Kenyan Mothers Take on Police Violence

Kenyan Mothers Take on Police Violence

I first met Sarah Wangari three weeks after her son Alex had been killed meters away from her house in the urban settlement of Mathare in Nairobi, Kenya. According to Sarah, Alex is one of the numerous victims of a notorious police officer named Ahmed Rashid, who for close to a decade has terrorized and killed residents within the southeastern part of the city known as the Eastlands area. As she recounted, Alex’s only crime was to come back “late” from work—breaking the unofficial curfew that the police use to patrol those who live in the city’s poor neighborhoods.

Rashid has been caught executing young men in broad daylight, and he was even featured in a contested BBC documentary, which critics felt was problematic for its sympathetic portrayal of his actions. To my knowledge, he has never been discharged from the police force nor prosecuted for his human rights violations.

Instead, official representatives claim that such violence is justified due to crime levels and terrorist activity. Former police spokesman Charles Owino has commended Rashid for “combating crime in the city.” I’ve observed that these kinds of defenses of police violence have been tacitly supported by a majority of middle- and upper-class residents in Nairobi who have remained silent in the face of these killings of the poor.

The community of Mathare, where I have worked as a community organizer and anthropologist for over a decade, is populated by close to 207,000 people who live in a former quarry only 3 square kilometers in size. Since the British colonial era, which ended in 1963, the densely populated shack dwellings, and the people living in them, have been stigmatized and seen as unwanted in a Nairobi reaching toward “development” and “modernity.”

I describe this area as an “outlaw space”: a place where people are both criminalized and forced outside of the law, creating a situation where they are deprived of social and legal recourse to make basic claims to life.

In this context, Alex’s murder is not unique. At the Mathare Social Justice Centre (MSJC), where I volunteer as the participatory action research coordinator, we launched a report in 2017 that detailed over 800 killings by Kenyan police between 2013 and 2015. Every year, organizations like the Independent Medico Legal Unit and Missing Voices document hundreds more police killings and disappearances of predominantly young, poor men in Kenya.

As both a researcher and community organizer, I have had the opportunity to think more deeply about how the state governs these populations and neighborhoods with the help of people like Sarah—second- or third-generation dwellers in these poor urban spaces. I’ve found these areas are controlled through a sinister combination of neglect and force. But community members survive, and through a medley of small but powerful actions, they stake their claims to a city that does not want to affirm their existence.

After close to three years of mourning, a period when she struggled with alcoholism and could not bear to go inside the small, corrugated iron sheet shack where Alex had lived, Sarah joined an alliance called the Mothers of Victims and Survivors Network. Becoming part of this association changed her life.

Started in 2017, the network brings together close to 70 mothers, widows, and other family members—including sisters, fathers, and brothers—of people who have been killed by the police or who have endured police brutality. The larger mandate of the network is to offer solidarity and emotional and psychological support to members, document human rights violations, and come together to demand legal recourse and seek justice for their cases. The members range in age from 19 to 75 and come from diverse ethnic and religious backgrounds. The organization has since grown to include other settlements in Nairobi.

I describe Mathare as an “outlaw space”: a place where people are both criminalized and forced outside of the law.

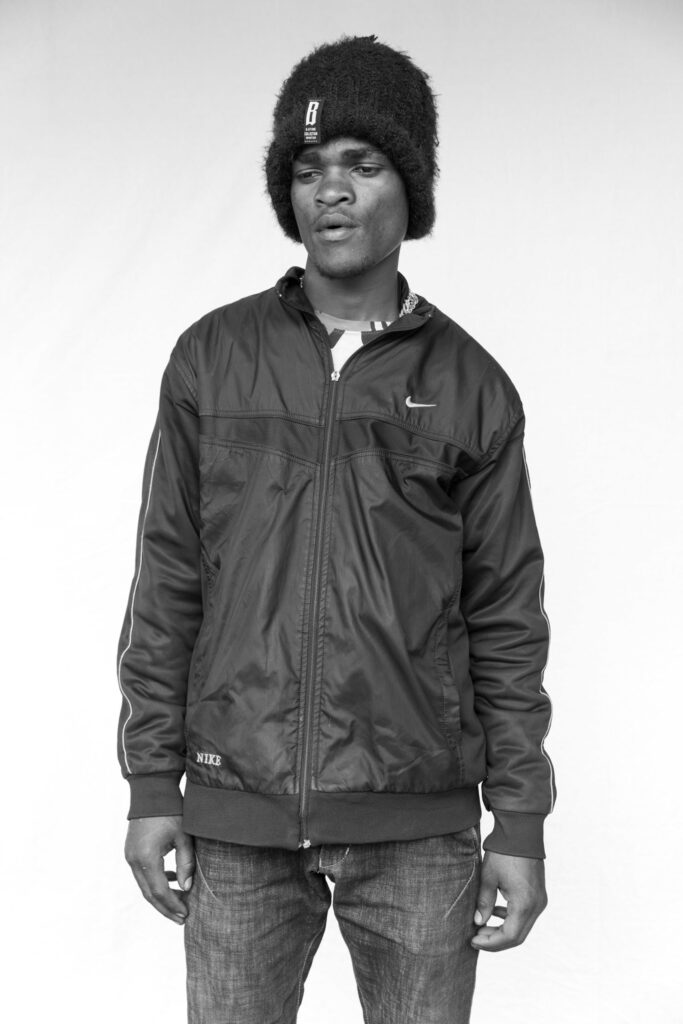

Recently, Sarah played a role in documenting network members’ stories in a participatory report called “From Victims to Community Defenders.” With support from MSJC and a grant from the Norwegian Human Rights Fund, the mothers worked to compile their experiences of the deaths of their kin. The resulting report sheds light on the impact of state terror and structural neglect through statistics on police killings and harrowing stories alongside photos. The slideshow accompanying this essay includes a selection of the stories and stark, black-and-white portraits included in the report, which were taken by photojournalist Ed Ram.

The report also highlights the historic racial segregation constitutive of the planning of Nairobi that continues to create different experiences of life in the city, now also shaped by class. As I explore in my ongoing research, Nairobi’s urban spatial management reproduces colonial divisions, where poor residents are treated like “Natives” at the bottom of a strict class and race hierarchy.

As a result, communities like Mathare have for decades survived without basic infrastructure: no piped water network or electricity, inadequate housing, and minimal sanitation facilities. Alex’s job was fetching and selling water to Mathare residents, who experience what scholars elsewhere have called “systematic dehydration” due to what seems to be the intentional absence of water infrastructure. The police killing of this young man, who was coming home late because he was providing water to residents who have never had piped water, is a grave manifestation of the structural violence inherent to this colonial model of urban planning.

In Nairobi, where the deaths of people like Alex have been normalized, Sarah and the other members of the network are attempting to denaturalize the state violence that targets their communities. As part of this work, the network has also curated a photo exhibition that builds on their recently released report. Currently on view, the exhibition at the Circle Art Gallery—located in the prosperous Lavington area of Nairobi—showcases Ram’s photos of family members who have lost kin to police violence.

This exhibition is a rare event in a wealthier area where residents often stay silent about the extent of extrajudicial executions. The network hopes it will rally greater awareness, especially among Kenya’s habitually apathetic middle and upper classes, of the police violence that has destroyed so many lives and that continues to terrorize poor urban dwellers. These efforts are akin to the actions of defiant groups of mothers in Argentina and Brazil who are at the forefront of demanding both justice and the cessation of state violence against their communities.

Though initially immobilized by grief after her son’s death, Sarah has become a critical member of the network; she now channels her struggle into determined activism. Though she must walk past the spot where Alex was killed to engage in this social justice work, she perseveres. And through this dedicated labor, she, like other activists in the network, has gone from being a victim to being a community defender.