Repatriation Has Transformed, Not Ended, Research

Disclaimer: This piece includes discussion of Ancestors, ancestral remains, and scientific research involving Ancestors.

In 1996, the discovery of a skull on the banks of the Columbia River in Kennewick, Washington, sparked an intense controversy and a yearslong court case.

The remains belonged to an individual—dubbed “Kennewick Man” or “the Ancient One”—who lived between 8,340 and 9,200 years ago. Within months, the Army Corps of Engineers, which had jurisdiction over the remains, announced that they planned to return the bones to five Native American tribes who claimed the Ancient One as their Ancestor. In response, a team of eight scientists launched a lawsuit claiming their right to study the remains.

The ensuing conflict climaxed in 2015, when a DNA study performed in collaboration with the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation confirmed the tribes’ position by providing a strong link to Native American groups. The U.S. Congress acknowledged years of political advocacy by the tribes and soon passed a law for the Ancient One’s transfer to the Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation. The Ancient One was reburied in 2017, more than 20 years after his initial discovery.

The trial and the Ancient One became famous. It’s easy to see why. For the media, it was a good story: a lengthy and high-profile legal battle with many actors. At the time, few individuals dating to that period had been found, so the Ancient One was potentially very important for understanding the peopling of the Americas. The debates emphasized the conflicting interests of science, politics, and religion.

But the extensive notoriety afforded to this case, and others like it, negatively impacted both academic and public impressions of repatriation—the return of ancestral remains and other cultural patrimony to descendant groups from institutions like museums and universities. Such controversial cases often overshadow more collaborative repatriation work and promote the idea that repatriation is always incompatible with scientific research.

This myth persists today. It is often why institutions continue to resist repatriation. For example, the 2020 book Repatriation and Erasing the Past argues that repatriation has harmed science and threatens to end certain types of archaeological research. It garnered significant backlash online, including a petition for the book’s retraction.

It is true that not all descendant communities are interested in pursuing archaeological and anthropological research. For many, their Ancestors’ very presence in institutional collections is evidence of traumatic histories and colonial violence. Repatriation, even when mandated by legislation or policy, also faces continued resistance and, for some, remains out of reach.

Our aim is not to convince descendants that research is important. Instead, as settler anthropologists, we are pushing back against the institutional narratives that see repatriation as incompatible with research. We are countering the notions that collaborative work is “non-scientific,” “biased,” or even an imposition on academic freedom.

Read more, from the archives: “Confronting Cultural Imperialism in Native American Archaeology”

Frankly, these arguments too often dismiss the important transformations that repatriation has brought to research practices and the many successful collaborative projects that have developed. Indigenous scientists and community-based researchers are leading the way. Our recent edited volume, Working With and For Ancestors, shows how research of all kinds—from oral history work to DNA analysis—has featured prominently in many repatriation cases where researchers sought to work with and for descendant communities.

Research involving Ancestors can certainly take place alongside repatriation. But for that to work, respectful relationships between institutions and descendant communities must be developed and maintained, the wishes of community partners need to be prioritized, and community control over the disposition of their Ancestors must be respected. This may not always be easy, but it is always worthwhile.

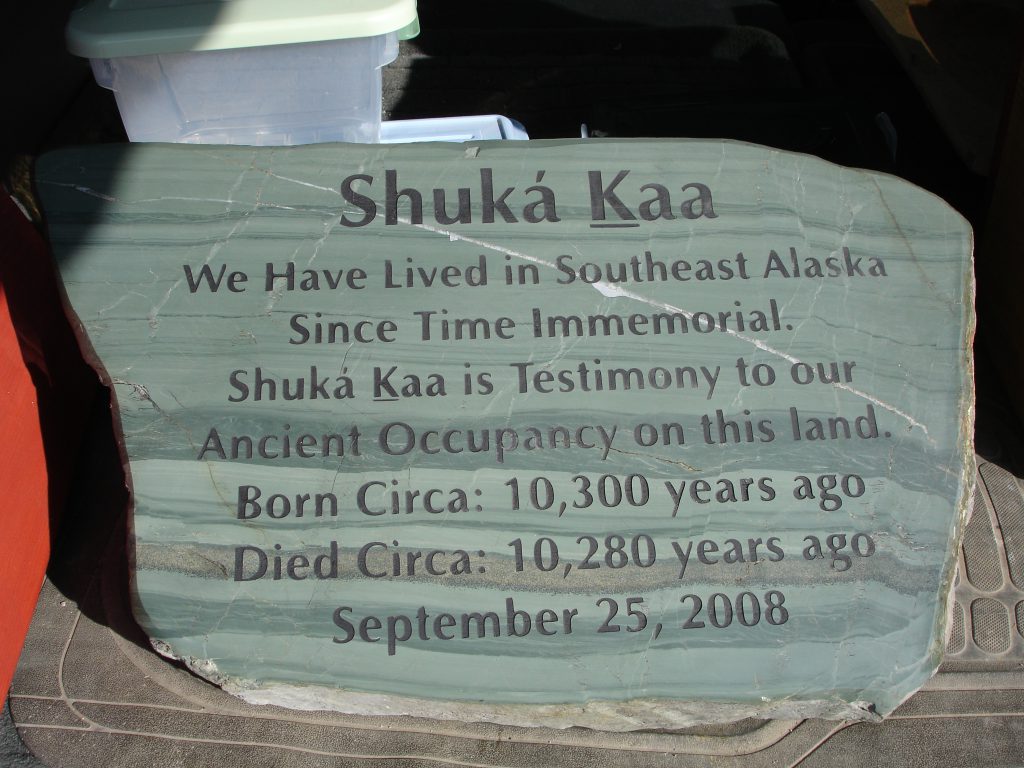

The same year the Ancient One was found in Washington, an Ancestor known as Shuká Káa (“The Man Ahead of Us”) was found on Prince of Wales Island in Alaska. Shuká Káa was another important individual for our understanding of the past; however, his story would follow a very different path.

Within 24 hours, archaeologists had contacted local tribal governments to inform them of the discovery and to request permission to study their Ancestor. After consultation and negotiation, the tribal governments agreed to the scientific investigation of Shuká Káa, including DNA analysis (which involves removing a portion of a tooth or bone), so long as the community continued to be closely involved in the research.

Initial studies did not reveal a clear link between Shuká Káa and DNA samples taken from 200 Tlingit community members. Shuká Káa was repatriated and reburied close to where he was found in 2008. However, with the community’s consent, a small sample of dental tissue was retained for later re-analysis. In 2017, a new study found that Shuká Káa was likely a distant Ancestor of contemporary Indigenous groups in the Pacific Northwest, including the Tlingit.

What was different in the case of Shuká Káa compared to the lengthy controversy surrounding the Ancient One?

Comparing them shows that two essential components of mutually beneficial research partnerships were present in the case of Shuká Káa: respect for the wishes of the descendant community and a collaborative approach to research. Archaeologists also had a preexisting working relationship with the local tribal governments, and repatriation was always the end goal.

Collaborative relationships such as these can and do result in compelling research, while also respecting community wishes for repatriation and reburial. But truly collaborative research is complicated and hard to do. Luckily, there are many other examples of researchers and community partners working together in a good way to help show us the way forward.

Take, for example, the shíshálh Archaeological Research Project (sARP). This is a long-term partnership between the shíshálh Nation, the University of Saskatchewan, and the University of Toronto. In 2017, the sARP team worked with the Canadian Museum of History (CMH) to digitally reconstruct the faces of five Ancestors based on their skeletal remains. Community partners gave feedback on appropriate facial expressions, hair styles, and clothing for the Ancestors’ images before they were reburied. This project resulted in scholarly publications, and the reconstructions are now on display both at the CMH and the local tems swiya Museum.

Similarly, at the Manitoba Museum, researchers have worked with Indigenous communities to learn more about Ancestors when they are uncovered by accident or through archaeological work. In these cases, the Elders in these communities take the view that their Ancestors reveal themselves so future generations can learn from and about them. The museum partners with communities to examine and investigate the ancestral remains and any associated belongings, then they collaboratively produce local exhibits and plain-language books that braid together Indigenous Traditional Knowledge with the archaeological and anthropological findings to tell the Ancestors’ stories.

If a community is open to considering anthropological research, consulting scientists have a responsibility to be transparent about all available analytical options and any potential risks.

For example, at the onset of the Journey Home Project in 2006, anthropologists from the University of British Columbia met with Stó:lō Nation community members to hear what they wanted to learn about their Ancestors before they were returned. Researchers came to the next meeting with information on the different methods that might be able to answer those questions. Scientists were open and honest about the possibilities, the processes and samples required, and the limitations of the analyses. It was important to communicate, for example, that the DNA analysis process consumes a small sample of tooth or bone.

Researchers must also be mindful that while they may have been trained to think in terms of specimens and samples, communities think in terms of relatives. Ancestors need to be treated with respect, and appropriate cultural protocols must be followed. This is something museums around the world are integrating into their practice. For example, institutions like the Royal BC Museum in Canada and Te Papa Tongarewa in New Zealand are working directly with descendants to ensure that Ancestors are properly cared for. This includes building spaces like Keeping Places that can allow for ceremonial caretaking and, where appropriate, research before Ancestors are reburied.

Finally (and most importantly), entering a collaborative research relationship means that community partners share control of the project. If a partner chooses to opt out of any aspect of the proposed research, their wishes must be respected. For instance, co-author Katherine has been working collaboratively with Sioux Valley Dakota Nation (SVDN) since 2012 to investigate cemeteries at the Brandon Indian Residential School in Manitoba. Recently, SVDN and university partners put the examination of potential unmarked graves—a key goal of the project—on hold while they reach out to other affected communities. These consultations are important to identify the right way forward.

When it comes to research that involves Ancestors, working in a good way is more important than working quickly.

What these and other examples show us is that repatriation did not end research involving Ancestors. What has ended is the “business-as-usual” approach.

Working collaboratively requires researchers to seriously rethink their understandings of research ownership and control. Communities must be equal partners in the creation, implementation, and dissemination of research projects. This can be difficult—partner communities often have very different goals and ways of thinking from Western-trained scientists—but drawing on multiple lines of evidence actually leads to stronger science.

Collaboration is not new to scientific research—partnerships and team-based projects have a long history in the academy. The only new things are who scientists are collaborating with, and that these new collaborations require us to deliberately shift power to ensure that voices so long excluded are now heard and respected.

Read more, from the archives: “How Museums Can Do More Than Just Repatriate Objects”

This is not to say that everyone will choose to pursue research. In many places, repatriation work continues to be controversial and slow. Too many Ancestors are still housed in colonial institutions, with no plans for their return. Given this, some—perhaps many—descendant communities will not be interested in pursuing scientific research prior to reburial. This is a particularly hard choice for outside researchers to accept, but they must do so to begin redressing the power imbalances in anthropology and archaeology. These disciplines have a difficult history that is rooted in colonialism. Respecting the wishes of descendant communities is the only way to do ethical, responsible, and meaningful research going forward.

Repatriation has indeed transformed the research landscape. It has required a major shift in how Western-trained scientists think about and approach this kind of work. Indigenous scientists and community-based researchers have been doing this work and doing it well for many years already. They’ve shown that community-led repatriation projects can challenge assumptions, build respectful relationships, increase community research capacity, and still meaningfully contribute to scientific discussions. Continuing to focus on repatriation as “the end” of research ignores the alternate collaborative path forward.

Working with and for descendant communities puts research skills and outcomes to work in service of something bigger. Much work remains, but from here we can start to do better together.