An Archaeology of Marijuana

In June, the recreational and medical marijuana industry in my home state of Colorado reached US$199 million in monthly sales, a new record.

The growth of this industry has been eight years in the making. In 2012, with the passage of Amendment 64, Colorado became, along with Washington State, one of the first states in the U.S. where consenting adults could legally purchase and consume cannabis for recreational purposes.

Since then, the tourism landscape in Colorado has changed tremendously. The legalization of recreational marijuana has contributed to six of eight consecutive years of record-setting growth in the tourism industry. In June 2019, the Colorado Department of Revenue announced the total revenue line for marijuana reached US$1 billion since sales started in 2014. These monies provided the state with hundreds of millions of dollars in new tax revenue to pay for education, transportation, environmental protection, and other initiatives.

Still, despite the obvious economic benefits, many in the U.S. disapprove of the legalization of marijuana. Some friends of mine simply complain about the smell of pot. Others worry about teenage marijuana use, the potential effects of secondhand smoke on children, or about people driving while stoned.

I haven’t smoked in years, and I haven’t (yet) tried edibles. But I am thrilled that the U.S. has begun making the long journey away from the unnecessary criminalization of a mild recreational drug.

I voted yes on Amendment 64 because of the double standard in the U.S. with respect to alcohol, which studies show is far more dangerous than marijuana. I also voted yes because I objected to the systemic racism of a judicial system that disproportionately punishes people of color for drug-related offenses.

My perspective as an archaeologist also had something to do with it. As someone who pays a lot of attention to what humans did in the past, I know that not everything modern is “normal” when viewed through the long lens of human experience. The modern fear of marijuana is one of those preoccupations that seems especially strange in light of the fact that researchers estimate humans have been using cannabis for at least 10,000 years.

What do scholars say about this long history of cannabis use by humans? How did cannabis go from being a plant highly valued in many parts of the world to a vilified drug?

A good place to start is with paleoethnobotanists, who study the relationships between people and plants as recorded in the archaeological record. Besides being a fun word to say, paleoethnobotanists have helped uncover the earliest agriculture on the planet, explore genetic modifications in domesticated plants, and unveil thousands of plant species used by human societies in the past that may have been forgotten.

In 2008, archaeologists and a team of other researchers working in the Yanghai Tombs near Turpan, in the Xinjiang-Uighur Autonomous Region in northern China, discovered one of the oldest documented pieces of botanical evidence of humans using cannabis for its pharmacological properties. Paleoethnobotanists identified the cache of nearly two pounds of 2,700-year-old cannabis found in the burial pit of a 45-year-old man who excavators concluded was a shaman from the ancient Indo-European Gūshī culture.

Based on a range of chemical and other analyses, the research team found that members of that society “cultivated cannabis for pharmaceutical, psychoactive, or divinatory practices.” However, they could not determine how the cannabis might have been consumed or administered.

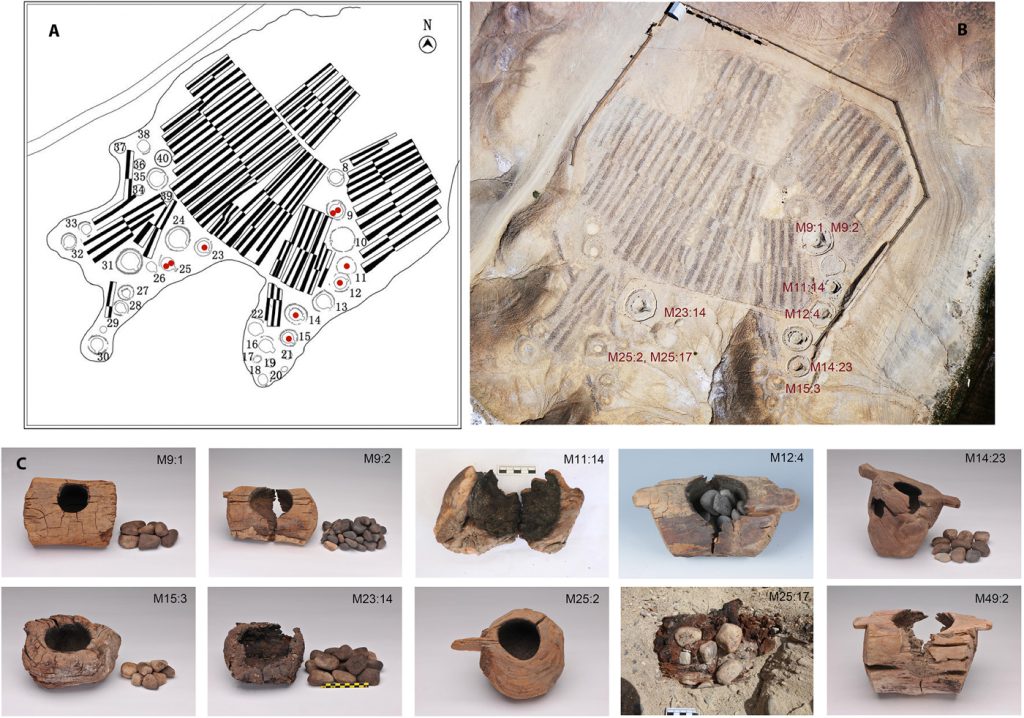

In 2019, archaeologists working in western China announced another major discovery: the oldest known evidence of cannabis smoking by humans. They uncovered 2,500-year-old braziers, vessels designed to create large quantities of smoke, that contained residues of a highly potent form of cannabis—suggesting that the plant was burned and inhaled.

The site, the Jirzankal Cemetery, is located at an elevation of about 10,000 feet, where cannabis is known to grow wild. Some of these varieties might have contained high quantities of the psychoactive compound THC. Paleoethnobotanists continue to study the residues found at Jirzankal for insights into how people may have manipulated cannabis to yield plants with desirable qualities, such as higher THC levels or stronger hemp strands.

Based on these findings and many others, paleoethnobotanists show that people were using cannabis as far back as 10,000 years ago. Trade routes linking Europe and East Asia may have increased the use of the herb around 5,000 years ago.

Although archaeologists have only begun to understand the role that cannabis may have played in these societies, we know it was an important one.

Fast forward to the 19th century. By then, cannabis had made its way to the U.S.

In 1850, cannabis was added to the United States Pharmacopeia, a standard-setting publication for prescription and over-the-counter medicines. For more than nine decades, the pharmacopeia listed cannabis as an approved treatment for afflictions ranging from neuralgia to cholera.

By the early 20th century, pharmaceutical companies—including Parke Davis (now owned by Pfizer), Squibb of Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Eli Lilly—were selling cannabis extract for medicinal purposes. For nearly a century, cannabis use was legal and even encouraged by many in the medical field in the U.S.

Then, in 1936, the movie Reefer Madness was released. The film depicts a high school principal warning parents at a middle school Parent Teacher Association meeting about the supposed dangers of marijuana use. Now a cult classic, Reefer Madness demonized cannabis by arguing, in no uncertain terms, that its use led to violence, addiction, wanton sexuality, and other social ills.

Reefer Madness added fuel to ongoing efforts by local, state, and federal governments to put in place harsher regulations of substances. The film came on the heels of the failed effort to prohibit alcohol use in the U.S., an effort codified in the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1919 and repealed by the 21st Amendment in 1933.

Once Prohibition failed, authorities turned to cannabis, which at that time was associated with communities of color, particularly Mexican immigrants, Mexican Americans, and African Americans.

Although archaeologists have only begun to understand the role that cannabis may have played in the past, we know it was an important one.

In 1937, the U.S. government passed the Marihuana Tax Act. Though this law did not criminalize cannabis outright, it subjected the herb to a high sales tax and put in place other penalties intended to curtail its usage. In 1942, cannabis was removed from the U.S. Pharmacopeia.

In 1972, after the start of the Nixon administration’s epically futile war on drugs, cannabis was listed as a Schedule I drug, along with LSD, ecstasy, cocaine, heroin, and other far more dangerous drugs. After thousands of years, the full transition from cannabis as a recreational and medicinal product to an illegal drug in the U.S. was complete.

According to a 2016 report compiled by the United Nations, this heavy enforcement approach to drug policy created a huge illegal market for illicit drugs. It arguably led to more overdoses and addiction than controlled access to drugs. It led to disproportionate incarceration rates in communities of color, and may have resulted in higher rates of communicable diseases such as HIV and hepatitis C. In short, the war on drugs was a failure.

Already, the tides are turning. Recreational marijuana is now legal in 11 states across the U.S.; my original home state of Illinois joined the fun on January 1 of this year. Several other states are set to vote on marijuana legalization on election day, November 3.

The irony is that now, with large pharmaceutical companies reentering cannabis markets, those corporations will be making money off the very communities of color that have been disproportionately targeted and incarcerated by anti-marijuana policies. Some lawmakers are calling for the legalization of marijuana at the federal level and policy changes to rectify this injustice and level the playing field, such as the Marijuana Opportunity Reinvestment and Expungement (MORE) Act, a bill which is set to be voted on by the U.S. House of Representatives this fall.

Again, Colorado is leading the way: Governor Jared Polis announced on October 1 that he will issue a blanket pardon of 2,732 low-level state-court convictions for possession of up to an ounce of marijuana prior to 2012. It’s a step in the right direction.

With the increase in legalization, there have, of course, been issues. As I’ve seen in the eight years since Amendment 64 passed, there have indeed been problems resulting from its legalization in Colorado, including increased pediatric exposure to the drug over the last several years.

But that brings me right back to the double standard in the U.S. with respect to alcohol and cannabis consumption. I was a bartender for many years and drank alcohol for many more years before quitting after my 40th birthday party. Based on personal experience, I know that cannabis is less dangerous than alcohol when consumed by consenting adults. Full stop.

But you don’t have to take my word for it. Cannabis has at least 10,000 years of study behind it.

If I were a betting man, I’d say that recreational cannabis will be legal in most states across the U.S. and at the federal level by 2030. It’s one of the few new sources of tax revenue, and the war on drugs has been a colossal, expensive, systematically oppressive fiasco.

Let’s let the market do its work, and let’s tax the heck out of this long-loved herb.

Correction: October 20, 2020

The Marihuana Tax Act of 1937 did not place the regulation of cannabis under the Drug Enforcement Agency. The agency was established in 1973. In addition, Attorney General John Mitchell, not the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, listed cannabis as a Schedule I drug in 1972.