How Will We Remember Coal?

This article was originally published at Platypus, the blog of the Committee for the Anthropology of Science, Technology, and Computing, and has been republished with permission.

As the U.S. moves toward greener energy futures, how we remember—or do not remember—coal has significant implications for how we create more just energy transitions.

Coal maintains a persistent but increasingly unstable role in the U.S. economy today. Earlier this year, the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) came out in support of President Joe Biden’s massive infrastructure plan, likely because it extended a lifeline to mines that produced high-quality metallurgical or “coking” coal used in steel manufacture. They did so because the plan promised jobs to miners who would be displaced by the administration’s commitment to decreasing coal production for energy. U.S. coal production levels have reached their lowest point since 1965, and the number of producing coal mines has decreased 62 percent since 2008.

New metallurgical mines, however, continue to open. As a case in point, the New Elk Mine in southern Colorado fired up again in June, with plans to ship nearly 3 million tons of coal per year to overseas steel-making plants. The mine’s reopening was noteworthy, given the region’s attempts to create a more sustainable economy in the wake of a major coal bust half a century ago.

My interest in energy transitions stems from my own curiosity about the fate of Wyoming’s Powder River Basin, a place that has been the United States’ largest producer of coal for 30 years. I grew up there in a town called Gillette and later returned as an anthropologist to study gender, kinship, and labor in the mines where I worked. Whereas my original work and research took place during a period of expansion from 2000–2008, by 2021 the region had experienced what appeared to be a severe downturn. In March 2016, more than 500 full-time coal miners were laid off in one day. In the summer of 2019, two of the region’s dozen mines locked their gates when their operator abruptly declared bankruptcy. The downturn was covered in the national news, including by The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, and CNN.

I arrived in Gillette in June expecting to find the protracted bust dominating everyday life and conversation. I did not.

I drove past bright LED billboards advertising full-time mine production jobs. I found thriving local businesses and full restaurants. I found a booming housing market due to a suspected “Zoom boom” of people choosing to live in Gillette while working remotely for companies elsewhere. I found that the high school girls softball team had just been crowned state champions, winning their title at the newly expanded multimillion-dollar Energy Capital Sports Complex. (Gillette, like the rest of Wyoming, may be a Republican stronghold, but elected officials there have a strong record of investing significant public funds in community infrastructure, especially for kids.) I found fewer former President Donald Trump flags and T-shirts per capita than in the “liberal” town where I live in Colorado, despite the mainstream equation of coal country with Trump Country.

While many of the people I spoke with in Gillette were optimistic about the possibility of the coal market rebounding, the materiality of the coal itself largely precludes the kind of resuscitation happening in places such as southern Colorado. The Powder River Basin coal is thermal, not metallurgical, meaning that it is burned almost exclusively to generate energy and is therefore less tenable in a carbon-constrained world.

The signs of decline—and pessimism about the future—were most evident in the mine equipment itself, not in public discourse. When I toured the mines around Gillette, the material things painted a fraught picture of the coal industry’s past, present, and future.

Viewing the idle equipment at one mine, my seasoned eye noted that the giant tires were full of markings that signaled damage. Technicians watched these areas carefully, as tire damage can quickly become lethal for the operators whose cabs perch on top of them. The tread also looked worn thin, suggesting that the tires had not been replaced because the equipment was not expected to have a long future productive life.

At another mine, workers told me that rather than fix haul trucks, they had to “cannibalize” them, or use them to harvest parts to make other ailing trucks functional. The term “cannibalize” underscored that for the miners, trucks were not just objects.

Read more on coal’s consequences, from the archive: “The Struggle to Protect a Tree at the Heart of Hopi Culture.”

As I’d found in my previous research, miners frequently gave human names to the equipment and spoke about them as if they had human qualities and agency. The equipment provided the conditions of safety for miners and mediated the majority of human interactions. Miners assessed the company’s care for them as people by how well they were allowed to treat the equipment. The cannibalized trucks and worn tires indexed a company’s short-term investment in a mine’s future and lack of care for workers.

Curious about other regions that had weathered coal market collapses, I next visited the southern Colorado coalfields. Twenty miles north of the resuscitated New Elk Mine lies Ludlow, a site whose current neglected condition belies its crucial role in U.S. labor history.

From 1913 to 1914, headlines from the Colorado Coalfield War gripped readers across the United States. Around 10,000 miners across the region had been striking against John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s Colorado Fuel and Iron Company (CF&I), citing low wages and the deadliest working conditions in the country. Miners who made trouble were evicted from their company-owned housing in the company towns where they lived, leaving them and their families to shelter in tent colonies organized by the UMWA.

On April 20, 1914, soldiers from the Colorado National Guard and CF&I private security forces attacked the Ludlow tent colony, leaving roughly 20 dead, including two women and 11 children. The attack immediately became a potent symbol of corporate malevolence, eclipsing the ensuing “Ten Day War” in which miners retaliated by killing at least 30 men and destroying six mines and two company towns.

Ludlow was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2009. Mining had largely stopped half a century earlier, as industry turned to oil and gas, and the steel mills in nearby Pueblo replaced their coal-fired furnaces and coke ovens with electric systems. The UMWA erected a memorial in 1918 that suffered vandalism in 2003. A repaired monument was unveiled in 2005, along with what appeared in August to be a security camera. The site stands a lonely mile west of Interstate 25, enclosed by a fence whose gate swings open along with wind gusts.

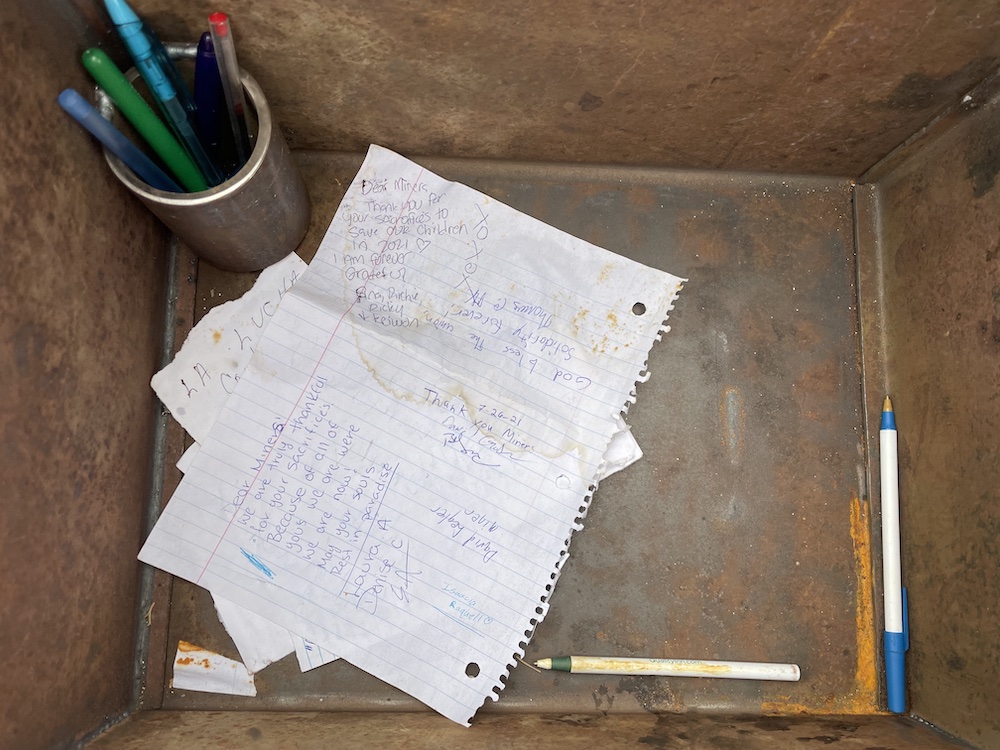

The posts closest to the gravel parking lot were covered with stickers, many from union chapters from across the state and country. During my visit, I found a metal box holding a cup of pens and a few hastily torn out pieces of notebook paper with statements of appreciation for miners. Flowers, flags, and coins had been laid at the base of the memorial. Multiple signs offered the UMWA interpretation of the massacre site. Adjacent to the memorial was a covered picnic area and a locked off area that appeared to have once been a stage or stand. Paint was peeling off the benches and picnic tables, hinting at a lack of official upkeep.

About a mile south, the ruins of the Ludlow Depot had collapsed in on themselves, with no apparent fanfare. I was touched by the sincerity of the few offerings that were there but grieved, listening to vehicles buzz by on the interstate, completely unaware that they had just passed one of the most significant sites of U.S. labor and energy history without so much as tapping their brakes.

The neglected state of the Ludlow monument reinforced my worries about the future of mining towns such as Gillette, including how they will be remembered (or forgotten) as the U.S. phases out coal-fired electricity.

During my 2021 return trip to Wyoming, I also visited the closest thing the town has to a monument to the coal industry: an equipment graveyard that doubles as a public park. I discovered birds living inside of the retired 170-ton mine truck on display. They chirped happily as the breeze silently turned the fan at the truck’s rear, a stark contrast from the decibel levels that would have been present when the truck was operational.

They were the second set of birds I had witnessed making a home inside of idle mine equipment that day—the first had been living inside of the idle haul trucks with worn tires I witnessed at the mine itself.

Perhaps the birds’ chirping is a reminder of the life that still animates both Gillette and the coal industry.

How might we interpret the birds who have made homes inside the idle Wyoming mine equipment? The most famous mining birds, of course, are the canaries doomed to serve as warning signs of a poisonous underground workspace. Perhaps these Wyoming birds are warnings of continued cannibalized trucks, job losses, and dwindling public coffers.

Perhaps they remind us of the challenging environmental reclamation needed to return the mined areas to sagebrush grassland. Each of the mines has filed a reclamation plan and is bonded with the state, but if a mine is abandoned, the costs of reclamation could exceed a company’s assets and leave the State of Wyoming to foot the bill. This possible future seemed immanent when the two mines closed their gates in 2019, after having been bought and sold to progressively less financially solvent companies.

This practice is not limited to Gillette. The UMWA miners in Alabama who were striking that same summer of 2021 were criticizing a similar practice: They had lost their jobs when the mine’s first operator went bankrupt and then were rehired by the purchasing company, but without benefits and US$6 an hour less for wages. Selling off debts to the next bidder is a pattern that is already well-established—and critiqued—in the problem of “orphan wells” in the oil and gas industry.

But perhaps the birds’ chirping is also a reminder of the life that still animates both Gillette and the coal industry.

The graffiti in the equipment graveyard could be interpreted as evidence of neglect, with fewer public employees to maintain and clean the machines. It could be interpreted as evidence of a more disillusioned take on the industry’s role in town and corporate accountability to the publics that supported it.

But it could also be interpreted as evidence that the industry and its people are not yet ready to be treated as history for others to view—or to ignore. Not yet ready to become another disregarded memorial, such as the Ludlow monument 530 miles due south that energy consumers speed past on their way to be somewhere else. Just transitions are predicated on remembering coal communities’ contributions to our everyday lives.

This article has been edited slightly from the original for style and clarity.