What White Power Supporters Hear Trump Saying

Donald Trump’s path to the U.S. presidency in 2016 was paved with warnings about political correctness. Trump railed against it in his campaigning, while also famously referring to Mexicans as “rapists” and calling for a Muslim ban.

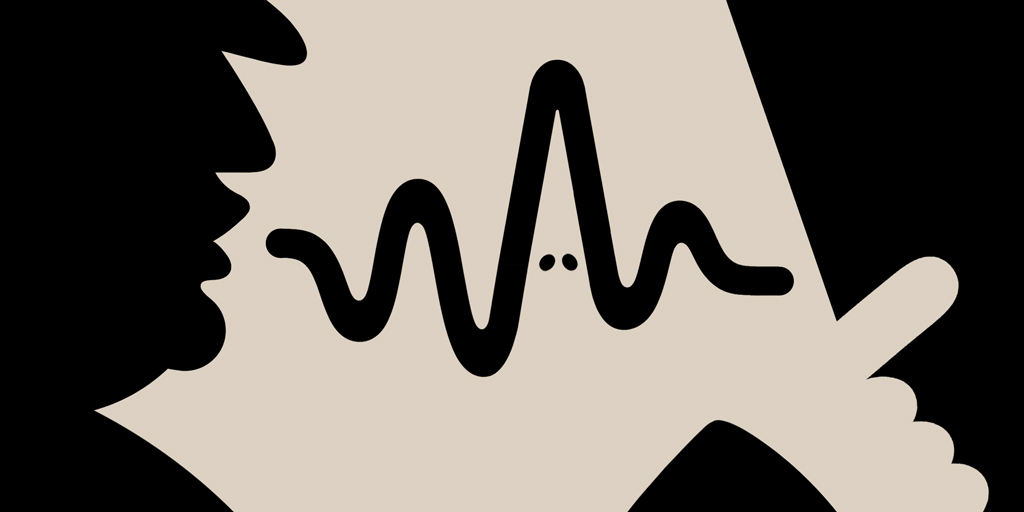

Since then, it has become clear to increasing numbers of Americans that Trump’s attacks on political correctness are a form of racially coded messaging used to stoke the fires of the grievances and fear some White people feel. White power extremists have always heard these racist dog whistles loud and clear.

Now, in the lead-up to the 2020 election, Trump’s White power sympathies are becoming harder and harder for people in the U.S. to ignore. On August 28, in his speech at the Republican National Convention accepting his party’s nomination for the presidency, Trump condemned “cancel culture, speech codes, and crushing conformity.” A few days later, he ordered government offices to stop racial sensitivity training. A memo explaining the change called this kind of training “un-American propaganda.”

Then, in a September 6 tweet, Trump warned that the Department of Education would not continue funding public schools in California that use The New York Times Magazine’s “1619 Project,” which tells the story of the U.S. through the history of slavery and racial injustice, in their history curricula. Days later, it was revealed that Trump likens awareness of White privilege to drinking “the Kool-Aid,” a metaphor for cult-like obedience to dogma. On September 17, he announced the creation of the 1776 Commission, a committee to combat “decades of left-wing indoctrination” about race and oppression that has “defiled the American story.”

For decades, White power extremists have been complaining about the danger political correctness poses to “the White race.” To them, Trump’s remarks are a confirmation of an impending White genocide and race war.

At a time when the Department of Homeland Security has flagged White supremacists as the number one domestic terrorist threat, militias roam city streets, protests against police brutality abound, and the country appears headed toward a contested and perhaps even violent election, Trump’s frequent use of political correctness as a racist dog whistle is adding fuel to the flames.

This must be stopped.

Today most people think of political correctness as a boundary marker of acceptable speech.

For some, political correctness remains a much needed corrective to structural racism and the sorts of identity-based injustices that have returned to public focus during the Trump administration—especially after the killing of African American George Floyd by Minneapolis police in May.

However, more often, the term is used in a negative manner, particularly by those on the right, to warn against Orwellian groupthink and threats to freedom of thought and speech. In the U.S., the term “political correctness” burst into public discussion in the 1990s as part of a conservative critique that claimed identity politics was shutting down debate, especially in universities. A 1990 New York Times essay, “The Rising Hegemony of the Politically Correct,” by the journalist Richard Bernstein, helped spark a controversy that has raged ever since.

Of course, not everyone who attacks political correctness is a White power sympathizer.

But for White power actors, political correctness is explicitly about “race struggle.” This connection can be tracked in the rhetoric and symbolism used by the post–civil rights era White power movement, including by contemporary groups that self-identify as “alt-right.”

I came to understand these connections between political correctness and White power after the 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. Like many across the country, I watched with alarm as extremists marched through the city with torches, chanting “Jews will not replace us!” and “Blood and soil!”

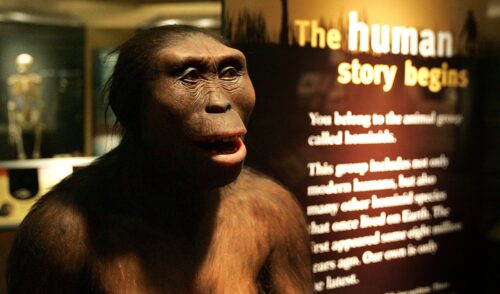

As an anthropologist who has spent years researching genocide, I was familiar with these chants. I recognized the neo-Nazi and White supremacist symbols on display, and I decided to bring my expertise to bear on the problem of White power extremism in the U.S.

I started researching White power ideologies and practices, past and present, and dove into troubling social media ecologies of extremism, ranging from podcasts to message boards like Reddit and 8chan (now 8kun), where extremists spew hate and discuss race war. In 2018, I attended the “Unite the Right 2” rally, the follow-up to Charlottesville held in Washington, D.C., where I observed counterprotester training sessions and took notes on the White power marchers’ racially coded tattoos, statements, and signs. Meanwhile, I taught about White power in my university classes.

Along the way, I came to understand that White power extremists today see political correctness as part of a plot to diminish and even destroy the White race. This research and teaching formed the basis for my forthcoming book, It Can Happen Here: White Power and the Rising Threat of Genocide in the U.S. The title, a nod to writer Sinclair Lewis’ now famous warning about fascism coming to the U.S. in the 1930s, is a cautionary reminder: What happened before could happen again.

An early advocate of these White power ideas in the U.S. was William Pierce, the notorious professor turned White supremacist, who died in 2002. As the founder of a leading neo-Nazi group, the National Alliance, Pierce inveighed against desegregation and other post–civil rights changes that he viewed as the beginning of White genocide.

Pierce’s 1970s dystopian novel, The Turner Diaries, has been particularly influential in White power circles; the FBI has called it the “bible of the racist right.” The novel dramatically depicts Jews orchestrating the destruction of the White race by reorganizing society in a politically correct manner. In response, White rebels launch a race war and commit genocide against people of color across the globe.

Some might dismiss Pierce as fringe. But hundreds of thousands of copies of The Turner Diaries have been sold and many more downloaded from the internet. Similar ideas circulate today in the contemporary White power movement.

White power extremists see political correctness as part of a plot to diminish and even destroy the White race.

Take, for example, A Fair Hearing, an alt-right manifesto published a year after Charlottesville, which includes contributions from leading White power actors such as Richard Spencer. The introduction lays out three key “guideposts” of the movement, all of which are supposedly masked by political correctness: the reality of racial difference (as opposed to the now widely accepted view that race is a social construct), the validity of “the Jewish Question” (a phrase the Nazis used), and the onset of White genocide.

Some contributors discuss these issues in almost apocalyptic terms as a “metapolitical” battle for hearts and minds. They position themselves as opposed to Jewish-led “cultural Marxists,” who they claim control the levers of culture and society, including the media, to brainwash the masses.

For most White power extremists, efforts that embrace multiculturalism and diversity in education and the mass media are nothing but threats to the White race’s survival.

What does all of this have to do with the Trump administration? There is a great deal of evidence that White power understandings of political correctness—as an orchestrated brainwashing that diminishes the White race—circulate at the White House.

In 2017, for instance, National Security Council staffer Richard Higgins produced a memo, “POTUS & Political Warfare,” which is said to have crossed Trump’s desk. The tract is filled with references to cultural Marxism, political correctness, and “deep state” plots. It includes apocalyptic language similar to that used by Trump, including in his Fourth of July Mount Rushmore address and his Republican National Convention acceptance speech.

There are many other White power connections in the Trump administration. Stephen Bannon, the former editor of the alt-right media platform Breitbart News, may have exited the White House, but others remain. For example, emails released last year confirm that Stephen Miller, who orchestrates Trump’s immigration policy and is said to help craft some of Trump’s more inflammatory statements, has strong White power sympathies. The Southern Poverty Law Center recently included Miller in its list of extremists.

Of course, in the end, all you have to do is look at what Trump says. The White power valences of his invocations of political correctness are widespread, frequent, and clear. Like other racist dog whistles Trump uses, including his recent “law and order” messaging, his invocations of political correctness stoke racial division and engender grievance, discord, distrust, and even violence.

The situation is all the more volatile because of White power extremists’ fear of White genocide. Some believe a race war has already begun in the U.S., waged in part through politically correct language.

White power actors are ready to fight. Armed militias are patrolling and facing off in city streets. A loose coalition of anti-government, gun-toting extremists on the far-right, who refer to themselves as “the Boogaloo,” are seeking to spark a civil war. Meanwhile, simulations are predicting a high likelihood of election-related upheaval this fall, potentially on a large scale, unless the results of the race are unquestionable. And, at the first presidential debate on September 29, Trump not only refused to condemn White supremacy but told far-right extremists to “stand back and stand by.”

Trump’s increasingly inflammatory rhetoric, paired with his administration’s erosion of governmental checks and balances and the undermining of the electoral system’s integrity, has created a situation that can easily be set ablaze.

Now, more than ever, people in the U.S. must seek to recognize the White power resonances of Trump’s messaging and related policy initiatives. Doing so is part of an urgent effort to make sure that the small fires of hate and division that Trump is stoking don’t burst into a full-on conflagration.