When Disaster Tests the Strength of Human Cooperation

Judith grew up on the southern flank of Tungurahua, a towering presence in the Andean highlands of Ecuador. [1] [1] All names have been changed to protect people’s privacy. When the volcano erupted in 2006, just seven years after a prior large eruption, it blasted ash into Judith’s home village of Manzano and a dozen neighboring villages. Deadly flows of pyroclastic material—a mix of ash, lava, and gases—streamed down the slopes. Judith and a few thousand other villagers had little choice but to flee.

Farther downhill, Judith and others built a camp beneath the high hill known as El Montirón, which she called “our salvation” thanks to the protection it provided. For weeks, people organized to take care of one another.

“We came together as a community,” she said. Villagers cooked communal meals, sharing and distributing whatever they had: “rice, sugar, tuna, everything.”

Judith was talking about a minga. This practice of cooperation, common to Indigenous and campesino communities in the Andes, often takes the form of rotating labor to work on farms and build collective infrastructures such as roads or irrigation canals.

Some observers might see Judith’s story of minga-style mutual aid in the shadow of Tungurahua as an example of the spontaneous altruism, or communitas, that often arises in the face of disaster. Proponents of this idea argue that when physical and social structures break down in a catastrophe, people come together across differences to cooperate and look out for one another. Writer Rebecca Solnit refers to this kind of communal support as a “paradise built in hell.”

For many, this prospect is alluring—a vision of the world that speaks to the fundamental goodness of humanity. Contrast this thinking with other popular notions that imagine humans as naturally selfish individuals driven to seek maximum gain from minimal output.

But as an anthropologist who has spent more than 10 years researching disasters and cooperation in Ecuador, I see minga—and humans in general—as far more complex. Simply put, human nature, if we can even speak of such a thing, is neither essentially altruistic nor essentially selfish.

What matters more in determining whether and how a community will cooperatively respond to and recover from a disaster are the institutions that guide and are guided by human action.

WHAT IS MINGA?

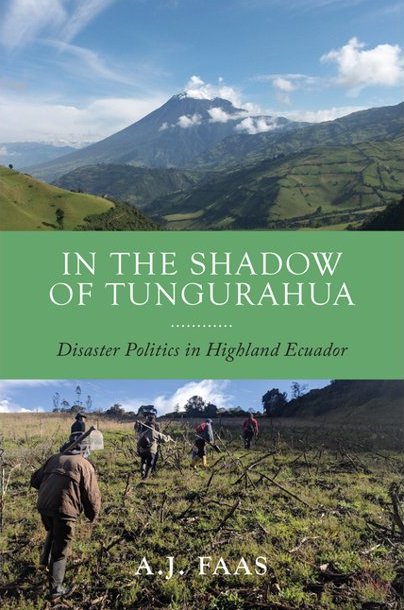

In my 2022 book, In the Shadow of Tungurahua: Disaster Politics in Highland Ecuador, I examine the history and tradition of minga cooperative work parties. Minga showed up everywhere in my research—in Judith’s home village of Manzano, in the nearby campesino communities of Canton Penipe, and in the resettlement communities built for people displaced following the eruptions of Tungurahua in 1999 and 2006.

Judith described minga to me as “the union of the whole community to realize a planned work for the benefit of the community.”

Yet the more I learned about minga, the harder it was for me to match the diversity of practices I observed with a singular term. In large part, that’s because minga’s history as a tool of forced labor seems to directly contradict its current reputation as a strategy for collective empowerment.

Tracing the origin of minga is a bit like trying to find the start of wind. The earliest available evidence of the practice finds that local chieftains in the Andes were organizing collective labor parties even prior to the formation of the Inca Empire in the 13th century. Over the course of the 14th and 15th centuries, the Inca systematized minga as an instrument of empire building, extracting tribute from commoners on a grand scale. But they recognized an important moral dimension of minga: Rulers reciprocated by granting the products of minga labor—irrigation canals, roads, storehouses, and surplus grains—to their subjects.

Following the Spanish conquest in the early 16th century, colonizers in what is today Ecuador (as they did throughout the Andes) transformed minga into a violent instrument of forced labor and control for mining precious metals and state building. Indigenous men were conscripted to work in silver mines to complete grueling labor quotas, or tareas, few could meet. Throughout the colonial period, colonizers exploited minga labor and relocated Indigenous peoples into fixed settlements where they could more readily be subjugated and controlled.

Following Ecuador’s independence in 1822, minga remained a central institution of the state and the highland hacienda (plantation) economy, where large landholders bound Indigenous peoples and the rural poor to labor in perpetual debt in service of state infrastructure and private profit. In many ways, aspects of this system endure in the present in various forms.

However, since the mid-20th century, village councils have been the primary organizers of mingas, usually to create and maintain local infrastructure. One adult per household is expected to volunteer for these work parties to earn a raya (attendance credit). A household’s reputation and eligibility for shared services and support—their good standing in the community—depend on their regular participation.

Minga does not happen despite inequality but because of it.

Those in power, including the Ecuadorian government and nongovernmental organizations, also frequently call upon minga labor for infrastructure projects. These organizations are then expected to “reciprocate” by providing materials and technical guidance to laborers.

In other words, minga continues to be a framework that local and state leaders and other organizations use to recruit and at times compel citizens to labor, particularly rural campesinos and Indigenous peoples. But minga is also a way for citizens, in turn, to both organize their communities and demand reciprocity from the government and NGOs. This history helps explain the complex dynamics that ended up developing among villagers tasked with rebuilding after Tungurahua’s eruption.

TWO WAYS TO MINGA

By the time I first arrived in Ecuador in 2009, people displaced following the 2006 eruptions of Tungurahua had just moved into several resettlements in the central township of Penipe, about 10 kilometers from the volcano’s slopes. Some were in government-built developments with no land or economic resources for people to make a living. But one site, Pusuca, consisted of 45 houses built by the Ecuadorian NGO Fundación Esquel and included farmland for resettlers. At this site, villagers provided the initial labor to build the resettlements. People were organized into mandatory minga work parties by the agencies designing and managing construction.

But eventually, many of the resettlers wanted to return to their farms and home villages. For two years (2009 and 2011), I accompanied those who returned to Manzano, where I witnessed the community spirit of minga Judith spoke of. People worked to rebuild with little direction beyond the village president calling on them to join the work party on a given day. I regularly joined small gangs of campesinos leapfrogging over one another to repair collective roads and irrigation canals necessary to their livelihoods. Each person worked according to their ability and generally at their own pace, earning the same raya for a day’s work. These were generally joyful and convivial affairs where people labored without complaint, told stories and jokes, and took advantage of midday meal breaks to share food and socialize.

As my friend Samuel explained, minga “is a common obligation that must be regularly renewed.” It was what had enabled the village of Manzano to survive.

But minga, I realized, often looked quite different for those who remained in the resettlement communities. People also continued the practice in Pusuca, but it was mandatory and more strictly enforced. While they might be organized once or twice a month in Manzano, people were working arduous mingas once or twice a week in Pusuca. Most of these labor parties focused on digging and constructing a nearly 10-kilometer irrigation canal. These projects were directed not by villagers themselves but by engineers employed by Fundación Esquel.

Rather than working each to their ability, as in their home villages, people in Pusuca struggled to complete tareas, similar to the colonial-era labor quotas for mingas. The accounting of tareas and rayas was often acrimonious, with villagers scrutinizing the deservingness of each neighbor with an exacting hypervigilance.

SUPPORTING COOPERATION

As I learned over time, the debates in Pusuca over fairness nevertheless served a greater purpose. They were not simply interpersonal quarrels revealing people to be ultimately selfish, individualistic actors.

Instead, they were also part of the institution of minga and its emphasis on the collective. When villagers argued about who did and did not deserve a raya for minga participation, they were ultimately demanding greater transparency and fairness from those in power. The villagers were holding state officials and NGO administrators—whose operations are often hopelessly esoteric—accountable. On several occasions, I observed an NGO adjust their expectations for work quotas and revise their accounting of people’s rayas in response to these complaints.

Read more from the archives: “How to ‘Co-Live’ With a Natural Hazard.”

What does all this mean for how we understand cooperation in disasters? The answers are surprising. First, my work points to how a society’s institutions can help either sustain or thwart cooperation. Minga is an institution with a storied history, rules, and values that guide action—but it’s not predetermined what those actions will be.

Second, and importantly, minga is a practice predicated on unequal power relations. Minga does not happen despite inequality but because of it. But—and this is truly remarkable—when those in power demanded that villagers labor to rebuild after the volcanic eruption, the institution of minga also guaranteed that governing bodies adhere to an ethics of fairness, reciprocity, and collective good. Through minga, villagers were able to force state officials and NGO administrators to provide necessary resources for their vital infrastructures and livelihoods.

EXPORTING MINGA?

Friends, colleagues, and students outside of Ecuador often ask me how to bring minga mutual aid to respond to disasters in their countries. While I am sure that many of my friends in Ecuador would be happy to share and teach those outside of their villages about minga, my answer is that minga is their institution, their set of tools.

Look instead to mutual aid organizations that may exist closer to home. (Those in the U.S. can start with groups such as Mutual Aid Disaster Relief or Mutual Aid Hub.) Help reframe, repurpose, and strengthen the institutions that support social and environmental justice in your society.

These can be formal or informal networks or organizations—but they need to be cultivated and kept vital before a disaster happens. Short-term bursts of community support in the wake of a disaster are, of course, helpful, but my research in Ecuador suggests that preventing, responding to, and recovering from disasters is more successful if we create social institutions that can flex and adjust to longer-range problems and support fairer, more just ways of working together for a common purpose.

In other words, the mutual aid that works in a disaster and lasts long after does not rely on any preconceived notions of an altruistic “human nature.” Rather, successful organizing reflects practices and discourses of mutual aid that start long before they are needed.

When my friend Judith and her neighbors in the shadow of Tungurahua looked for ways to help one another in their time of need, they had minga as their tool for the job. My work suggests that the rest of us should invest in the tools we might take up in our time of need.