How Racism Shapes the U.S. Opioid Epidemic

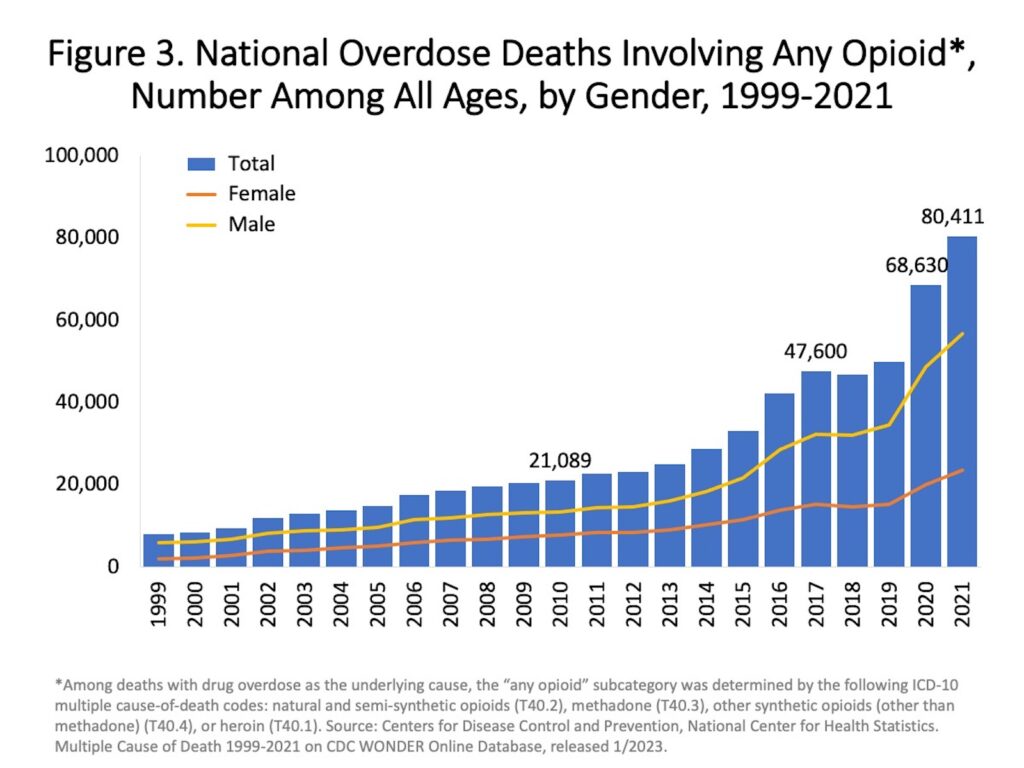

Deaths from opioid overdoses in the U.S. are surging. Overdose fatality rates began rising in the late 1990s, with medical professionals prescribing higher rates of opioids, a class of pain-relieving drugs with addictive qualities. Since 2013, overdose rates have spiked with wider access to powerful synthetic opioids, especially fentanyl.

Media coverage and policy debates on the opioid crisis have predominantly centered the stories of White opioid users, who have accounted for around 80 percent of overdose deaths. But over the past few years, overdose rates among Black Americans have increased precipitously—by 44 percent in 2020 alone. Black Americans are also six to 10 times more likely to be incarcerated for drug-related offenses. As history shows, anti-drug policies have often targeted Black drug users, who are seen as less deserving than White drug users of sympathy, help, and the benefit of the doubt.

To learn more, SAPIENS fellow and anthropologist Marlaina Martin conducted a Zoom interview with Helena Hansen, an anthropologist and addiction psychiatrist who has researched structural racism and drug use and recovery in the U.S. for a decade. The 2023 book Whiteout: How Racial Capitalism Changed the Color of Opioids in America, which Hansen co-authored with public policy sociologist Jules Netherland and historian David Herzberg, is the first book-length critical analysis of how white supremacy and capitalism have influenced the current opioid crisis.

Dr. Hansen holds an M.D. and Ph.D. from Yale University. Her groundbreaking work explores how social structures and belief systems affect people’s well-being and access to health care—for better or worse. Alongside other scholars, Hansen uses the term “racial capitalism” to forefront how powerful companies, governments, other institutions, and individuals have long accumulated wealth and power by exploiting Black, Brown, and Indigenous people, and racist imagery of them. In her research, Hansen stresses how structural racism has played and continues to play into medical and legal practices and policies, leading at times to drastically, even fatally, different outcomes for people.

This interview has been edited for brevity, length, and clarity.

To start out, what are some ideas and misconceptions that you encounter about who uses pain-relieving drugs?

Pain medications that doctors tend to prescribe have changed over time: barbiturates in the 1940s, benzodiazepines like Xanax and Valium in the 1960s and 1970s, and opioids by the 1990s. But across time, we generally see two main ways of interpreting problematic drug usage.

The first, which is often applied to Black and Brown drug users, is incredibly racialized and moralistic. It suggests people who use drugs suffer from a character deficit, which leads to their addiction being normalized, criminalized, and punished.

The other way of understanding drug addiction sees it as a problem that needs clinical treatment and rehabilitation. For over a century, this way has been overwhelmingly associated with affluent, white housewives who went to doctors for medications to treat conditions such as menstrual cramps (from the 1800s with morphine) and anxiety (by the 1960s with Valium). More recently, this subset has grown to include white, blue-collar men injured in industries like mining and construction who, through workers’ compensation, obtain prescription opioids. Many 1990s and early 2000s media headlines about newly patented opioids decried this “new” white face of addiction, often featuring a white woman’s picture or story as an example.

How have medical understandings of addiction as a disease shifted these understandings?

In the 1990s, the growing field of genetics expanded diagnostic understandings of disease. This opened up space for public opinion and medical personnel to meet drug users with sympathy, as they were thought to have a biological predisposition to addiction referred to as chronic relapsing brain disease.

But there are still stark racial divides in how drug users are portrayed in media and treated medically and legally. Across the board, many more white users who run into trouble with opioid addiction are seen as having not a moral problem but a medical one. The same sympathy is not typically extended to Black and Brown users.

Why is it important to understand these racial disparities?

Historically, these racial stereotypes have swayed ideas of which drugs are considered legal, safe, and moral, and which ones are associated with illicit use. And their status can also shift over time.

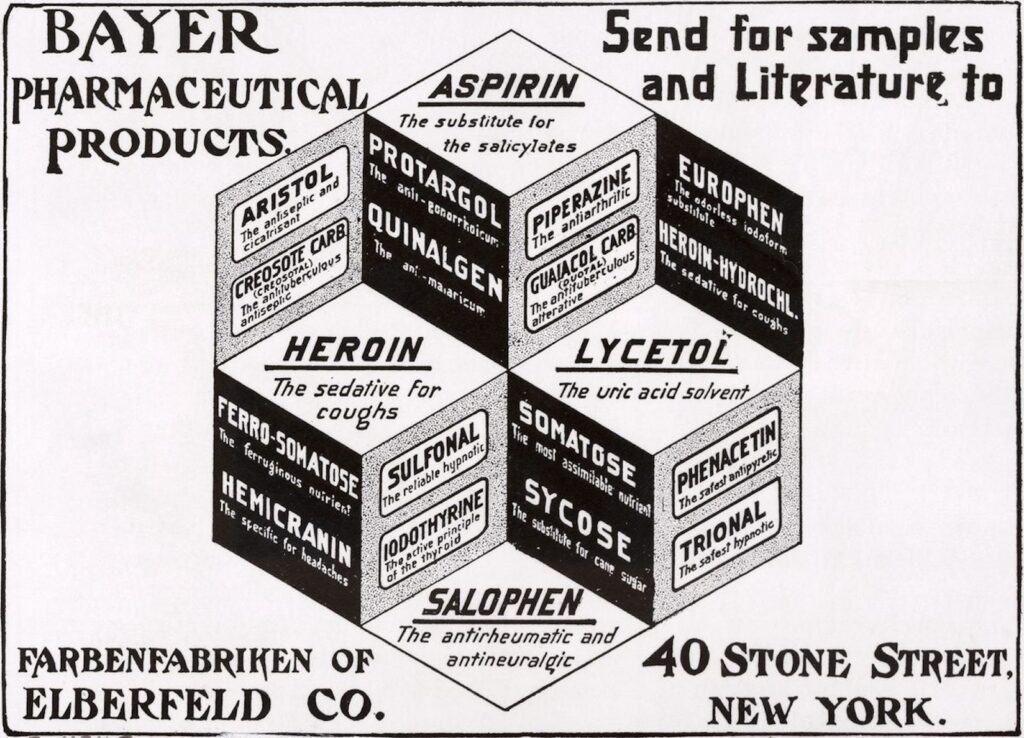

For example, take heroin. It’s illegal today, but heroin was introduced in 1898 by the Bayer Company, manufacturers of buffered aspirin, as a nonaddictive alternative to morphine. (That was incorrect, of course; it’s highly addictive.) Bayer even marketed it to white, Victorian housewives as an over-the-counter cough syrup for children.

However, heroin became harder to access in the early 20th century as international regulations tightened. [1] [1] These regulations include the 1909 International Opium Commission of Shanghai and the 1912 Hague Convention. The U.S. 1914 Harrison Narcotics Act stipulated that doctors not treat people with narcotics addiction, including heroin addiction, with narcotic maintenance. In 1924, medical heroin became illegal.

Interestingly, popular media images of heroin use and users have shifted over time to mirror changing political priorities. It started out as a staple of the white nuclear household, then became a symbol and confirmation of Black pathology during the war on drugs, declared by then-President Richard Nixon in 1971. More contemporary images of heroin addicts feature white, working- and middle-class people stressed out and caught up in what is now largely being framed as a public health crisis.

Basically, what this shows is if you need to make something illegal, you racialize it as nonwhite. If you want to keep something legal, you racialize it as white.

Do racial differences among opioid users show up in any other notable ways?

Assumptions about who can legitimately get and use opioids have also fueled pharmaceutical markets. Generally speaking, U.S. pharmaceutical industries have long centered and pursued white consumers as prospective buyers, albeit implicitly. Not only have white consumers generally had greater access to medical prescriptions and insurance, but doctors have tended to see white consumers as more respectable and responsible than their Black and Brown counterparts. This made drugs advertised to them not only more lucrative but also more likely to get past federal regulators. For example, pharmaceutical promotions of OxyContin in the 1990s centered images of a white, often affluent clientele, framing them as “trustworthy” and at low risk for addiction.

Why do you think you are so invested in the work of understanding how racism impacts the way the U.S. treats drug use?

I grew up in turbulent 1970s Oakland where a lot of political talk was had over the dinner table. I also had two uncles who inspired me as Black Power activists but who also struggled with drug use. Living in my grandparents’ home with my mother, I saw them cycle in and out at different stages of drug use and recovery. I never knew if there would be a police car out front looking for them when I came home from school.

I also grew up with a structural analysis of homelessness and mass incarceration. As a child, after California drastically cut mental health funding, I noticed the streets filling up with people released from the Napa State Hospital, a mental health facility. Without means to survive, many ended up in Bay Area parks. On the way to the bus stop, I would have to step over or run past anyone who seemed “scary.” Two decades after launching on this path into psychiatry and addictions research, I realized that I had been subconsciously channeling my childhood into my critical lens on addiction and mental health.

Later on, as a college graduate in the early ’90s—the peak of the AIDS pandemic—I was inspired by activists seeking and making big changes in policy. Though many were HIV positive, they were out in the streets demonstrating, doing street theater and die-ins, and holding mutual aid house parties to teach one another safer sex and, sometimes, safer drug use. In fact, I worked for the National AIDS Fund as my first “real” job after waitressing. It got me thinking, Maybe I could work from inside medicine but bring a critical perspective.

I know you work both within and outside of formal university settings. Are people having these crucial conversations about destigmatizing opioid addiction and curbing overdose rates? If so, where?

Yes! In fact, I see a lot of these important conversations happening in the harm reduction movement. I have some clinical colleagues who misunderstand harm reduction as an irrational push for everyone to have access to legal heroin, and others who misperceive it as a mechanized public health intervention to hand out syringes for disease prevention. Neither is the case.

Most active harm reduction organizations are social justice organizations. On top of distributing clean syringes, they provide places where people can wash clothes, eat, congregate, join support groups, find employment, and get health care. Many also serve as a base for people who use drugs to begin engaging with politics, advocating for themselves, and learning how their realities are shaped by policies. However, operations like syringe exchange and, more recently, overdose prevention facilities have been illegal in many places, so members of this movement have mostly had to work undercover.

Where should we go from here?

I would like to see the harm reduction movement bridge to other sectors; it makes no sense to have it siloed from addiction medicine. As people committed to reducing drug-related stigma and deaths, rethinking our approaches to study and policy is urgent. Overdose rates are higher than ever and still climbing. They are doing so fastest among Black and Brown people—and, scarily, teenagers.

I’ve also noticed that drug policy has not been a prominent part of prison abolition discourse even though the criminalization of drugs has obviously been a major driver of mass incarceration. This needs to change.

I think those of us working within medical and racial justice organizations must join forces with one another. We must also be in conversation with those harm reduction organizations whose members have personal experiences that could greatly benefit pushes for drug policy reform. We cannot afford to dodge the issue or work in siloes any longer.