Can Indigenous Language Comics Save a Mother Tongue?

Tlaloc is a tempestuous deity: provider and withholder. The god of rain, he looms large in the belief system of the Ñäñho people, who reside in the seasonally parched plateau region of Central Mexico. [1] [1] Several Indigenous communities in Mexico refer to themselves collectively as the Ñäñhu peoples (often called Otomies by non-Natives). However, each community’s name and language variant differs by region. In this piece, the designations Ñäñho people and Hñäñho language are used, which are presentations specific to the Mexican state of Querétaro. In the heavens above, Tlaloc lives within a paradise of lush vegetation and endless water in clay pots. If only he’d share.

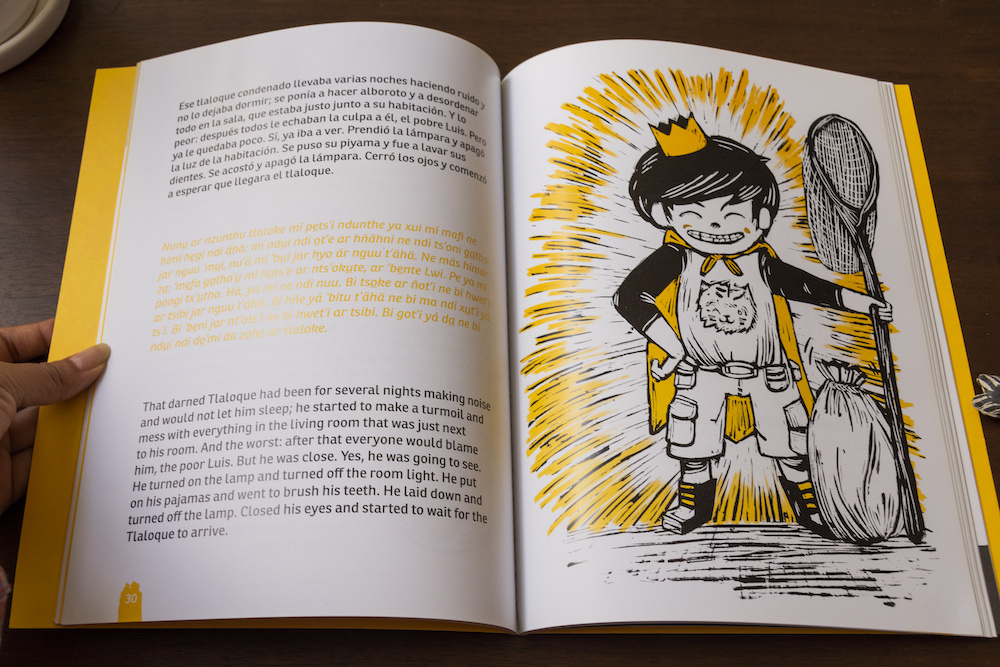

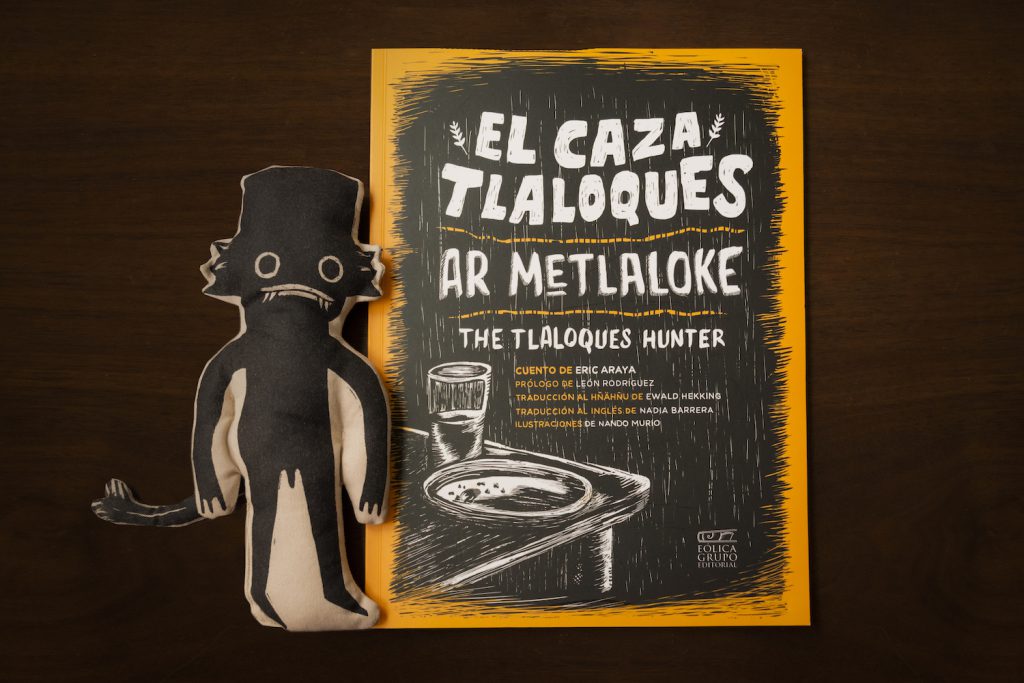

In recent years, a comic book, Ar Metlaloke, (The Tlaloques Hunter), has reimagined Tlaloc’s domain with a twist. The comic weaves in a traditional story from the Mexican state of Querétaro about the spontaneous rainfalls of the mountain Pinal del Zamorano. In the creative adaptation, Tlaloc’s haven includes the Tlaloques, goblin-like helpers who are prone to pranks. They playfully break containers—crack!—and rain pours down unexpectedly onto the arid landscape around Zamorano.

The book is the first of its kind written in Hñäñho, the language of the Ñäñho people, as well as in Spanish and English. It represents a larger, ongoing effort to preserve the people’s culture, which is under threat as speakers decline and cultural bonds erode from centuries of colonial policies.

The language—sometimes called Otomi, from the Spanish name for the community—is imperiled. Today it is one of several regional dialects of a mother tongue with fewer than 300,000 speakers, a figure that’s been dropping for decades.

Limited written Hñäñho has been a challenge for preservation. When linguist Ewald Hekking began researching it 40 years ago, he recalls, “I’d heard there was a local language called Otomi, but I couldn’t find any books.”

Hekking, of the department of anthropology at the Autonomous University of Querétaro, has been working to address that absence ever since. The Dutch-born researcher helped translate the comic, and more recently, he co-authored an anthology of Ñäñho oral traditions and beliefs.

The hope is that telling Ñäñho cultural stories in a contemporary format can help preserve them, and the language, for generations to come.

Hñäñho is one of 68 ancestral tongues still spoken in Mexico, and the seventh largest by number of speakers. But many of these languages are endangered.

About 1 in 5 Mexican citizens self-identify as Indigenous, roughly 26 million people. However, since the 1930s, the percentage of speakers of Indigenous languages has dropped from 16 percent to 6.2 percent, according to the National Institute of Statistics and Geography. At the same time, long-developed knowledge, cultural practices, and intricate details of the land have also been lost.

Many factors have contributed to the steady drop in speakers, including the longstanding policy of “Hispanicization,” or requiring people to use Spanish, which began in the late 18th century under Spain’s colonial rule. The Mexican government later adopted this policy, which intensified after the Mexican Revolution ended in 1920 and the Minister of Public Education José Vasconcelos increased rural education but required lessons to be taught in Spanish.

In the 1980s, when Hekking began to study Hñäñho, schools were meant to offer bilingual instruction. “[But] there were no textbooks in Otomi, and the language was only used to explain the Spanish curriculum,” says anthropologist and freelance consultant Lydia van de Fliert, who has also worked in Ñäñho communities in Querétaro and documented many of their oral traditions.

An emphasis on Spanish continues in schools to this day, despite legislation such as the General Law of Linguistic Rights of Indigenous Peoples passed in 2003, which legally allows citizens to speak their Native tongue in every sphere of public and private life.

Hekking, a sociolinguist by training, first encountered Hñäñho in 1981. He recalls how he’d never heard such melodious rhythms and nasal tones before, despite already speaking six languages plus a bit of Náhuatl and Quechua, two better-known Indigenous tongues from Latin America. Still, he didn’t understand a lick of Hñäñho in that inaugural hearing—and he certainly didn’t know then that he would devote his life to preserving it.

The linguist arrived at a pivotal period. As paved roads were just starting to reach rural communities in the states of Querétaro and neighboring Guanajuato, industrialization was changing Mexico’s economy and Ñäñho people were moving to the cities to seek jobs. Many of these migrants experienced discrimination and, to spare their children similar prejudice, they stopped speaking Hñäñho at home.

Read more from the archives: “Why Are Languages Worth Preserving?”

Hekking began to see a bifurcation between generations. Parents were bilingual or only spoke Hñäñho, and children only spoke Spanish. Oral transmission from adults to children had helped the language survive despite limited writing, but this change troubled him.

Hñäñho is tonal—like many tongues, including Chinese, Punjabi, Zulu, and Navajo—and has a high, a low, and a rising tone. But without written conventions for these sounds, there wasn’t a way to document the language.

Hekking realized that his first task was to describe the orthography, or rules for writing, and its grammar and phonemes, or language sounds. While standards had been developed for Hñäñho by the National Institute of Indigenous Languages, they were based on a Hñäñho variant from another region.

To get started, Hekking needed to examine the particulars of the language in Querétaro. He began working with Severiano Andrés de Jesús, who was born and raised in the predominantly Ñäñho community of Santiago Mexquititlán and was a bilingual teacher with the department of Indigenous education in Querétaro.

In their work, Hekking identified words and phonemes exclusive to Querétaro that would have otherwise been lost. The pair went on to co-author the Gramática of Hñäñho in 1984 and the first bilingual dictionary of the variant spoken in Santiago Mexquititlán in 1989, among other works.

They developed resources to assist in classrooms too. In 2014, they unveiled trilingual courses in Hñäñho, Spanish, and English, which they hope school systems will implement. During the pandemic, Hekking has worked on a virtual course for teaching Hñäñho as well.

Language learners from Ñäñho communities across Mexico, Texas, and California have expressed enthusiasm for the courses—and for new books such as the Tlaloques comic.

Graphic novels and picture books may be especially powerful in connecting younger speakers to their heritage. For instance, the Tlaloques comic has become regular reading in the lessons of Guanajuato-based teacher León Rodríguez García. “When we read the stories in the classrooms,” Hekking notes, “all the students were very interested. They said, ‘We want to read the language of our forebears!’”

“These books are a bridge which connects various generations,” says Jorge Rodríguez, director general of Eólica Grupo Editorial, the Querétaro-based publisher of the comic and the anthology, Ár nthanduximhai ya ñâñho: Honja da thandi, da ts’a ne da ‘bede ar ximhai (Otomi Worldview: A Way of Seeing, Feeling, and Describing the World), that Hekking co-authored.

Comics and other creative projects are increasingly popular ways to convey cultural knowledge, says Jen Shannon, a cultural anthropologist at the University of Colorado, Boulder, and co-host of the SAPIENS podcast. One reason for their power, Shannon notes, is that “when you’re talking about where a perspective is coming from, unlike text, you can’t ignore who’s speaking … they are represented on the page.”

For Indigenous peoples who have lacked a more public platform for telling their own stories, comics can be an effective medium. Shannon co-produces the NAGPRA Comics series, a collaboration with Native communities around the United States to relate their experiences with repatriation.

The visual possibilities of this form also enrich comics. Ar Metlaloke, for example, uses a style resembling the distinctive printmaking of the Taller de Gráfica Popular, a Mexican artists’ collective that produced progressive political publications during the 20th century. By blending Mexican styles with Indigenous cultures that span millennia, Ar Metlaloke celebrates the modern mixed identity of the Mexican people, says Rodríguez, who has two more comic books in the works based on traditional stories from the state of Querétaro.

Even now, as many Ñäñho families have stopped speaking Hñäñho to assimilate into primarily Spanish-speaking communities and others are emigrating to the United States, where they learn English, these books offer a tangible way to carry their language with them and stay connected to their roots. Much like Tlaloc’s coveted heavenly waters, the oral traditions of the Ñäñho have been out of reach for those who no longer speak Hñäñho. But the books, like the raindrops released by impish Tlaloques, could help start a flood of new interest in the people’s stories and language.