What Bigfoot Teaches Us About Public Mistrust of Science

In the late 1960s, Bigfoot seemed to be traipsing all over the Pacific Northwest. Reports of footprints from an 8-foot-tall, bipedal primate came in from Washington to northern California. Chasing these footprints and the creature who made them were a group of amateur naturalists, journalists, and a few credentialed physical anthropologists. Science historian Brian Regal has called this group the monster hunters.

In late 1969, the monster hunters descended on a town in northern Washington. In Bigfoot circles, this would become known as the Bossburg incident. The rivalry among the monster hunters was intense. Everyone wanted to be the first to find, or even capture, a Bigfoot. But they also didn’t want to fall for a hoax.

When the dust finally settled on the small town of Bossburg, we would see the pitfalls of combining science, ego, and arrogance—and how this cocktail promotes pseudoscience and public mistrust of science.

THE ORIGINS OF BIGFOOT PSEUDOSCIENCE

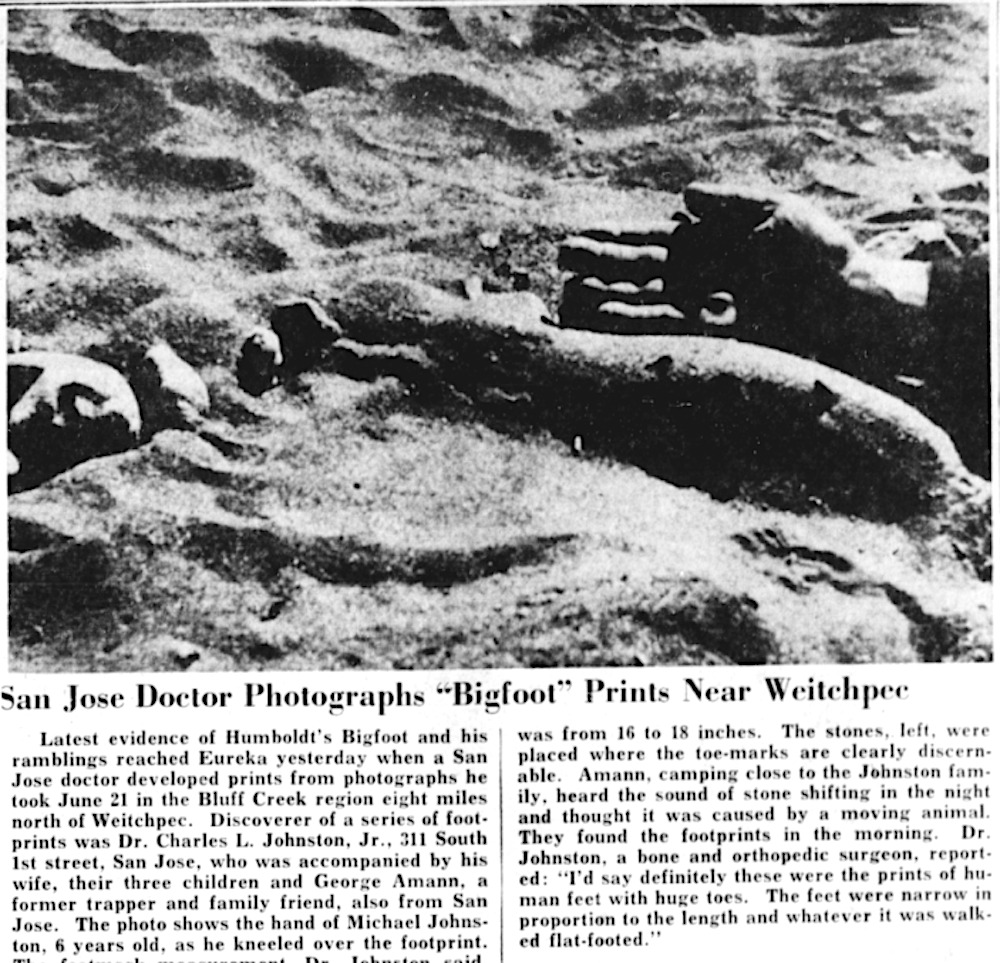

After some early accounts and sightings, the 20th-century Bigfoot frenzy erupted when a set of footprints were found on a construction site managed by Ray Wallace near Bluff Creek, California, in 1958. The prints looked human but were larger and suggested a stride length of between 4 and 10 feet. The creature was purported to be between 8 and 10 feet tall with footprints that could be 18 inches long and 8 inches wide. For reference, my foot that fits a U.S. size 12 shoe measures 9.5 inches long and 4 inches wide.

Over the course of several weeks, more footprints surfaced near Bluff Creek. The construction crew attributed them to a creature they called Bigfoot. Once the media picked up the story, the search was on for North America’s Abominable Snowman.

In 1967, two monster hunters, Roger Patterson and Bob Gimlin, set out on horseback to film Bigfoot. They were once again near Bluff Creek. On October 20, they recorded about a minute of grainy, blurry footage. To this day, the Patterson-Gimlin film is considered by many to be the best evidence of Bigfoot’s existence.

Also known as Sasquatch, Bigfoot sightings have occurred in every U.S. state except Hawaii. And around the world, other clandestine bipeds supposedly roam: Among others, the Yeti climbs the Himalayas, the Almas prowls Russia, and the Yowie lurks in Australia. According to some, our planet is overrun with towering primates.

BIGFOOT HUNTERS IN BOSSBURG

When tracks were found in northern Washington a few years after the Patterson-Gimlin film, everyone came running. A veritable circus of monster hunters and media arrived at the small town of Bossburg, but I will just focus on three: René Dahinden, Grover Krantz, and Ivan Marx.

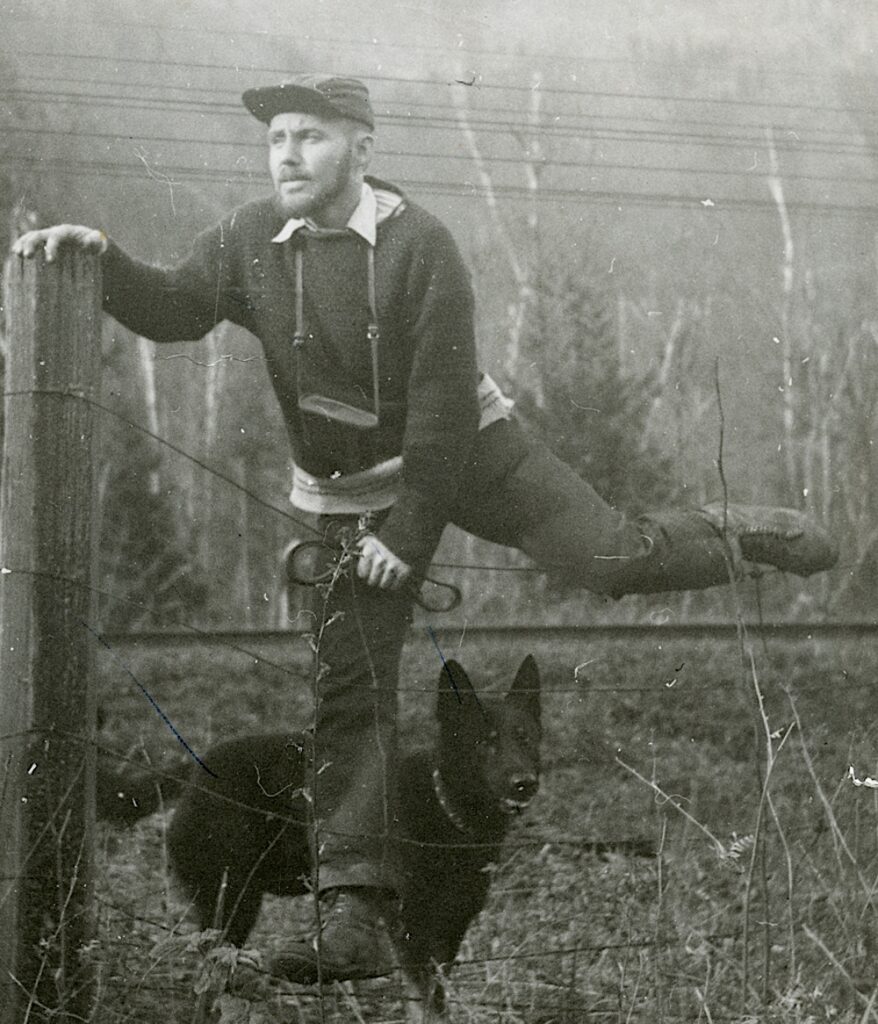

The irascible Swiss Canadian Dahinden was an amateur naturalist who had a reputation in the Bigfoot community as a serious investigator who was suspicious of most people involved in Bigfoot research. A physical anthropologist at Washington State University, Krantz saw himself as bringing real scientific training and acumen to the search for this anomalous primate. Marx, a tracker, trapper, and cougar breeder, had been involved in Bigfoot investigations since the early 1960s.

In November 1969, following up on local rumors, Marx located footprints near the city dump and alerted fellow monster hunters that he had found Bigfoot. Dahinden joined Marx a few weeks later, and the two went searching for more tracks. On December 13, they checked an area where they had left meat out as bait. Marx got out of the car but returned almost immediately, having found footprints in the snow. This trackway comprised 1,089 prints.

When Krantz finally arrived, most of the tracks had melted or been trampled on, but a few were preserved under cardboard and newspaper. These would convince Krantz that Bigfoot was real.

EVIDENCE OR HOAX

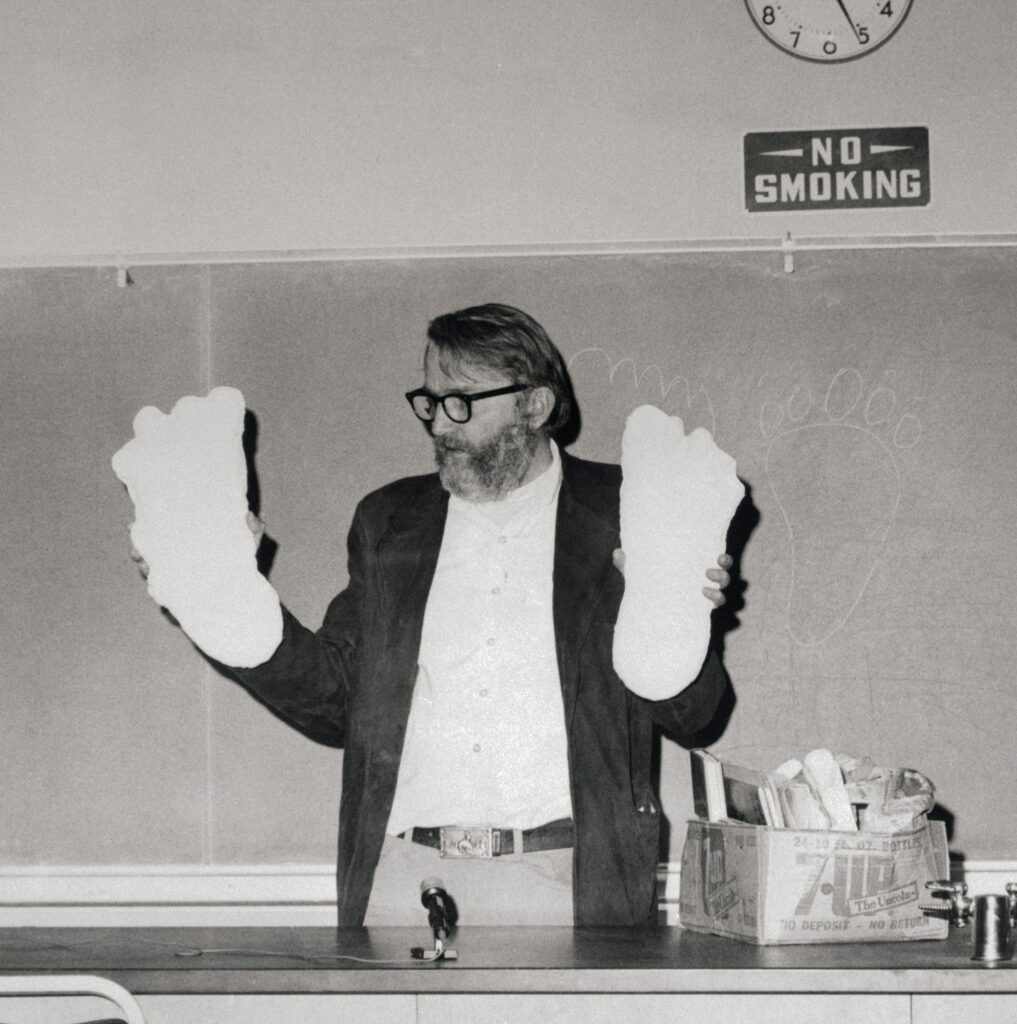

The left foot, like most alleged Bigfoot prints, was about 17 inches long and 7 inches wide. The right foot, however, has curved toes and bulges on the side. As a physical anthropologist trained in anatomy, Krantz believed that the right print’s abnormality was due to a traumatic injury, which led to a deformity in the foot and a severe limp.

He said, “If someone faked [these footprints] with all the subtle hints of anatomy design, he had to be a real genius, an expert at anatomy, very inventive, an original thinker. He had to outclass me in those areas, and I don’t think anyone outclasses me in those areas, at least not since Leonardo da Vinci. So, I say such a person is impossible, therefore the tracks are real.”

These became known as the Cripple Foot tracks.

Unlike Krantz, Dahinden had seen the entire trackway. It started at a river, crossed a railway, road, and fence several times, and ended back at the same river. It was an odd path. Marx also conveniently found Bigfoot evidence at will. Dahinden said of Marx, “It seemed that every time he called, Marx had found something, a handprint here, a footprint there … always something to keep the trail warm.”

A few weeks later, Marx claimed to have filmed the creature. When others viewed the video, some thought it was obviously faked. Evidence surfaced that Marx had recently bought scraps of fur in a neighboring town. Dahinden strongly suspected that Marx also hoaxed the Cripple Foot tracks. But Krantz refused to accept that they were not real.

SLIM CHANCES FOR BIG BIPEDS

What are the chances an 8-foot-tall, bipedal primate lives in North America?

From an ecological perspective, slim. Large-bodied animals eat a lot and then produce mounds of poop. Surely, hikers and naturalists would have encountered Bigfoot droppings then, right? Not to my knowledge. Moreover, no one has ever found bones, roadkill, or other remains from a dead Bigfoot.

What does this episode tell us about the public mistrust of science?

Science purports to be a systematic way of gaining reliable knowledge about the world around us. Science’s authority comes from the fact that it relies on evidence, which can be checked by others to ensure reliability.

Done properly, science is self-correcting. However, the scientific process can break down if individual scientists see themselves, rather than the evidence, as the source of authority. Then, the evidence becomes secondary—or worse, unimportant.

In the Cripple Foot case, Krantz’s estimation of his own intelligence, at least on par with that of da Vinci, blinded him to the evidence that was before him. He believed that his knowledge was so specialized and detailed that it was beyond the capacity of others to understand. He was more like a medieval priest than a scientist.

Dahinden, himself not a credentialed expert, was better able to recognize the evidence for what it was: a hoax. The amateur Dahinden acted more scientifically than the Ph.D.-holding scientist, Krantz.

HUBRIS AND PUBLIC MISTRUST

The Bossburg incident serves as a warning against hubris among scientists. When the scientist becomes more important than the subject being studied or the evidence being gathered, they are no longer practicing science or producing reliable and useful knowledge.

And scientific or academic hubris is not limited to claiming genius-level intelligence. It can also manifest in opaque language. In later years, Krantz would say that he had two secret tests that could determine whether a footprint was real. He never revealed them. Ultimately, not even the other monster hunters trusted him.

When scientists behave as Krantz did, as if they possess secret knowledge that is somehow unobtainable or incomprehensible to those without specialized training, they open the door to public mistrust.

The public should have trust in science. It is the most efficiently reliable way to learn about the world around us. But let Bigfoot be a reminder that scientists are not more important than the quality and accessibility of their science.