over the preceding years, I had talked to many Chinese foreign correspondents. Some had become lasting friends; others treated me with hostility, suspecting me of planning a Western denunciation of Chinese media. But this particular encounter was unusually awkward and unpleasant. In the course of an initially friendly discussion, my interlocutor commented disapprovingly on a BBC correspondent’s attempt to interview a Chinese human rights lawyer who was under house arrest. Gradually, she worked herself into a fury that turned into a violent denunciation of the lawyer as a traitor to his country.

As an anthropologist, I have spent decades studying newly mobile Chinese elites, like entrepreneurs and corporate managers, who have likewise made their way out into the wider world. In 2013, I set out to study the lives and work of Chinese foreign correspondents, whose numbers have been expanding rapidly due to a government effort to “make China’s voice heard in the world.” (Western media’s foreign correspondent networks, in contrast, have been shrinking in the face of tightening budgets.)

I wondered how this expanding force of journalists, often asked to report “from a Chinese perspective,” lived and worked in societies very different from China’s. Although it is generally thought to be difficult to gain access to Chinese media organizations, I found enough correspondents who were willing to talk to me. Of course, they were also uncommonly articulate and skilled at shaping their stories the way they wanted. Perhaps more than in most anthropological fieldwork, I ended up discussing rather than just listening to my interlocutors’ views.

China is one of the few countries that has never experienced a democratic government, and its authoritarian rule seems increasingly robust. The last time the Communist Party relaxed its control over society was in the 1980s, and that ended with a democracy movement that was violently crushed in Tiananmen Square in 1989. The practice of investigative journalism in China experienced a brief heyday in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when the media gave risky scoops by intrepid reporters some room in order to gain audiences. But that experiment soon ended, and investigative journalism has been on the decline ever since.

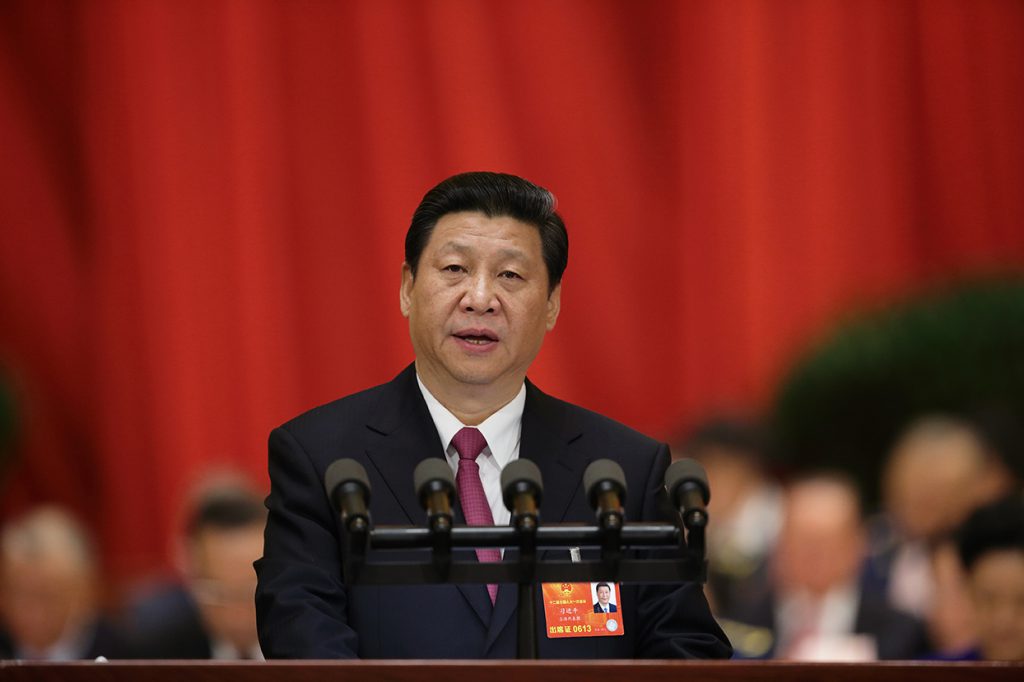

The current chairman, Xi Jinping, who took power in 2012, enjoys more popular support than his less hard-line predecessors. He has cracked down more severely on dissent and revived long-abandoned practices, such as televised confessions by jailed dissidents and proclamations of loyalty by academics. In a highly publicized 2016 speech that has been compared to one by Mao Zedong, Xi reminded journalists and other “culture workers” that their loyalty to the Communist Party should come before everything else.

Given all this, what do young Chinese correspondents want to tell their audiences, I wondered. How do they handle political expectations, censorship, and changing economies? Do they see themselves as flag bearers for China’s expanding global influence, or do they have other goals in mind?

From the beginning of my fieldwork, I knew that not all the reporters I met would turn out to be either “hacks” blindly parroting the views of the Chinese government or “rebels” fighting against censorship to publish unbiased investigative reports. But I was not quite prepared for the contradictions I found in more than 70 interviews with Chinese journalists acting as foreign correspondents on four continents. Over the course of four years of research, I met Western-trained Chinese journalists who cultivated worldly wise, cosmopolitan personas and Oxbridge accents; at the same time, they were critical of Chinese media conditions and embraced the goal of journalistic professionalism. Yet these same people often produced one-sided, propagandistic journalism that put forward the Chinese state’s view of the world.

This does not bode well for journalism, not just in China but around the world.

Peter was one of the few correspondents dispatched by a market-oriented rather than a directly state-financed media organization in China. [1] [1] To protect people’s identities, all names in this piece (other than the author’s) are pseudonyms. His publisher ran a financial news portal and several economics magazines, and had sent Peter to cover the European economy. On his desk sat a photo of Alistair Cooke, the legendary BBC correspondent whose radio series Letter From America was broadcast for 58 years. For Peter, Cooke captured the essence of the foreign correspondent: someone who intimately knows the society he covers but always retains an outsider’s view.

Media outlets identified with more liberal positions have been under increasing political pressure in China.

Peter, then in his late 20s, was politically liberal and had a universalistic view of journalistic professionalism that had been developed under the tutelage of professors at a top journalism school in China. He was critical of the Chinese government’s authoritarianism and believed that the media’s role is to inform readers through in-depth, unbiased reporting. He was neither expected to be nor interested in being “China’s voice.” But he had little opportunity for what he most wanted to do: investigative reporting. He did a few in-depth stories that were recognized in the profession for their quality, including a piece on the reasons for a Chinese company’s failure to build a road in Poland and another on a price-fixing case against Chinese vitamin makers in a U.S. court. He spent a month researching the Poland story, which was also published in English and received a prize in Britain. But that experience was exceptional. Usually, there was no time, money, or room for such stories.

Peter’s media organization, considered liberal in China, gave him more freedom than most others to go after the stories he wanted. But the limitations created by economic and political pressures still frustrated him. Media outlets identified with more liberal positions have been under increasing political pressure in China. The flagship of these media, the newspaper Southern Weekend, underwent a change in editorial leadership and was saddled with internal censors after a 2013 staff protest against censoring an editorial. It has since then lost both its boldness and its top journalists. At the same time, advertisers have moved their money to mobile content providers, circumventing media companies and draining the coffers at media outlets. Pressure in the surviving semi-independent media is immense. For Peter, this meant “pressure to generate stories immediately” and an inability to get quick approvals to move around within his host country to chase stories.

In many ways, Peter’s struggles were not unlike those of his European or North American peers, who also face a reduction in advertising dollars and pressure to churn out quick stories rather than investing in long-term investigations. But Peter faced the additional problems of lower pay and greater political vulnerability. In the three years after I first met him, Peter was transferred twice, and he finally quit to join a European broadcaster.

John, another foreign correspondent in his late 20s, had studied at two elite British universities, but he did not share Peter’s liberal values. “Pál,” he protested in his impeccable Oxbridge accent, “you are just looking for those things you want to hear. You think we should look at China critically, and then we are okay.” An Africa correspondent for China’s national English-language daily, John resented being typecast as the party hack, in opposition to “independent minds” like Peter who populate the liberal Chinese press. John wanted me to accept official media journalists on their own terms, rather than comparing them to some idealized vision of warriors for the truth. He saw journalists like himself as essentially no different from those at the BBC: professionals in the service of some news agenda or other.

His experience in the West, John said, had disabused him of liberal journalistic ideals: He concluded that all media were biased (a frequent refrain among Chinese journalists). Since everyone has a bias, in his view, it was only natural for China’s state media to promote the government’s agenda. Yet he also said he believed in professionalism and “hated propaganda,” dismissing political constraints as an excuse for poor journalism. For him, being a professional journalist and serving a state agenda were not irreconcilable. If he had doubts, he kept them to himself.

Zhang Gang, a rising star with CCTV, was somewhat more forthcoming about his doubts. Despite his youth—he had been Peter’s college classmate—Zhang was already a chief correspondent in Washington, D.C., the network’s most important overseas bureau. He frequently appeared on screen, not only on CCTV but also on Russia’s English-language news channel, RT, and on other channels, where he was sometimes asked to present China’s view on foreign affairs issues. He clearly relished being “China’s voice”; he told me he would like to be a press secretary to a Chinese leader someday.

Yet every now and then, Zhang let slip a remark that suggested he may be more conflicted about his position than he let on. “I’ve been here so long I sometimes forget why I am not happy,” he told me, referring to CCTV rather than the U.S. Zhang felt strongly about strengthening a “Chinese voice in international news.” At the same time, he appreciated what he called “progressive journalism,” something he associated with the liberal wing in China that has, in the past, angered the government.

Despite their youth, Peter, John, and Zhang Gang are already considered senior journalists in the world of correspondents from China. This is not only because many correspondents are in their mid-twenties but also because turnover is high. Many leave for higher-paying corporate jobs; some resign in disappointment. One young correspondent I met from the news agency Xinhua, for example, remembered being initially excited about her posting in India, where she was keen to cover politics in the “world’s largest democracy.” But her employers consistently pulled her back from the stories she wanted to write: She was neither to “go overboard” in covering democratic politics nor to harm Chinese-Indian relations through negative coverage. Gradually, she stopped taking initiative. After a year, she quit.

The globalization of the Chinese economy has thrown many Chinese into direct contact with the world. Today more young Chinese professionals engage with the world than ever before, while serving or depending on an increasingly nationalistic and authoritarian state. Although they are at ease in the world, their professional and social lives rarely cross those of foreign colleagues—the short leash of their increasingly repressive paymasters sets them apart.

If the lives of Chinese journalists abroad are anything to go by, young Chinese expatriates will have to live with the contradictions of cosmopolitan lives and nation-centered careers.

This worries me. The tight rein of Chinese authoritarian rule over the country’s foreign correspondents means that reasoned discussion of different viewpoints is scarce even within organizations that have the ability to resist economic pressures that traditional media everywhere face. And many of the people involved—intelligent, educated people like John—are either blind to this situation or see it as morally acceptable. I do not. And this phenomenon may spread. Leaders who disregard the principles of liberal democracy are gaining footholds around the world, from the Philippines and Hungary to India and the United States. Journalism around the world may follow China’s example. We should be wary and perhaps learn something from those struggling with these contradictions today.