Is Love a Biological Reality?

Helen Fisher knows more about love than most. As a biological anthropologist who studies the topic, she has been a chief scientific adviser to the internet dating site Match.com since 2005 and given three TED talks on love.

Fisher and her colleagues have put more than 100 people into a brain scanner (using fMRI) to study love’s sway, and more than 15 million people have taken her personality questionnaire. She has studied a worldwide trend that she calls “slow love,” in which people spend more time in the initial stages of courtship before committing to a relationship. As she shared with the SAPIENS podcast, she believes the pandemic may further stretch this phenomenon—thus improving the stability of future marriages.

At 75 years of age, she says she has finally discovered the true power of love: She was married in a small ceremony in July 2020. SAPIENS spoke with her about the biological basis for love and what those insights mean for human societies.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and brevity.

How would you, as a biological anthropologist, define love?

Romantic love is a basic brain system, like fear and anger or disgust. We humans have evolved three distinct brain systems for mating and reproduction: the sex drive, romantic love, and feelings of deep attachment. People make the mistake of thinking that these are phases. They’re not phases, they’re brain systems, and they can operate in any combination and order.

I went through the last 40 years of psychological material looking for how academics define love, and here are some of the basic traits. Someone you love takes on “special meaning.” You focus your attention on them. You have high energy when you’re in love: You can walk all night and talk till dawn. You have mood swings and real bodily reactions: weak knees and dry mouth, butterflies in the stomach. You feel emotional dependency and separation anxiety.

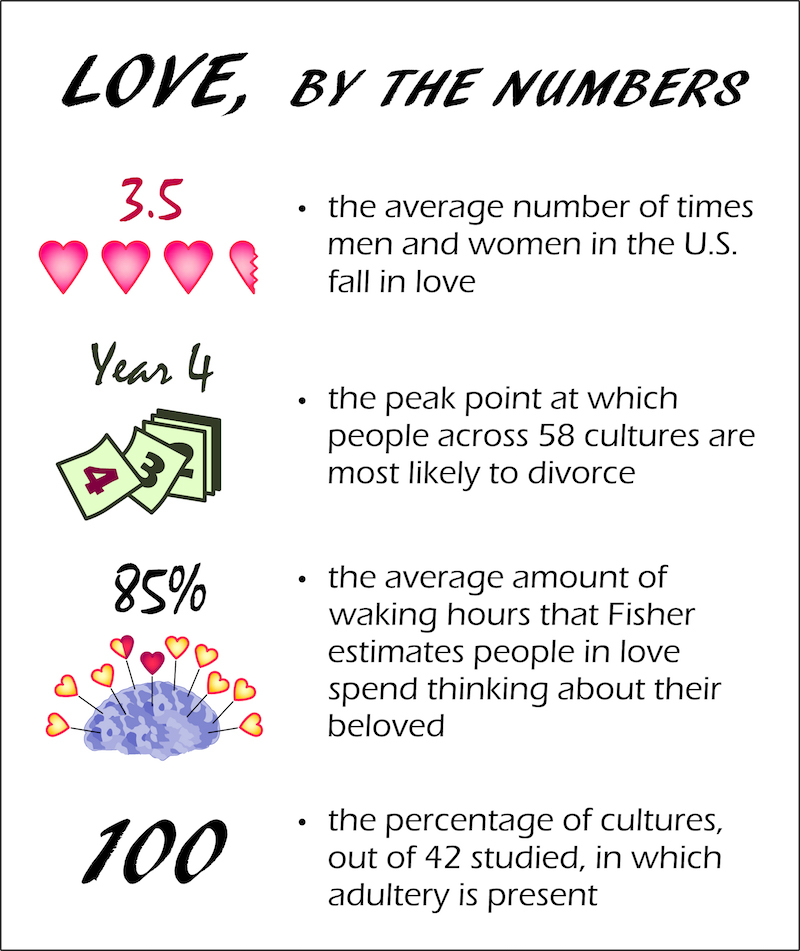

People say they think about their loved one all day and night—it’s called “intrusive thinking.” I estimate the people I studied, on average, thought about their beloved about 85 percent of the time.

You have put people feeling romantic love into an fMRI brain scanner. What did you see?

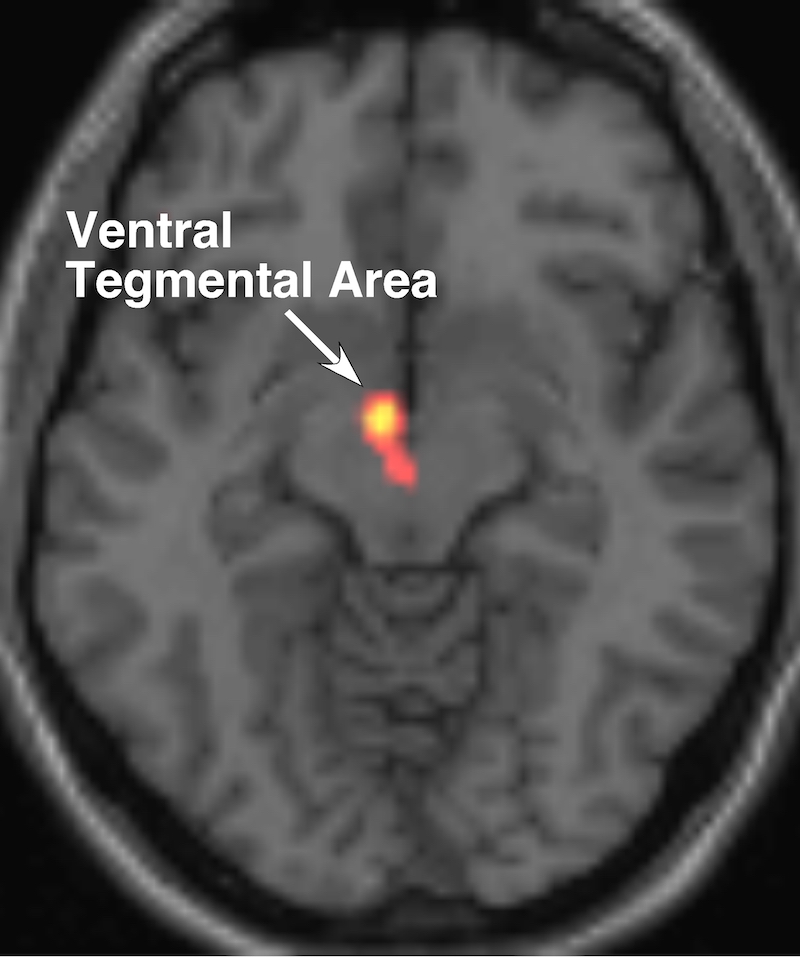

Romantic love comes with a lot of different emotions. But in the brain scanner, everyone who is madly in love has common activity way in the base of the brain: in the ventral tegmental area (VTA). This brain region pops up the dopamine—a chemical messenger in the brain that gives you energy, focus, motivation, and craving.

Does that tell you something about why romantic love evolved?

The VTA lies right next to the hypothalamus and pituitary, primary brain regions that orchestrate thirst and hunger. Thirst and hunger keep you alive today. Romantic love drives you to fall in love, form a partnership, and send your DNA into tomorrow. Romantic love is a survival mechanism.

Can brain chemistry help us identify a love match?

I went through decades of the medical and academic literature for two years looking for any personality trait linked with any biological system. I looked at everything from the effects of drugs of abuse to drugs for diseases or those taken by people changing their gender. If you take estrogen replacement, for example, your linguistic skills increase.

I found four systems connected to chemical messengers in the brain—dopamine, serotonin, testosterone, and estrogen—each associated with a constellation of personality traits. That’s the basis for the questionnaire I created for Match.com.

But I needed to see: Have I got this right? So, I put people into the fMRI machine to do brain scanning. People who scored high on the serotonin scale on my questionnaire, for example, showed more activity in a tiny area of the brain linked with social norm conformity. And those who scored high on my estrogen scale showed more activity in a part of the brain linked with the mirror neurons, associated with empathy.

Then, in a sample of 40,000 people, I watched who was immediately drawn to whom—it’s the purest way to understand nature’s role in mate choice (that work is forthcoming in the Handbook of Human Mating). What I ended up finding is that people who are very expressive of the traits in the dopamine system on my questionnaire chose to go out with people also high on my dopamine scale. (See here for more matches.)

How universal are your findings?

The president of Match.com came to me and said, “Helen, will your questionnaire work in other countries?”

I said to him, “If it doesn’t, I have failed. I’m not studying the American brain; I’m studying the human brain.”

My colleagues put people into an fMRI machine in China, too, and found exactly the same activity related to being in love. Around the world, people pine for love, live for love, kill for love, and die for love. It’s one of the most powerful and basic brain systems humanity has evolved.

But just because I study the biological aspect of behavior, I’m not denying the impact of culture. These two major forces always go together. Who you love, where you love, how you express your love all have a huge cultural component. But the actual feeling of romantic love, that’s biological.

NJ: Would you say there are just a handful of people out there who would make someone happy? Or dozens? Thousands? Millions?

HF: I would never put a number on it, but it’s certainly more than one. I’ve got unpublished data on more than 50,000 people from the U.S. census, and the average number of times that American men and women fall in love is 3.5.

Are humans designed to be monogamous—or not?

Monogamy means forming a partnership, a pair bond. It means “one spouse.” To scientists, it does not mean fidelity to that spouse. Over 90 percent of bird species form a pair bond, for example, because someone has to sit on the eggs. But they also cheat.

We humans have evolved a dual reproductive strategy: a tremendous drive to fall in love, form a partnership, and rear our children as a team; and also, a drive to philander. I looked at adultery in 42 cultures and found it in every one, even in societies where you can get your head chopped off. For a man, adding a lover can mean doubling the amount of DNA he sends into tomorrow. A woman can get a lot of extra resources, such as meat and protection, or get a lover to step in if her partner gets eaten by a lion. I don’t believe that men are, by nature, more adulterous than women.

Given our desire for a partner and our tendency to cheat, how long do marriages last?

I looked at the demographics from the United Nations from 1947–2011 and across 80 cultures. People tend to divorce around the fourth year of marriage. I thought it would be seven years—that’s enough time to raise two children through infancy. So, why did we evolve to have a four-year divorce peak? It began to occur to me: If it’s an unhappy and unstable partnership, and partners leave each other, they both have the opportunity to have children with someone else, creating more genetic variety in their lineage.

Do people with long-term, happy partnerships share any traits?

Yes, in the brain. In our lab, older people would come in, people in their 50s and 60s, and say, “I’m still in love with her,” “I’m still in love with him.” So, we put them in the brain scanner. We found activity in regions associated with the VTA, which produces dopamine, and a brain region associated with attachment. These people really are still showing the biological signs of romantic love, decades after getting together.

People in long-term, very happy partnerships also showed activity in three brain regions. Those were associated with empathy, the ability to control their own stress and emotions, and something we call “positive illusion,” the ability to overlook what you don’t like about a person and focus on what you do. As former Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s mother-in-law said to her: “It helps to sometimes be a little deaf.”

If anyone in the world can make a “love potion,” it’s you. Is such a thing possible?

I don’t think so. There are very good academics who do think that it’s completely possible. And there are drugs that can possibly amp up the dopamine system: All you gotta do is take an amphetamine. But you don’t necessarily fall in love; you might just want to clean out your closet. More important: These drugs wear off.

How has marriage changed over the generations?

Anthropologists will tell you in a hunter-gatherer society, the double-income family is the rule. Women commute to work to gather fruits and vegetables; they come home with over 50 percent of the evening meal. Women are generally seen as economically, sexually, and socially powerful.

Then we settled on the farm, and women’s roles declined. What women really had to do was have a lot of babies to help out on the land and in the barn. In farming cultures, you really see the rise of a whole set of new beliefs, including virginity at marriage, a woman’s place is in the home, the man’s the head of the household, and till death do us part. It’s hard to divide up a cow or take half a wheat field if you divorce, so marriage became regularly lifelong.

Today all those agrarian beliefs are vanishing before our eyes. We are moving forward to the past, onward to the kind of relationships we had a million years ago. This is much more compatible with our ancient human brain.

Has your research on love collided with your own romantic relationships?

I met my husband six years ago at a private ranch. He offered to drive me to the airport; it was a 2 1/2-hour drive. He was going through a bad divorce and was a single father. He said, “I’m never going out with a woman again.”

So, for the first year, we would go to the opera every six weeks or meet in a group of mutual friends. After about a year, he wanted to be “friends with benefits”; he didn’t want a long-term thing with commitments.

Here’s where my understanding of anthropology came in. I said: “You know, I study love. When you have sex with somebody, you can drive up the dopamine system and fall in love. Casual sex isn’t casual.” I asked if he was willing to take the chance of falling in love.

He said, “Yes.”