Digging Into the Myth of Timbuktu

Sometime around 1 o’clock in the afternoon on April 19, 1828, René Caillié emerged from the dark hull of the slave ship that he had boarded weeks before. Eager to disembark and escape the “prison” that he had uncomfortably shared with bundles of rice, millet, cotton, honey, vegetable butter, and fellow travelers, Caillié mounted the first available canoe and glided toward shore.

By the next afternoon, after making his way through the dusty Sahelian streets of the port city and traveling north, he became the first European to see West Africa’s Timbuktu and live to recount his tale.

Not yet 30 years old, Caillié had achieved one of the most elusive feats of early modern exploration, succeeding where numerous generations of European explorers had either given up or died along the way. His improbable success was likely rooted in his unusual approach to exploration. Unlike the typically large Victorian expeditions, with military escorts and long supply chains, Caillié maintained a more modest contingent, originally traveling with a single companion—and later, on his own. Having left home at the age of 16, he was a skilled traveler. He spent years exploring West Africa, studying the Koran, mastering Arabic, and learning the local customs. He eventually made his move on Timbuktu traveling undercover as a poor Egyptian named Abdallahi, explaining to others that he had been kidnapped by the French and was merely attempting to return home.

Numerous thrill seekers, colonial agents, and missionaries had all taken their shot at the fabled city, which was glorified at the time for its political and scholarly achievements, as well as the caravans of gold that passed through its gates. The fascination with Timbuktu, which is in present-day Mali, was such that both the French Société de Géographie and the British Royal African Society sponsored expeditions into the heart of the Sahara, with the former even announcing a prize of 10,000 francs in 1824 to anyone who returned with a firsthand account of Timbuktu. Caillié eventually claimed this prize.

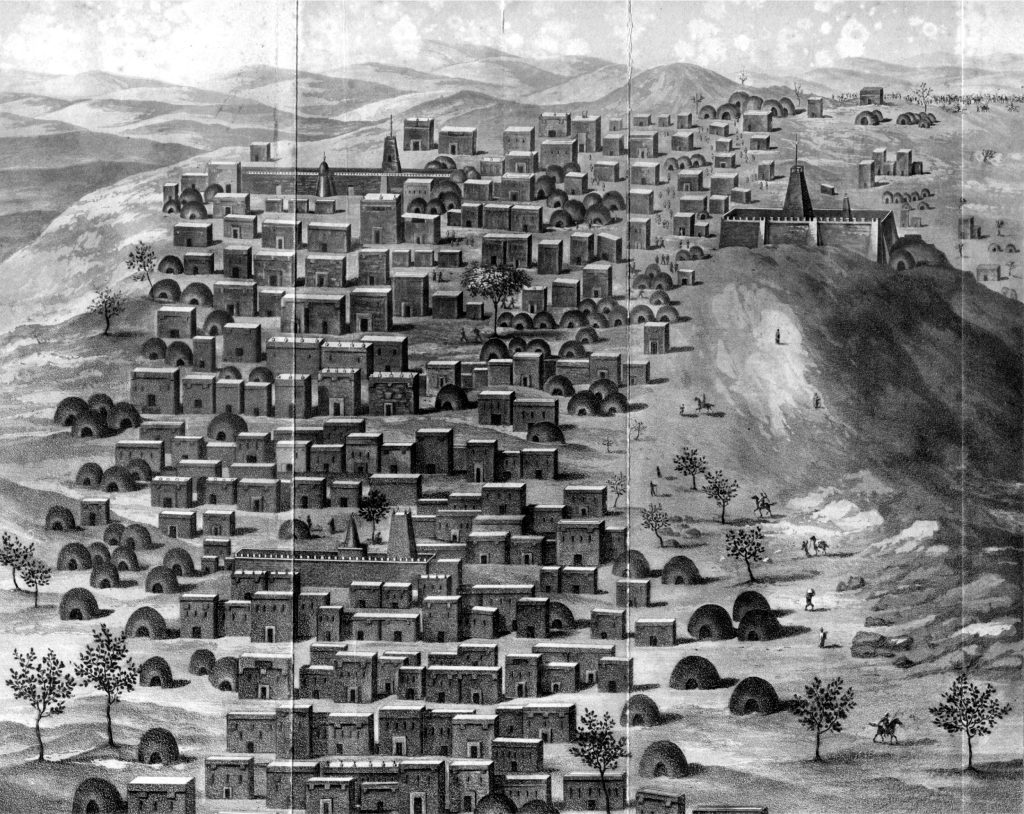

But Caillié reported that Timbuktu was a small, provincial town with “nothing but a mass of ill-looking houses, built of earth”—an observation that may have contributed to a shift in European perspectives on sub-Saharan Africa toward a more paternalistic and elitist stance. During the latter part of the 19th century, sub-Saharan Africa came to be seen as a region that lacked a history worth knowing—for its people were viewed as having made no significant social, political, or technological advancements. This, despite the fact that Caillié had stepped off the slave ship and walked to a city that we now know had seen more than 2,500 years of human settlement and was a center of both learning and commerce from the mid-14th century through the beginning of the 17th century.

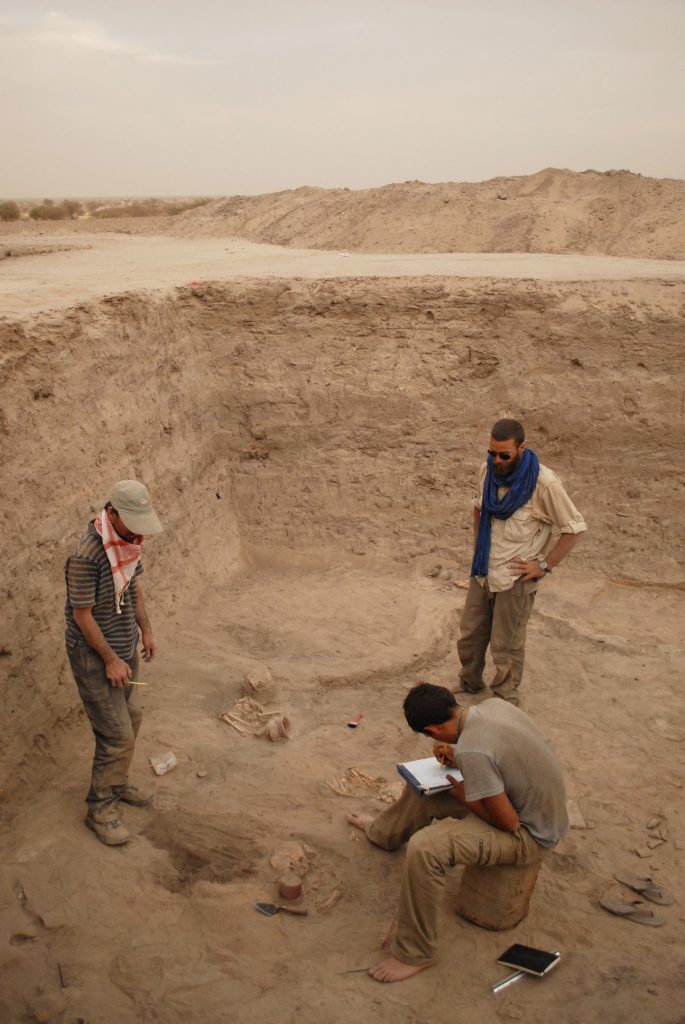

Although the oral history of the region suggested that Timbuktu was first settled by Tuareg nomads in the 12th century, preliminary archaeological research during the 1980s suggested a much earlier occupation. In 2008, a team of archaeologists from Yale University and the Malian Ministry of Culture’s Direction Nationale du Patrimoine Culturel set out to investigate the murky origins of the fabled city.

Led by archaeologist Douglas Post Park, a descendent of the famed Scottish explorer Mungo Park, the research team eventually located hundreds of settlements dating at least as far back as 500 B.C. As co-director of the project, I worked on Park’s team for three seasons of fieldwork, surveying, excavating, and analyzing thousands of ceramic sherds. Our findings pushed back the age of Timbuktu by more than 1,500 years and revealed a remarkable and unique type of urban landscape in which people structured their lives around the pulses of the Niger River’s flood seasons. These pulses were connected to many aspects of daily life, such as rice and millet farming; sheep, goat, and cattle herding; and of course, hunting and fishing. When the floodwaters inundated the floodplain, people moved to higher ground, likely clustering together in extended family units. As the waters receded, people again spread out across the landscape, planting their crops in the rejuvenated soils. The communities living in the region likely developed this routine somewhere around 200 B.C. and continued to thrive within this social structure until around A.D. 900.

The research by Park’s team is just one of a growing number of examples that suggest the typical model for ancient cities might not be as typical as once believed. The monumental architecture, concentrated wealth, and dynastic kings central to ancient cities like Uruk (in present-day Iraq) and Memphis, Egypt, have defined the archetypal early city. But at Timbuktu, the urban area developed into something unique. From the 1,100-year span during which this society thrived, there is so far no evidence of overt hierarchical structures. Power was conveyed in ways that were very different from those of despotic rulers in Mesopotamia, Egypt, or other urban centers in the ancient world.

What is clear, then, is that far from being a region without a history, sub-Saharan Africa has a deep and complex past of its own. Its civilizations were not the result of Egyptian, North African, or European influence.

Yet the European sentiment that this region had no history wasn’t simply about ignorance or a dashed romanticism—it was also politically convenient, as it justified a colonial campaign to help bring “civilization” to African peoples. Timbuktu itself was formally incorporated into the French Empire by 1894.

It appears that a circular logic was at play: If there was no history to be found in sub-Saharan Africa, there was no reason to look for it—and if you didn’t look, you wouldn’t find any history. As a result, although British archaeologist and Egyptologist Sir William Flinders Petrie had first excavated in Egypt as early as 1880, nearly a century would pass before sub-Saharan Africa began to receive much attention from Western archaeologists. Following World War II, however, as the postcolonial period commenced, archaeology began to emerge as an avenue for African nationalism to take root. In fact, Mali’s first democratically elected president, Alpha Oumar Konaré, was a trained archaeologist.

When Caillié wandered through the streets of Timbuktu, he did not see a city in which the rooftops were lined with gold—as was the popular European image at the time. But he walked through a city that had a remarkable history. His humble description of Timbuktu may have disappointed some in the learned societies of 19th-century Paris and London, but modern archaeological research throughout West Africa is uncovering evidence of large urban centers, unique social and political institutions, long-distance trade networks, and powerful empires.

Cities such as Timbuktu had a uniquely West African flavor—and they developed without the external influences of “more advanced” societies, in contradiction to what many Europeans in the 19th and 20th centuries believed.

While the riches of Timbuktu are no longer symbolized by caravans of gold, there is still a wealth of information buried beneath its soil. We just have to look.