How Fracking’s Appetite for Sand Is Devouring Rural Communities

How Fracking’s Appetite for Sand Is Devouring Rural Communities

“Do you want to see the mine?” asks Harlan. [1] [1] Pseudonyms have been used to protect the identities of people interviewed in Dovre over the course of the author’s research.

“Of course,” I reply.

He fetches his boots. We head outside with his wife Edith and follow a row of fledgling soybeans as we stroll across a few acres of farmland.

It’s June 2014, and I’m in Dovre, a rural community in western Wisconsin where farm fields hug tree-covered hills and cattle graze lazily in the afternoon sun. A wooden 19th-century Lutheran church sits at the center of town, along with a one-room town hall.

Harlan and Edith spent most of their lives as dairy farmers in this once tight-knit community, just the two of them and around 40 cows. As we walk, they reminisce proudly about a life rooted in hard work and strong communal ties. Their view of community includes neighbors, but also something more, a commitment to reciprocity that entails a give-and-take between people, animals, and the land.

“We took care of the cows,” says Harlan, “and the cows took care of us.”

They speak fondly about the lifetime of labor they invested in their farm, putting up the barn, the silos, the shed, the milk house. They talk about maintaining the soil and managing the woods. Each hill, each of the surrounding farms, has its own story.

But now sand mines are erasing those stories—“putting the land blank,” as Harlan says.

Nearing retirement in the early 2000s, Harlan and Edith sold much of their property to another farmer and then built a house on a hill nearby, where they could look out at the land they passed on to its next steward. For people like Harlan and Edith, you don’t actually own land. You just care for it until you move on, a cycle they assumed would continue. Several years into their retirement, however, the other farmer sold the land to an out-of-state mining company and then left town.

We reach the end of the field and push through some brush, emerging at the edge of the mine—a 20-foot drop into a flat moonscape that covers about 120 acres, half of it curving around a hill and out of view. Harlan looks grief-stricken as he stares intently into the massive pit containing a unique treasure: pure silica sand. An excavator scoops loads of it into a dump truck.

The land erased. A community frayed.

“Well, let’s put it this way,” explains Harlan. “Everybody that I know around here that sold to the companies moved out, so that should tell you something. And right now, we’re surrounded, and it just makes you feel like they’re squeezing you too.”

The mining company has visited Harlan and Edith several times, but they prefer to hold out. “They keep coming over,” says Edith, “and we’d both like to see it farmland. But how long can we hang on?”

Phrases such as “being squeezed” and “hanging on” allow Harlan and Edith to express a type of loss, even trauma, that is both individual and collective. They watch mining transform the landscape and feel alienated from a place that had once anchored their sense of belonging. They are not alone.

Over the past decade, the push to expand fossil fuel production in the United States through techniques such as hydraulic fracturing (commonly known as “fracking”) has reverberated far beyond oil rigs, pipeline routes, and petrochemical complexes, pulsating unexpectedly through communities like Dovre.

Fracking involves drilling deep into underground rock formations to release natural gas or oil. And it uses sand. Lots of it. Sand props open tiny fissures in the bedrock that are created during the fracking process, but not just any sand will do the trick. Highly pure silica sand is especially strong and resists being crushed thousands of feet below the surface. Round sand grains of consistent size allow hydrocarbons to flow more efficiently through the well.

During fracking, just one well can require several thousand tons of sand. To put that into perspective, industry forecasters predict that more than 100,000 new wells will be drilled over the next several years in Texas’ Permian Basin alone. But fracking is not limited to Texas. The last decade has also seen drilling booms in Pennsylvania, North Dakota, Wyoming, and Alberta, Canada, among other places. Last year nearly 70 million tons of sand was mined in the United States for fracking.

It just so happens that Wisconsin is uniquely positioned to supply fracking rigs in North America with some of the best sand available. Deposits of silica sand that formed some 500 million years ago are concentrated in western Wisconsin. While sand mining also occurs in Texas, Arizona, and Oklahoma, among other states, Wisconsin’s sand is especially prized for its strength and purity. It’s also close to the surface, so digging it up is relatively easy. And profitable.

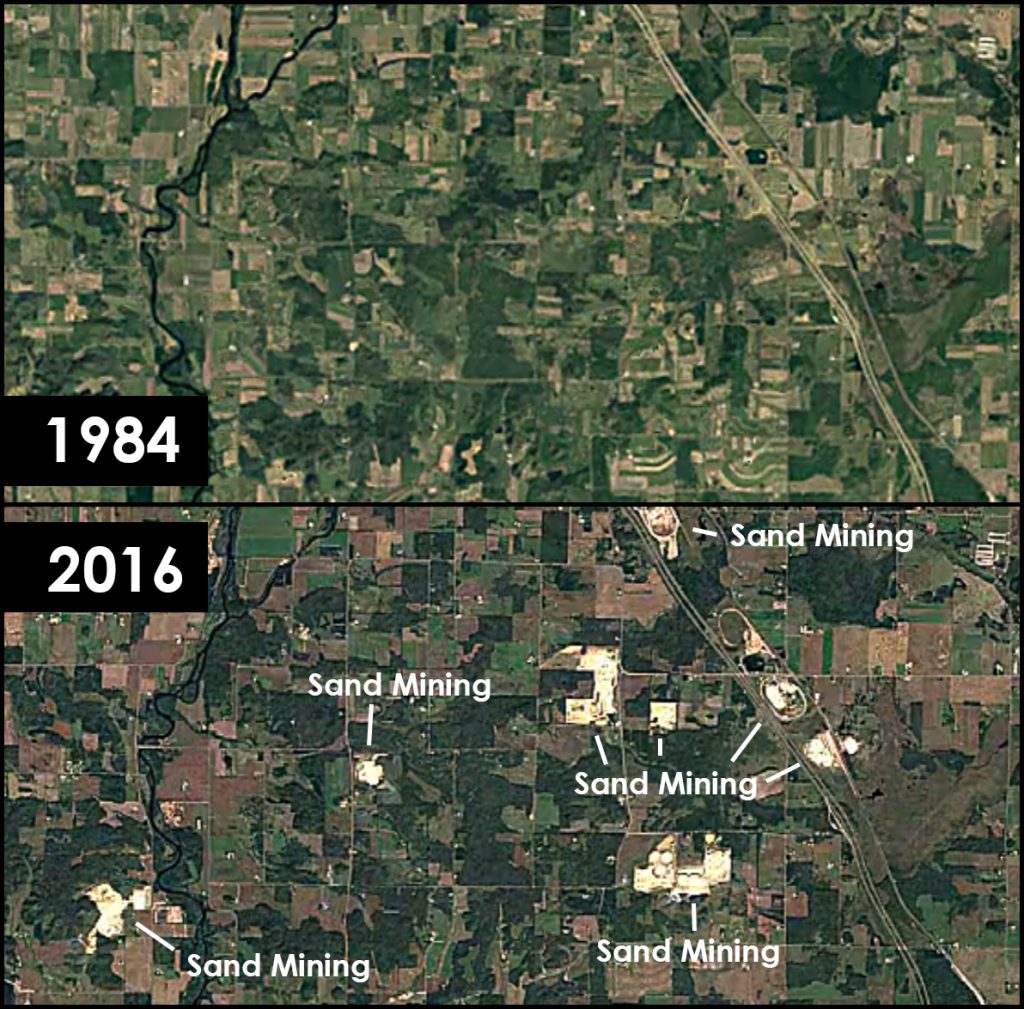

Since the mid-2000s, the growth of fracking has powered a booming frac sand mining industry in western Wisconsin, with hundreds of operations cropping up across the countryside. Some people clearly benefit. Lucky landowners may see a windfall in selling or leasing to a mining company, and others may find work at mining operations or by driving trucks. Down the line, consumers enjoy cheap fuel. But at what cost?

Frac sand mining disturbs once-quiet rural towns with blasting, truck traffic, and industrial activity. It generates new environmental health risks, and some residents worry they are being exposed to microscopic particles of airborne silica dust that cause silicosis, an often fatal lung disease. Mining also flattens hills and alters scenic bluffs, disrupting not only a picturesque rural landscape but places that are deeply meaningful to people. Perhaps most significantly, the mining boom in communities like Dovre has fomented division and distrust as residents grapple with a resource boom that brings both wealth and ruin.

As the geographer Gavin Bridge writes, “One person’s discovery is another’s dispossession.”

Dispossessing people of resources or land is one thing, but the disruption caused by mining is commonly expressed as a form of assault—a kind of violence not only against the land but also people’s relationship to it. Residents often struggle to convey their emotions, drawing on images of invasion, illness, and violence, describing the hills as “cut open,” “disfigured,” or “scarred” by mining.

“No one invited the pillaging hordes of Genghis Khan either,” stated one resident in a letter to a local newspaper as she compared out-of-state mining companies to an occupying army. “Let’s prevent the cancer,” wrote another man, relating mining development to the metastatic spread of a life-threatening disease. “When they mine this, they rape this land,” a man told me, his gaze as empty as the pit being dug across the street from his home. “I don’t know any other word to use but ‘rape.’”

It’s not just retired farmers like Harlan and Edith who grapple with this kind of dispossession. Joe and Nancy moved to rural Wisconsin after living their entire lives in a large Midwestern city. The countryside represented a sanctuary from the grind of city life. Several years after they resettled, however, a neighbor sold a parcel of his land to a mining company. When the mining started, says Joe, it was like getting “smacked in the head with a two-by-four.” In addition to noise and dust, the pain was psychological, he remembers.

“The first year they were here,” Joe explains, “I’d go out and walk the dog in the morning … then I’d go sit in the basement. I felt like I was in solitary confinement, in jail. I mean, I gained weight anyhow [after retirement], but I gained a hell of a lot more weight then. I didn’t want to go outside. I was sick. Your life is just turned upside down.”

Lisa’s life has similarly been upended. Several years ago, two frac sand mines opened within a mile of her home and the barn where she boards several horses. Trucks drive by all day long. A processing plant runs nonstop, loading railcars by the thousands. She constantly deals with noise, vibration, and interrupted sleep, and she worries about possible exposure to silica dust.

“I’m told I’m exaggerating when I talk about the sheer dust that’s in this house. In the middle of summer, I can start [dusting] on this end,” she says, pointing to one side of her kitchen, “and by the time I get to this end, there’s a layer of dust on that countertop.”

She has complained to local officials, but as she sees it, they support the mining industry and have downplayed her concerns. “I’m told that I’m lying, that I’m ridiculous, I’m exaggerating, I’m crazy.”

Uncertainty about the nature of the dust is a source of continual anxiety. She feels unsafe in her own home and abandoned by elected officials who she thought were supposed to watch out for her well-being.

To truly grasp her experience, it is important to recognize that people in the United States associate certain meanings with the idea of home: order, security, investment in the future. Mining may disrupt these expectations, leaving people feeling extremely vulnerable, if not hopeless.

It makes sense that some residents would prefer to live elsewhere. But leaving one’s home also brings with it complex feelings of loss.

Heidi says she felt “empty” when she sold her 19th-century farmhouse after multiple mining operations were permitted to operate nearby. The mining company bought her out so that they wouldn’t have to deal with a frustrated, outspoken resident living next door. She accepted the buyout, her one chance to “escape,” as she puts it. Others were “not so lucky,” she says, and she struggles with the guilt of leaving friends and neighbors behind.

While she elected to sell her home to a mining company, it was a choice constrained by circumstance. Her only other option, she says, would have been “to grow old and be some pissy old woman sitting in the middle of the driveway yelling at all the trucks going by. I would’ve lost everything.”

“It was very traumatizing,” explains Heidi, “to feel pushed out of our home.”

The sense of loss expressed by some people in Dovre extends beyond feelings of vulnerability or the trauma of relocation. Like Harlan and Edith, some lose connections to places that were once immensely meaningful—that were part of them.

Marleen has lived in Dovre for over 80 years. Historical photos of her farm, which her grandfather purchased in the 1890s, hang prominently in her living room. When hosting visitors, she likes to thumb through photo albums and tell stories about family and friends. Her husband was laid to rest in the cemetery next to the Lutheran church.

For Marleen, memories are etched into the rural landscape, a genealogy of kin ties linking past to present. These ties transcend her own property. Her grandfather, for instance, worked on a different farm up the road when he first arrived from Norway—one that is now being mined for sand. In fact, it is the same land that Harlan and Edith once owned.

“And I [had] always felt good about that,” Marleen says mournfully, “that I could go up there, and I was actually stepping on soil where my grandfather lived.”

Now the hills are gone, replaced by “pyramids of sand,” she scoffs. These are the stockpiles at a nearby processing plant being readied for shipment to the drilling rigs.

The land has been put blank.

“It’s sickening, just sickening,” says Marleen. “I wish it was like a dream, and you wake up and it was a dream and it didn’t happen.”

Editors’ note: People and places described in this essay are further discussed in the author’s book, When the Hills Are Gone: Frac Sand Mining and the Struggle for Community, and his article in the journal Human Organization.