The Symbolic Power of Virus Testing

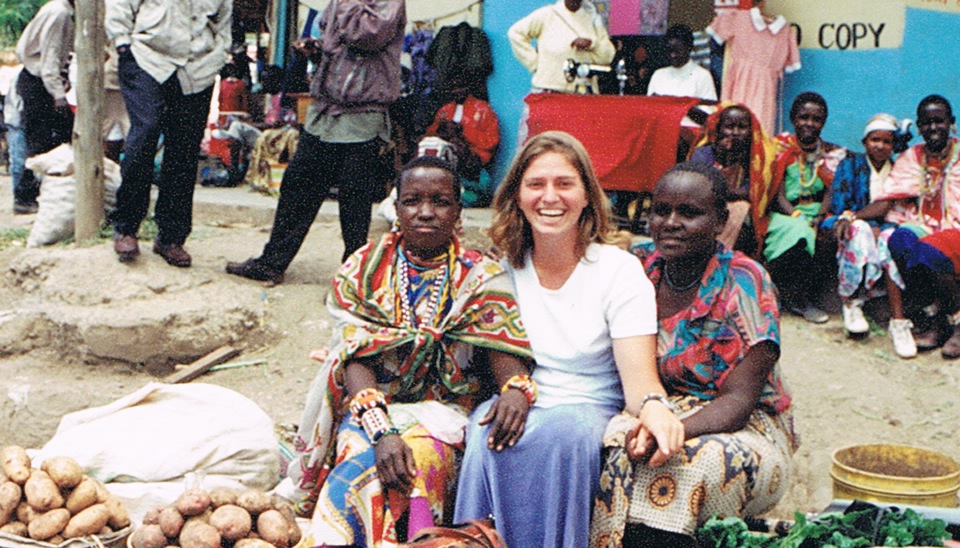

In 2000, as a newly sworn-in Peace Corps volunteer in Kenya, I headed off to my field site among the Maasai after completing training in public health focused on HIV education. I arrived in Narok, Kenya, which was to become my home for the next two years. Little did I know, it would become my lifetime second home.

I spent the first few months settling in and getting to know community members. Inevitably, people would ask why I was there, and I would try to explain in my then-limited Kiswahili that I was a public health volunteer tasked with assisting in the HIV/AIDS response. Over and over again, I was met with laughter and “hakuna ukimwi hapa,” which means, “no AIDS here.” People would go on to tell me that they knew about HIV. The disease was only in the big cities—not something to worry about in Maasailand.

Such a response is common. It is hard to imagine the gravity and danger of something you cannot “see,” as anthropologist Hugh Gusterson recently wrote. As a result, when a new virus emerges, people rely on preexisting explanations—and biases—for the illness, particularly as they react with fear and blame. In the 1980s, HIV was considered a “gay plague.” During the swine flu pandemic, Mexicans and other Latinos became the scapegoats. In 2014, some portrayed the Ebola outbreak as being from the “dark continent.” Similarly, as the first cases of COVID were confirmed in Wuhan, China, early racist stereotypes took root through the use of the term “Chinese virus.”

But no matter how far away and unimaginable the threat first seemed, it was quickly proven again that infectious viruses do not discriminate. On January 21, the first COVID-19 case was confirmed in the United States. Since that time, the country has become the epicenter of the pandemic: As of this writing, the United States has had 1,005,147 confirmed cases and 57,505 reported deaths. Yet, despite such dire numbers, some people want to believe the virus is “just like the flu,” while others still believe the pandemic to be a “hoax” and defiant protests against stay-at-home orders have occurred nationwide. Kentucky recently reported the highest infection increase one week after protests.

These patterns illustrate that when people cannot “see” a danger, they fill the void with their own theories and interpretations, which can have a direct impact on needed interventions. It is easier for people to comply with orders and recommendations if the threat of the virus is more tangible. That is what community-wide testing can offer.

During my time in Kenya in the early 2000s, I facilitated community HIV awareness discussions focusing on an invisible virus. At that time, the HIV prevalence in Kenya was 14.1 percent, and only around 5 percent of HIV-positive people had access to antiretroviral drugs due to their high cost. While Kenyans could not “see” HIV, it was indeed present and still a risk that needed to be addressed.

During my three years as a Peace Corps volunteer, two key things led to the community’s change in perspective about the virus. First, as HIV prevalence spread, more people became sick and died. The disease made itself visible as family, friends, and loved ones slowly succumbed to the virus or a compromised life. The devastation where there was no available treatment left little doubt that HIV had found its way to rural Maasai communities and that it was not just a threat confined to cities.

Also, in 2003, I—along with a small coalition of community members—launched the first HIV voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) center in the Narok District, southwest of Nairobi, called Narok Pillar of Hope. During the planning stages, we were repeatedly told that no one would come to the testing facility because of the stigma associated with HIV. These critics were proven wrong.

By the end of our second year, we had tested over 2,000 people for HIV. As one of the VCT counselors, I was inspired by the conversations I had with clients during pre-counseling, rapid testing, and post-counseling. What impressed me the most was how committed people became to changing their behaviors once they received their test results—whether positive or negative. Post-test counseling consisted of individualized plans for reducing risk, such as limiting sexual partners and using condoms.

It was striking how much symbolic power a simple test kit—a physical object displaying the presence or absence of an invisible virus—could possess. HIV testing did more than track a virus: It gave clients agency over their lives and decisions.

Due to this global pandemic, many of us sit confined to our homes, physically distanced and hoping for the best. We desperately need agency over our lives and decisions. This novel coronavirus is, like other viruses, an invisible threat—one that is similar to HIV in that people with no symptoms can carry and spread it.

There is a paradox in the narrative for understanding this virus. The physical distance necessary for decreasing the transmission rate leaves people isolated from others, keeping the virus invisible to most people. Health care workers who face the virus daily, and the ramifications to their families, have no doubts about this threat’s validity.

For those who do not “see” the virus, the pandemic can only be left to the imagination, fed by preexisting assumptions, social media, and what people read in the news. While many reporters and health care providers are working to make the virus more tangible to those of us on our couches, there is still more that needs to be done.

As the world continues debating the right strategies for reopening countries, one strategy that everyone can agree on is the need for testing. From an epidemiological perspective, community-wide testing is the linchpin in mitigation efforts to flatten the curve of new infections. It is essential to identify and track each case in order to successfully isolate the virus and protect others from getting sick.

But I see an additional benefit to community-wide testing. Just as I experienced with HIV testing in Kenya in the early 2000s, testing itself brings symbolic power to a physical object that can transform the threat of a virus from being unseen to becoming seen. Test results can give people agency over their lives, rewrite narratives of an illness, and reinforce behavioral changes. Increased personal agency may be the key to solidarity and a united global effort to overcome the coronavirus crisis.