When Marine Mammals Clash With Archaeological Heritage

Off the southern California coast lies a small, windswept, and perpetually fog-covered island, often overlooked by visitors in favor of sunnier cousins to the east like Santa Cruz Island. The few tourists who arrive here on San Miguel Island must come by boat, navigate a skiff through the surf, and endure an exhausting, often slick, vertigo-inducing hike along a steep canyon ridge to the Channel Islands National Park ranger station. And that’s just the warmup.

From here, the most ambitious opt for a guided, trans-island, 16-mile round-trip adventure out to the far western side of the island, Point Bennett. The day-long hike requires that you leave with the rising sun. You begin with a climb to the top of the highest peak, San Miguel Hill, at 831 feet above sea level. A quick detour takes you to an overlook of a “caliche forest”: a ghostly assemblage of the white, twisted stalks of trees that died more than 10,000 years ago, preserved by blowing sands, rainwater, and dissolved seashell that turns to limestone-like geological formations. It is a dramatic illustration of how things have changed on this island over time.

The remaining hike takes you past the scattered debris of a World War II plane crash to the edge of a 300-foot-high bluff overlooking the far western edge of California. As you crest the last small rise before arriving at Point Bennett, a symphony of barking and babbling sea mammals welcomes you. The beaches below teem with the greatest diversity of pinnipeds (seals and sea lions) found anywhere in the world, including furry and stocky northern fur seals, lounging northern elephant seals, skittish harbor seals, barking California sea lions, and relatively rare Guadalupe fur seals and Steller sea lions. It’s a sight unlike any other.

San Miguel and the seven other Channel Islands are often viewed as time capsules: carefully protected natural remnants of an idyllic time in California’s history before the arrival of Spanish missions, miners, and fortune seekers. In many ways, this is true. On your next trip to San Miguel, you are likely to see brown pelicans flying in formation over azure and turquoise waters, brilliant pops of yellow from tree sunflowers, and curious looks from cat-sized island foxes. It is easy to lose yourself in the natural beauty.

If you look more closely, however—as archaeologists like me tend to do—you will see evidence of a long history of human influence here, with a Native American history stretching back at least 13,000 years. Nineteenth- and early 20th-century fur hunters drove sea otters, seals, and sea lions to the brink of extinction; Euro-American ranchers decimated the vegetation communities for over a century. It is only in the last 50 years or so that protection of the island has allowed all this natural beauty to become reestablished.

Ironically, the archaeological evidence of what this place used to be like is now being wiped away by the very same marine mammals protected in this island park. They are literally—without malice or blame—stomping on the historical record of this precious place. As sea mammals and other natural resources bounce back, cultural resources are, sadly, being washed out to sea.

I have worked on San Miguel for most of my professional career. My first research expedition was nearly 20 years ago, as a young archaeology graduate student at the University of Oregon. Our mission was to evaluate dozens of archaeological sites and report back to park service managers the ways erosion has been impacting sites. Our work found us scrambling up slick dune faces, dancing along sea cliffs, twisting and turning through giant fields of iconic yellow coreopsis flowers, and covering over 10 miles of uneven, thickly vegetated terrain each day. It was exhausting, and exhilarating.

Hundreds of archaeological sites have been recorded on this small island in nearly every corner and imaginable setting: in caves and rockshelters, atop mountains and sand dunes, and along beaches and rocky shores. These archaeological sites attest to the deep history of the Chumash Indians and their ancestors, who continuously occupied the Northern Channel Islands for at least 13,000 years, until the trauma and chaos of Spanish contact and settlement starting in the 1500s resulted in the abandonment of the islands and relocation to mainland towns and villages by the 1820s.

In the mid-19th and early 20th centuries, thousands of sheep and other livestock were kept on San Miguel by Euro-American ranchers: the hike up to the ranger station leads past the scattered remnants of one of their ranch houses. Invasive plants and animals were introduced during this period, and overgrazing resulted in the near complete de-vegetation of the island. San Miguel was a sandscape, a post-apocalyptic wasteland. When my Ph.D. advisor first arrived on San Miguel in the 1980s, he was told to take care not to step on any of the straggling plants on the western part of the island.

The island was made a national park in 1980, and management and island recovery have been spectacular. Park managers have removed or eradicated many invasive plants and animals, planted native vegetation, and provided monitoring and protection for the island’s unique native flora and fauna. Today it’s difficult to see the handprint of humanity here. One of the rare, amusing signs of people can be found near the skiff landing at Cuyler Harbor: four out-of-place palm trees, likely planted during filming of the 1935 Academy Award Best Picture winner Mutiny on the Bounty, with Clark Gable.

Change has been even more dramatic for the marine mammals.

I have been lucky enough to work in the Point Bennett area for years. Even for archaeologists, this is a rare treat. As one of the world’s most sensitive breeding and haulout locations for six federally protected sea mammals, access is limited to the marine mammal biologists who study and monitor these animals throughout the year. Every time I visit the point (once every few years), NOAA biologist Robert DeLong has kindly acted as our escort, historian, and colleague on research adventures. DeLong is a San Miguel Island legend, having worked at Point Bennett for over 50 years. No one has more direct experience and is more knowledgeable about the history and recovery of the San Miguel Island pinniped communities.

Along Point Bennett, we have documented, dated, and sampled dozens of archaeological sites that span the last 10,000 years, uncovering tens of thousands of sea mammal bones and revealing that the earliest settlers here had access to—and hunted—sea otters, seals, and sea lions. Human hunters consumed these animals’ meat, fashioned tools with their bones, and, likely, used their pelts and blubber for warmth.

In nearly the dead-center of the Point Bennett landmass rests the archaeological remains of a massive Chumash village bountiful with broken and discarded projectile points and scattered fish and sea mammal bones.

Any pinniped that ventured onto the local beaches while the Chumash occupied this thriving village would have met an unfortunate and speedy demise; they probably instead stayed on offshore rocks and tiny islands to avoid hunters. For now, no one knows how many marine mammals thrived here at that time, but there’s no evidence that the Chumash hunters had a major impact on their population numbers.

Every year, every month, and every day more material is lost.

With European settlement, the pressure catastrophically increased. Nineteenth-century commercial sealers relentlessly hunted sea otters, seals, and sea lions for their pelts, blubber, and trimmings (penis and testes for the Asian medicinal market). Just a century ago, these animals were nearly wiped off the planet and widely believed to be extinct. DeLong describes his early years working on the island in the 1970s with only a few thousand pinnipeds.

A dramatic recovery followed the passage of the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972. While otters remain largely absent from Channel Island waters, the populations of other sea mammals have boomed. Today Point Bennett is so overcrowded that juvenile and subadult males are forced to relocate to beaches as far east as Santa Rosa Island (more than 10 miles away), awaiting their turn to overthrow dominant males and take charge of their harem of mates. These marine mammals now occupy beaches and landforms that have been unavailable to them since the first Native Americans arrived.

Today overcrowding of pinniped communities along San Miguel beaches has created an archaeological crisis. These animals are hauling out of the water onto cultural heritage sites, defecating on them, and impacting them in dramatic ways, including causing erosion that washes artifacts away.

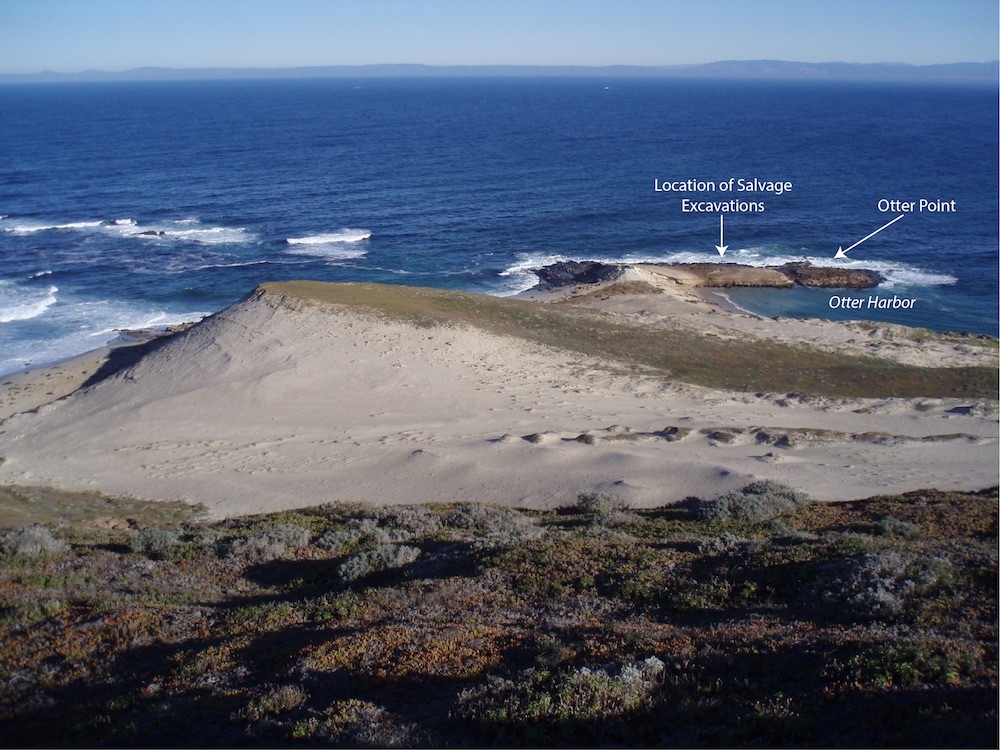

Ten years ago, DeLong, a number of archaeologist colleagues, and I documented the impacts of a new breeding community of California sea lions on northwestern San Miguel at a place called Otter Point. We estimated that the erosion created by these massive animals sitting atop a 1,200-year-old Chumash village led to the washing out to sea of over 52 cubic meters of archaeological materials, including some 1,700 artifacts (for example, stone projectile points, shell fishhooks, and shell and bone beads and ornaments)—all in just 12 months.

Channel Island National Park managers are working hard to address the problem, but their options are limited. These animals are federally protected and need places to breed and escape human and predator intrusion. Marine mammal biologists must be able to monitor populations as they contend with disease, food shortages, and other impacts to their health and recovery. Our national park system was designed, in part, to help with these kinds of challenges. Managers have tried to build fences to keep marine mammals out of specific areas of the central California mainland coast, but this strategy doesn’t work: The animals simply plough right through them.

The only option, really, is to fund archaeological documentation and salvage projects to save as much information as we can before it is lost forever. My colleagues and I recently secured a small grant to revisit, map, and sample several heavily impacted sites at Point Bennett. Our work is set to begin late this summer, but this is just a drop in the bucket. More work is sorely needed, and quickly. We need resources to map eroding sites, collect radiocarbon samples, and excavate the remaining intact deposits from sites that we know little or nothing about. Every year, every month, and every day more material is lost.

These sites are not just an excellent record of ancient human history in southern California. Archaeological sites are the ecological archive of what the world looked like prior to globalization, industrialization, and the impacts of modern human activities that have so fundamentally altered our planet. They are critical to help build sustainable recovery and management plans into the future.

For example, sea mammal bones recovered from San Miguel Island archaeological sites tend to be from either sea otters or Guadalupe fur seals. Today no otters are found along San Miguel waters and Guadalupe fur seals are rare visitors. Something has fundamentally changed. The distributions of these animals in the 10,000 years prior to historical overhunting by fur traders may have been very different from their distributions today. Without knowledge of what the world looked like before dramatic human impacts, how can we decide on a path forward?

We still have many questions to answer and much management to realize. But time is running out: The patients are destroying the evidence we need to formulate a cure.