“Throw Me Something, Mister!”

The parade crowds were already forming as I held on to my oversized cowboy hat and made my way to the krewe’s meeting spot. I could see our float in the distance: a 10-foot-tall papier-mâché James Brown, holding a gigantic, cartoonish microphone and wearing a paisley robe that had been revamped into pure funk. It was Mardi Gras time!

My krewe had an hour before we assumed parade formation, which was just enough time for a quick bite and a stiff drink. On this chilly night in January, costumed revelers and members of other krewes were huddled together with drinks in hand, laughing raucously. I recognized some of my fellow krewe members by their hand-sewn, silver-sequined capes and their red, white, and blue clothing—all part of our krewe’s 2016 theme: “James Brown—Funky President.”

When our krewe gathered, we created a magnificent sight: 40 people of a variety of ethnicities, marching and dancing on a 3-hour, 5-mile journey through the Faubourg Marigny and into the French Quarter. The giant sound system boomed with James Brown’s funkiest hits as we gathered our gifts to hand out to the crowd. Over the last month, we had upcycled and decorated tokens to match the funky theme: bejeweled small pendants with portraits of James Brown, magnets, necklaces, and stacks of 45 rpm records repurposed as psychedelic political propaganda for President James Brown.

Our krewe is one of the several dozen social clubs that have formed the backbone of New Orleans’ Mardi Gras culture for the last 150 years. I am part of the Krewe of King James—The Super Bad Sex Machine Strollers, which is a subgroup of KreweDelusion, an umbrella organization containing about 15 subkrewes like ours. Each has a different theme, for example, Krewe de Seuss is dedicated to imagery of Dr. Seuss while Krewe du Jieux has a distinctly Hebrew flavor. Each krewe and its subkrewes have their own unique character and ethos, which they showcase in parades through their motifs and social satire, thereby taking their place in the multilayered gumbo of New Orleans culture.

These parades are the drumbeat at the heart of Mardi Gras. As an ethnographic filmmaker, I have come to understand how Mardi Gras celebrants share a cultural thread with societies around the world, from Thai monks to Trobriand Islanders. They all depend on a gift economy.

Today, most societies acquire things through a market economy in which people buy, sell, or trade goods and services. In a gift economy, people give items away without the explicit expectation of something in return. Gifts are offered in a spirit of generosity and community, and they strengthen the bonds between giver and receiver in a way normal currency can’t.

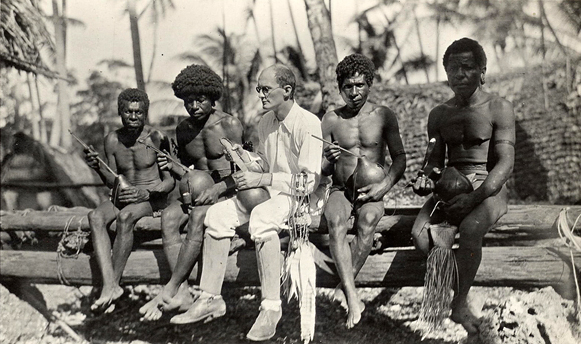

The most common gift economy is one in which gifts serve to elevate social status. One of the first to be explored in-depth was an inter-island exchange network called the Kula ring, which thrived in the Trobriand Islands off the east coast of Papua New Guinea. The Kula ring, famously described by anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski during World War I, is a ceremonial system in which male participants, typically, canoe great distances, sometimes hundreds of miles, across the ocean to exchange necklaces and armbands made of shells. Malinowski discovered that the men were not trading for wealth but for prestige, with a goal that was social rather than material.

In a similar vein, other anthropologists describe potlatch ceremonies in the Pacific Northwest in which someone hosts a massive giveaway of art, clothing, weapons, food, boats, houses, and more, sometimes even destroying valuable objects—to gain social status.

Not all gift economies trade in prestige. In Thailand, Theravada Buddhist monks seek alms from believers, primarily in the form of food, and the givers aim to earn merit that will lead to a better life. In this case, the monks provide spiritual support for the community and, in return, the community provides them with the necessary sustenance.

New Orleans has a complex racial and religious history. Historically, color lines were more blurred there than in other regions of the South. Slavery had a different makeup compared to elsewhere in the country, since it was influenced by 18th-century French and Spanish regimes. More free blacks lived in Louisiana than elsewhere in the South, and slaves were often treated more humanely (in general). They could buy their freedom, marry, and participate in the Catholic Church. They were more literate and were more likely to form interracial relationships. Many slaves added Voodoo traditions to the culture, which sometimes were blended with Catholic rituals. Yet, despite this distinctive amalgam of race, culture, and belief, the city remains culturally divided along a racial spectrum, with white, wealthy, uptown dwellers geographically separated from the poorer black areas such as Tremé and the Ninth Ward.

Mardi Gras bridges these differences through satire, revelry, and ritual. During the approximately three-week celebration, the exchange of gifts—food, drinks, trinkets, and more intricate pieces such as our krewe’s 45 rpm records—acts as the glue that binds New Orleans together, creating a sense of community and belonging.

The Mardi Gras season marks the lead-up to Lent, a 40-day Christian period of prayer, fasting, atonement, and penance that concludes at Easter. Lent’s ascetic denial of certain pleasures, especially meat and alcohol, led Mardi Gras to become a celebration of overindulgence and excess. For locals, though, Mardi Gras is more than an excuse to party. A tradition of sharing and giving is woven throughout its fabric. And so, for a few weeks each year, a rich, colorful, delicious gift economy is added to the usual one of dollars and cents.

Gifting takes all forms, but food and drink are especially popular. The most iconic gift of the season may be the king cake, which is present at most Mardi Gras gatherings. The king cake is a sugary, cinnamon-roll creation, usually shaped into a ring and decorated in Mardi Gras purple, green, and gold. The tradition associated with king cakes is a mutual trade known as a reciprocal exchange, and it is surprisingly similar to that of the Kula ring. In the Trobriand Islands, the gift of a red shell necklace obliged the recipient to give back a white shell armband. In New Orleans, a small plastic baby is hidden somewhere inside the cake. Some believe the doll represents baby Jesus, and it continues a French tradition of hiding surprises in cakes for Lent. In the spirit of reciprocity, the guest served the slice with the baby inside must host the next party, or at least buy the next cake.

The Box of Wine parade, on the other hand, requires no reciprocity. Unlike other parades, it is open to all who march in the spirit of Bacchanalia—not just members of a particular krewe. Each participant carries a box of wine and distributes small portions to an appreciative, thirsty crowd. These glugs of wine are pure gifts. Marchers desire nothing in return other than a smile and a thank you.

It is during the krewe parades that gift giving reaches its peak. In the tourist-heavy French Quarter, visitors typically see a commercialized and risqué version of our celebrations, steeped in booze and plastic beads. But over the weeks leading up to Fat Tuesday, the last day of the Mardi Gras season, there are dozens of parades. Each night, crowds of locals—children and adults alike—gather to BBQ, socialize, and promenade up and down St. Charles Avenue.

Beyond the social spectacle and the clever floats, parade watchers come for the gifts that are tossed to the crowds. Outside New Orleans, the most famous of these so-called “throws” are the beads, which come in all shapes, sizes, and colors. It is a tradition that stretches back to the 1840s, when parade riders threw precious and beautiful glass beads. According to some historians, this practice had even earlier roots in pre-Lenten festivals in Renaissance Europe, when villagers would hurl objects into the crowd during ale- and mead-filled binges. Today, beads act as cheap currency to keep everyone involved with the party. Revelers often collect dozens and hang them around their necks. But while the shiny strands are highly desired during a parade, they have no lasting cultural value.

Inside the local New Orleans’ Mardi Gras gift economy, krewe-specific throws come in the form of trinkets, toys, or medallions, the most special of which are given to locals who understand their value and will be more likely to save and cherish them. These handmade throws provide opportunities for social interaction, opening a door for conversations between people from the area who might not otherwise meet.

The Krewe of Zulu is one of the oldest African-American social clubs in the United States, and they use African tribal imagery, as well as blackface and Zoot suits, to poke fun at stereotypes and make a statement. Blackface, theatrical make-up used to mimic African-Americans, and Zoot suits, oversized baggy suits popularized in jazz clubs of the 1940s, are examples of historically pejorative imagery of African-Americans in American society. By mimicking these cultural tropes in their parade, the Krewe of Zulu turns them into a source of cultural pride. Their signature handmade throws are individually decorated coconuts—beautiful and highly sought-after cultural artifacts. Even President Obama was presented with his own Zulu coconut on Zulu’s 100th anniversary.

During the Zulu parade, crowd members parlay personal connections with krewe marchers to get multiple coconuts, which they then pass out to other spectators. The coconuts act as a cultural currency: those who have them become a conduit, allowing the valuable throws to land in the hands of people who otherwise might not get one. You will often see African-American men re-gifting coconuts to white attendees, making friends, sharing, and bridging the gap between white and black cultures in New Orleans.

One of the most popular parades is the Krewe of Muses, an all-female group whose signature throws are upcycled shoes—often high heels—that krewe members elaborately bedazzle. They are the most coveted throw in all of Mardi Gras. The Muses also toss ceramic medallions, which are rarer than normal beads and adorned with fun, creative designs that incorporate the year and the krewe’s name. One year, after I caught a Muses sneaker medallion, a young man saw me holding it and begged me to trade it for a strand of beads. After a brief hesitation, I realized I was happy to pass it to someone else who would also enjoy it. Transactions like these strengthen the bonds within our community, engendering a goodwill that lasts throughout Mardi Gras and beyond.

The importance of giving for its own sake, rather than for prestige or other benefits, is emphasized by krewe anonymity. Mardi Gras law requires that krewe members wear masks during their parades. This creates an important dynamic: the receiver does not know who the gift giver is. No personal reciprocity is expected. The member gives on behalf of the entire krewe, and, in return, they receive the adulation and excitement of the crowds and their support for the krewe system, which by extension supports the social structure of the entire New Orleans community.

The parades enchant us all with their spectacle—marchers and spectators alike. Masked and costumed krewes ride on glow-in-the-dark floats, accompanied by a steady stream of music, beads, toys, coconuts, and shoes tossed to the deliriously happy crowds. Here, Mardi Gras rivals Christmas for its sheer bounty.

The crowds roared as I marched and danced with my krewe through the crowded streets. A slightly tipsy, older onlooker danced along with us and cried out, “This is the best float I have ever seen!” Our float captain Pamela gifted him a necklace with James Brown’s portrait. Thousands of people gyrated along to the funky music, soaking up the atmosphere we worked so hard to create and flashing huge smiles when we pulled out records to give away.

Such gifts unite communities. As with every Mardi Gras parade in New Orleans, the onlookers were people of all ages, colors, and income levels united in their love of the bizarre, of music and dance, and of the special gifts that leave enduring memories of this night—and this city and its people—for years to come.