Collaborating So a 200-Year-Old Pipe Can Continue Its Work

A PIPE’S HOMECOMING

In November of 2022, a small ceremony unfolded just outside the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM). Drums, song, smoke, speeches, and tears—a 200-year-old pipe was returning to its ancestral home.

The ceremony marked a repatriation. Yet it was also something different.

For 40 years, ROM has been repatriating objects and Ancestral remains from its collections to descendent communities across Canada. Although much more work needs to be done at ROM and other museums, wampum belts are coming back to their keepers, medicine masks are once again at work in their communities, and the souls of many disturbed Ancestors are finally at peace.

The pipe repatriation in November was different because ROM bought the pipe to give it away.

With federal funds, ROM purchased the pipe in 2020 from a private seller on behalf of Anishinabek, led by Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory, one of the First Nations of Manitoulin Island, where the pipe was made some 200 years earlier. [1] [1] Anishinabek Nation is a political organization of 39 First Nations across Ontario.

Millions of other Indigenous objects—some of which are vital to spiritual health and the revival of traditions suppressed by Western authorities—remain in private hands. As an example of a partnership between First Nations, a museum, and a federal government, the pipe’s repatriation offers a roadmap for the return of privately held objects of outstanding cultural patrimony.

THE 1836 TREATY PIPE

To understand the pipe’s importance, one needs to understand Canadian history. In 1830, the ruling British government enforced what was called civilization policy in Canada. The policymakers claimed that First Peoples’ well-being could be best achieved through the adoption of farming, education, and conversion to Christianity: Native people, they thought, would disappear by assimilation into White society.

In 1835, Sir Francis Bond Head was appointed the lieutenant governor of Upper Canada. After an inspection tour, Bond Head decided that the civilization policy was ill-advised. His racist logic was that the Natives were so backward, they were incapable of becoming civilized. He advocated, instead, for isolation: “The greatest Kindness we can perform toward these intelligent, simple-minded People is to remove and fortify them as much as possible from all communication with the Whites.”

Without consulting London, Bond Head decided to act on his ideas in 1836 at the annual distribution of presents at Manitowaning on Manitoulin Island in Lake Huron. He orchestrated a treaty in which the Ottawa Nation and Ojibwe Nation relinquished their claim to Manitoulin so that the 160-kilometer-long island was made the property of all First Nations who chose to live there free of White encroachment. On August 9, the treaty was presented to the 1,500 Ojibwe, Ottawa, Saugeen Anishinabek, and other Native people who had gathered.

For Bond Head, the treaty was sealed by a signed piece of paper. For the assembled First Nations, the deed was done by the sharing of a pipe. Perhaps carved by the celebrated Ojibwe artist Pabahmesad or Awbonwaishkum, the “pipe of peace,” in Bond Head’s words, was “slowly smoked by one chief after another” before being gifted to the lieutenant governor. “A chain of friendship” was forged between those assembled; strings of wampum beads further sanctified the deal.

The British Crown did not approve. Bond Head was removed from office in early 1838, and in 1862, the government negotiated a second treaty with the First Peoples living in Manitoulin. This treaty set up reserves and opened land on the island to White settlement. Many protested—Manitoulin had been promised to them in 1836—and a group refused to sign this second treaty.

Since then, the leadership of Wiikwemkoong, M’Chigeeng, and Sheshegwaning have continued filing grievances and petitions to the Crown for failure to adhere to its earlier promises. Wiikwemkoong’s refusal to sign the 1862 Treaty is why Wiikwemkoong is the only First Nation in Canada recognized as an Unceded Indian Reserve. The territory on the eastern end of the island is home to 8,600 members of the larger Anishinabek Nation.

THE PIPE’S JOURNEY

Before his dismissal, Bond Head returned to England with the pipe and other objects from the 1836 Treaty negotiations. He put them on display in his Croydon home, and after his death the objects passed to his descendants. In 2016, the family decided to sell the objects through Bonhams, the international auction house. Bonhams listed the lot in its 2017 sale of Native American Art.

When an Indigenous scholar from Manitoulin came across the sale, Wiikwemkoong decided to bid on it. It was a substantial outlay for a small community, but Duke Peltier—then the Wiikwemkoong Ogimaa (Chief) and a co-author of this piece—knew that the pipe still had much work to do. The pipe was foundational for Anishinabek, symbolizing both a broken promise by the Crown and a transcendental moment of First Nations unity.

For Ogimaa Peltier and the other Anishinabek who call Manitoulin home, the pipe is also a living entity. The pipe not only embodies their history and traditions, but its spirit needs to be fed and talked to in ceremonies. For too long, the pipe had been away from its people, and now there was a chance that the pipe could return to Manitoulin Island, perhaps to help forge new relationships between Nations in the years to come.

Working with Bonhams, Wiikwemkoong arranged for a direct sale while entering into a conversation with the Canadian federal government. Could it help return the pipe?

The government could, with ROM’s assistance. A partnership was forged that saw the museum purchase the lot in 2020 using a federal grant that stipulated that the museum hold the objects for at least a decade. The solution delayed the transfer to Wiikwemkoong, but it was the quickest way to obtain the necessary funds for the purchase.

In consultation with Ogimaa Peltier, ROM conserved the lot’s pipe and wampum strings, and tested for arsenic and other toxins from prior treatments. The museum also made archival housing that ensured the objects could be stored safely. ROM and Wiikwemkoong then entered into a loan agreement with the Ojibwe Cultural Foundation, an Anishinabek owned and operated museum and cultural center on Manitoulin Island, for the transfer of the Bonham’s lot. The November ceremony celebrated that transfer.

A NEW PATH FOR REPATRIATION

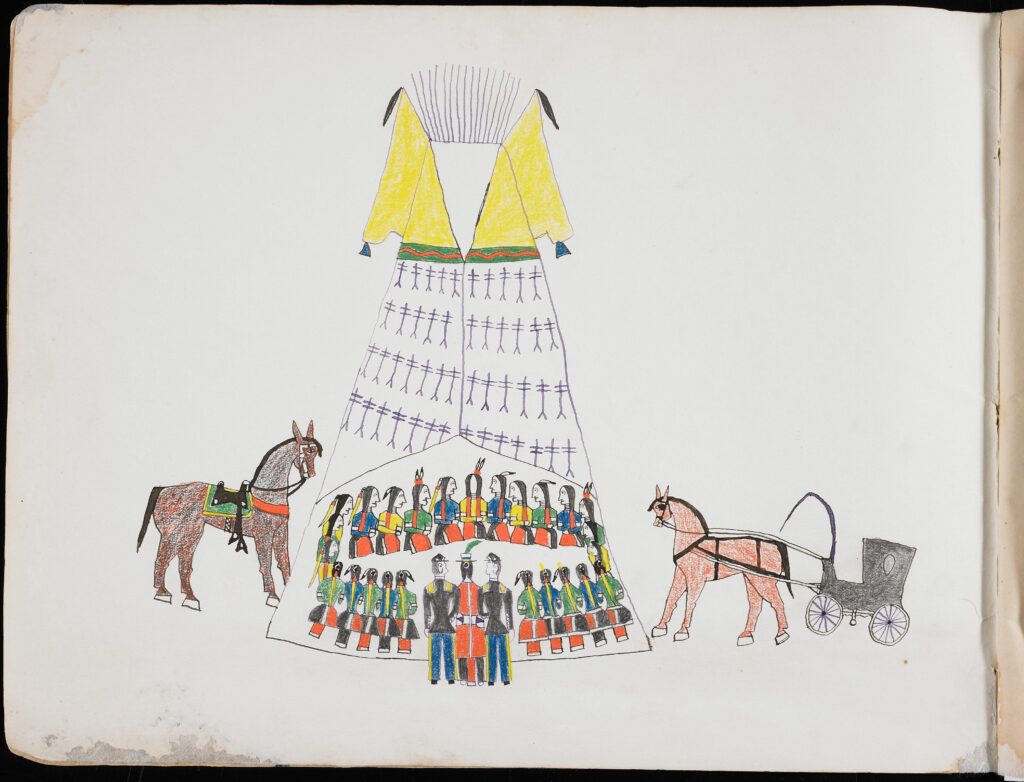

Around the same time that the pipe repatriation ceremony occurred at ROM, there was another sale of Native American art at Bonhams. The collection of Roy H. Robinson sprawled across five catalogue volumes and included important objects like a jacket of Chief Red Cloud (Makhpiya-luta) and four drawing books made by the Southern Tsitsistas and Kiowa men imprisoned at Fort Marion, Florida, in 1875.

These and other objects in the Robinson collection were likely of paramount importance to their respective descendent communities, but few can afford to participate in these auctions. Just one of the Fort Marion drawing books sold for US$353,175. The result is such items often come to light briefly in sales catalogues—then disappear again for decades into private hands.

The successful return of the 1836 Treaty Pipe offers an alternative future for these important objects. It demonstrates that Indigenous groups, museums, and federal governments can work together to purchase, care for, and repatriate cultural patrimony in private collections.

We suggest that Native groups seeking to make an auction purchase could apply for dedicated state or federal funds, with museums serving to temporarily care for objects as preparations are made for their safe return. A jointly organized exhibition, when appropriate, could celebrate a repatriation.

When the 1836 Treaty Pipe is drummed into a ceremony on Manitoulin or passed from one hand to the next, it is helping to undo the damage caused by a racist civilization policy that began in 1830 and ended only in 1996 when the last of Canada’s residential schools closed. By returning home, the spirit embedded within the 1836 Treaty Pipe can continue to remind the Crown of its written promises and realign the First Peoples with the land of their Ancestors.

Other Indigenous objects still in private hands have similar work to do.