The Colonial Roots of Peru’s Troubles

Last month, Peru’s Ministry of Culture closed the famous Inca citadel, Machu Picchu, following a series of violent protests. The turmoil, which has resulted in the deaths of at least 60 people, followed former President Pedro Castillo’s arrest and impeachment in December—what supporters and some other nations have called a coup. On February 15, Machu Picchu reopened, but the political tumult persists.

Although authorities claim Machu Picchu was closed for safety concerns, as an archaeologist who has worked in Peru since 2010, I see the move as deeply symbolic. Those in power closed access to the period in Peru’s past when much of today’s turmoil originated, the period of colonization that began with the conquest of the Inca Empire by Spain in A.D. 1532.

To understand the origins of what might seem like isolated political unrest, we need to look to the oppressive, extractive practices enacted during the Spanish colonial period, which dates from A.D. 1532–1800.

PERUVIAN COLONIAL MINES

As a historical archaeologist, I research the legacies of Spanish colonial policies in Peru. To better understand forced labor during this period, I examine historic documents and conduct archaeological excavations in Peruvian colonial mines and refineries.

Since 2016, I have worked in Puno, Peru, a city that sits on the banks of Lake Titicaca. The Puno region has been hit especially hard during the recent upheaval, with more than 17 people killed and 68 injured during clashes with security forces. The area has seen massive protests, road blockades, airport closures, and the halting of central economic activities.

Meanwhile, the mining industry, entrenched in corrupt government dealings and unfair labor practices, continues on, so far largely unaffected by the unrest.

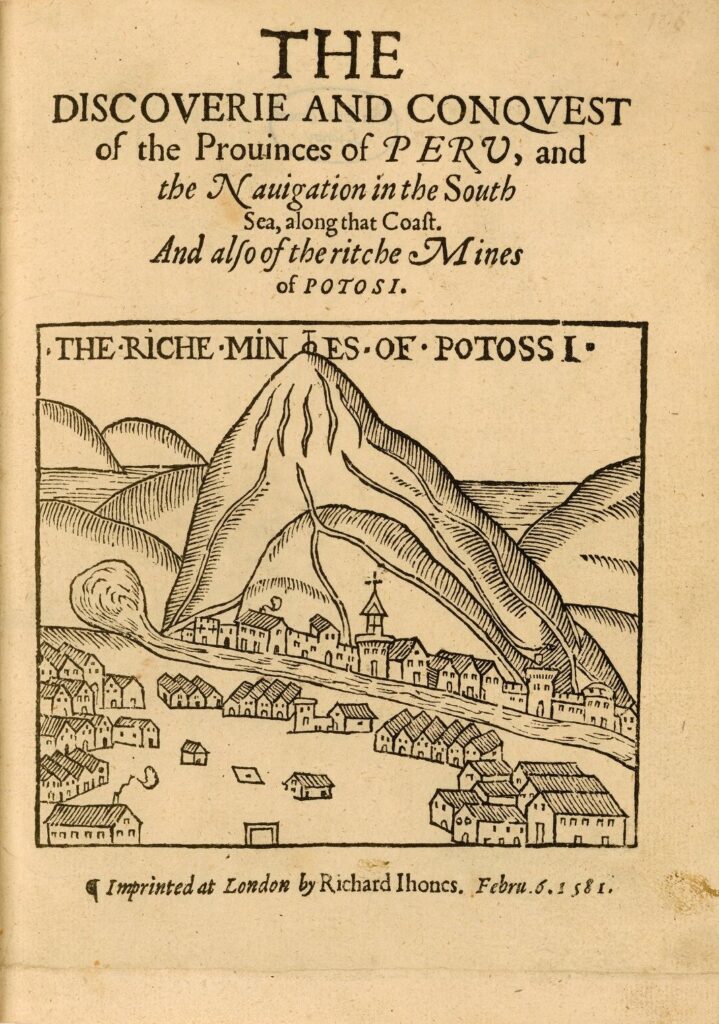

As it is today, mining was an important part of Peru’s economy in the past. Silver funded Spain’s colonial wars of expansion and decorated its Catholic churches. The metal came from silver deposits in Peru and Bolivia, some of the richest on earth. Bolivia’s Potosí mines alone produced over half of the world’s silver in the first 100 years of its existence. The region’s mines were so successful, the Spanish peso became the first global currency by the end of the 18th century.

The silver was extracted, refined, and transported on the backs of Indigenous and African laborers. The exploitation of these workers was the foundation of Spanish colonial wealth for centuries.

Indigenous laborers, called mitayos, were drafted and forced to work in Peruvian colonial mines and refineries under the mita system. More than 8 million workers likely died in these work sites, which became known as the “mines of death.”

In a recent study of the silver refinery of Trapiche Itapalluni near Puno, our team identified a series of exploitative, colonial labor policies that harmed Indigenous people and the environment. [1] [1] The research was part of the Trapiche Archaeology Project or El Proyecto Arqueológico con Excavaciones Trapiche, which has been co-directed by Karen Durand Cáceres, Jorge Rosas Fernandez, and Sarah Kelloway. Today similar practices continue to bring about inequality, exploitation, and environmental destruction for Peruvians.

Collaborating with local Indigenous communities, we found traces of toxic metals, including lead and mercury, left in the soils at the Trapiche refinery. These still-toxic sites sit near Indigenous settlements and water sources.

I also examined colonial documents that described refinery workers being forced to mix a slurry of ground silver and mercury with their bare feet, as well as to heat the mixture in ovens, breathing in toxic fumes. Some workers were crushed by grinding stones and in tunnel collapses. Analysis of human remains from mass graves indicate that colonial miners suffered interpersonal violence, backbreaking work, and child labor. Today Peruvian mine workers report many of the same conditions and hazards.

In addition to being unsafe, Peruvian colonial mines and refineries relied on coercive labor policies to force people to work, usually without pay. According to historic census records, many people were sent to work in the mines against their will under the mita draft. Others worked to pay off debts. Some were enslaved.

In Puno, historical documents indicate that enslaved Africans, mitayos, debtors, and free laborers all toiled in mines and refineries. Jewelry and shawl pins that my team uncovered during excavations at Trapiche reveal that families worked at these places together. These items provide additional evidence of child labor, which still occurs in Peru’s mines.

While facing danger and oppression, past workers were able to make some profit on the side. Colonial-era miners took advantage of free days to work in the mines independently, as they were allowed to take any ore they found. Often, they would hide rich silver veins from Spanish administrators to mine themselves later. Other illicit activities that circumvented government regulations included clandestine refining and smuggling of silver.

Similarly, today’s Peruvians illegally extract or refine ore on their own, by hand and independent of large corporations. This so-called artisanal mining may be people’s only means to supplement their income and make a living—especially during recent periods of climate change–fueled drought, the pandemic, and rising inflation costs, when no other options have been available.

THE LEGACIES OF COLONIAL exploitation

Today’s Peru is not post-colonial. Exploitative labor practices like those initiated during the Spanish colonial period endure. This can be seen in multinational corporate mining, the dispossession of Indigenous lands, and the destruction of the environment.

The modern Peruvian state is failing to protect its people and environment from exploitative, extractive industries. And the current protesters know it. The protesting Peruvians, many from rural Indigenous communities, demand action to address government corruption, inequality, inflation, climate change, and environmental degradation.

To be sure, some believe the current political crisis has no historical impetus. In White, elite Peruvian circles in the capital city of Lima, many blame the rural Indigenous communities themselves for their poverty and inequality. Others, such as Peru’s new president (and Castillo’s former vice president), Dina Boluarte, blame drug traffickers, communists, and the illegal mining industry for the current violence. However, these issues grew from the colonial experience, and we must continue to advance decolonizing Peru if they are to be truly addressed.

As the number of exploited Peruvian workers continues to rise, we can look to the colonial past to better understand the roots of the country’s extractive labor practices. These long-standing economic activities have accrued enormous environmental and social debts. The protestors, and international onlookers like me, say it’s time the government takes responsibility for those debts.

Correction: March 7, 2023

An earlier version of this article included an additional image and did not name the Trapiche Archaeology Project and its directors.