Remembering the Forgotten Chinese Railroad Workers

In 1864, 15-year-old Hung Lai Wah and his older brother Hung Jick Wah laid an offering at the Hung family temple in Dailong Village, Guangdong, China. They were about to cross the Pacific Ocean to raise their family’s fortunes by working on a U.S. railroad. They would labor 12 hours a day, six days a week, preparing the ground for the tracks to follow and blasting through the solid granite bedrock of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, happy if they advanced 6 inches a day. Hung Lai Wah would become the boss of a work gang of 30 men. Hung Jick Wah would lose an eye to the endeavor. Many others would lose their lives.

As the two brothers burned incense and bowed before the altar of their ancestors, they had no way of knowing that it would be over 150 years before a descendant of theirs, Russell Low, retraced their steps on the American railroad.

I met Low, a physician from California in his mid-60s, as the sun rose over Salt Lake City. It was a cold morning in early May 2019. As we drove north around the Great Salt Lake, the weak light strengthened, illuminating snow-capped mountain peaks until, hours later, we turned onto a Bureau of Land Management backcountry byway.

It was the first day of the Chinese Railroad Workers Descendants Association conference in Utah, put on to mark the 150th anniversary of the completion of the first transcontinental railroad. In 1869, the ceremonial “golden spike” was driven in at Promontory Summit, Utah, which is near where we gathered. More than 400 people came to the conference to honor the lives of the estimated 10,000 to 15,000 Chinese men who were instrumental in the massive, dangerous project. Some, like Low, could trace their genealogical roots to individual railroad workers. Many could not, but they still strove to learn. As the Chinese proverb, or chéngyŭ, goes: “When drinking water, remember the person who dug the well” (吃水不忘挖井人; chī shuǐ bù wàng wā jǐng rén).

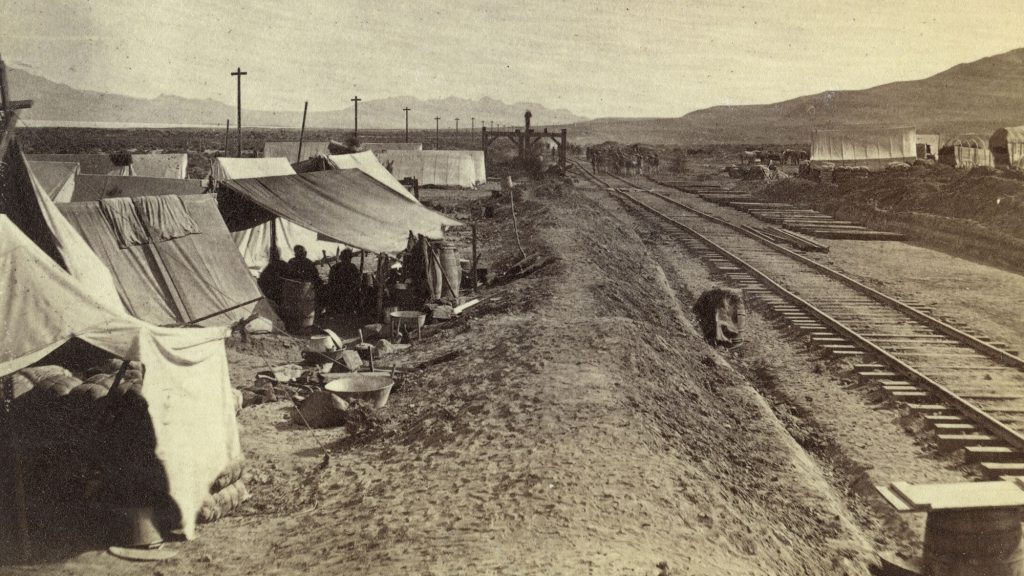

The transcontinental railway was primarily built in two extensive portions by two corporations. Union Pacific Railroad, which built the section east of Salt Lake City, mainly relied on Irish and other European immigrants for their labor pool. Central Pacific Railroad, which built the western segment, had to compete with lucrative mines for laborers; they instead relied on Chinese workers, many of whom were fleeing the aftermath of the opium wars and the Taiping rebellion back home. They were paid less and worked longer hours than their Euro-American counterparts.

Despite the huge presence of these Chinese workers, few Chinese individuals were named in the payroll ledgers and other historical documents of the late 1800s. Racial prejudice by Euro-Americans tended to erase or discount Chinese American contributions. Because of this, the descendant community is bound by a shared yearning to know what it was like back then. What did these workers eat? Where did they live? How did they relax?

Archaeology, the study of the material remains of the past, is uniquely positioned to explore these questions. Archaeologists have been studying Chinese railroad work sites for over 50 years and, in 2012, the archaeology network of the Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project (CRRW) began collecting and presenting their results.

As a museum registrar in the historical archaeology lab at Stanford University, where I worked for the director of the CRRW archaeology network, and as a Chinese American, I went to the Chinese Railroad Workers Descendants Association conference in May—and volunteered on a tour with 200 attendees over two days—to help show how archaeology provides one of the clearest windows into what life was like for some ancestors of the participants. But, in the end, what I witnessed was more than just a one-way history lesson.

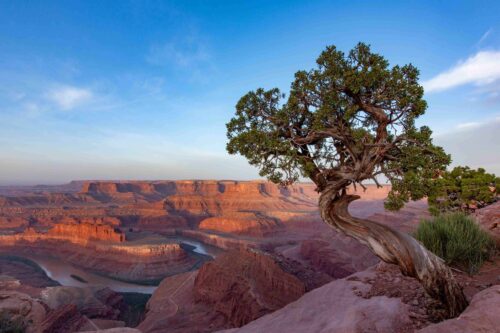

On the backcountry byway, two hours into the tour, at first it didn’t seem like we were anywhere special. Waves of sagebrush billowed in the expanse. The earth gently rose in subtle hills on either side of us. We didn’t know it, but we were already in an area where soil and rock had been removed to keep the grade at a steady level for the railway.

The radio crackled. “We are definitely going to stop here,” announced archaeologist Mike Polk, who was leading our tour. My caravan of four vans stopped at a curve in the road where, to our right, we saw a wooden trestle over a creek. Like iron flakes to a magnet, we clambered out of the vans, drawn to gaze up at the objects put in place by ancestors’ hands. We spread out, exploring the dry creek bed and embankments.

What did these workers eat? Where did they live? How did they relax?

Low walked away from the crowd. As he told me the next day, he had come to see what it was like for the young man who left everything he had known and who found himself, at one point, right where the trestle now rested. Starting with a 1903 family picture he discovered in his great-uncle’s belongings, Low has combined meticulous historical research with recorded family interviews to trace the stories of his ancestors and share those in his book, Three Coins.

Later Low told me he had looked from the long, thin scar of the railroad grade to the open, barren landscape around him. He had put his hands on some of the 400-pound stones that formed a culvert. He was impressed, he said, by the railroad workers’ mechanical abilities. But that observation “paled in comparison to the impression of touching the stone that they touched,” he noted. “It was a very durable, material connection to these men.”

We got back into the vans and wound our way to the next stop: the former town of Terrace. This was once a town of about 1,000 people settled around a railroad maintenance station. In 1870, Terrace had Utah’s third-largest Chinatown: Chinese immigrants lived on rougher land on the other side of the tracks from the main settlement. Today there is little left to mark the spot other than the foundation of the original station and a few scattered dwellings. The town was abandoned by around 1910.

Utah state archaeologist Chris Merritt passed around fragments of rice bowls, ginger bottles, Mormon ceramics, and soy sauce containers, among many other artifacts found at the site. He talked about how they were made and where: some in China, others in Britain, and even some number of them in Utah. He told the group gathered around him, listening intently, that the presence of individual rice bowls, along with a lack of small cooking vessels, indicates that the residents were served from a communal dish. Heads nodded all around, as many of us on the tour had the very same type of bowls in our own cupboards. Inside one vessel, a plum wine jar, he pointed out the fingerprint of the 19th-century Chinese potter whose creation ended up in the remote outpost. We held the fragments in our hands and put our thumbs in the space the potter left behind.

Archaeologists have been studying Chinese railroad work camps since the 1960s, but it wasn’t until 2012 that a concerted effort began to move the field beyond simple site descriptions to more detailed analyses. Archaeologists have focused their efforts on the few large, long-term camps of major earthworks like tunnels and bridges. Summit Camp at Donner Pass in the Sierra Nevada Mountains—nearly 1,000 kilometers away from where the Utah tour took place—is one such site. Chinese railroad workers lived there from the fall of 1865 to the summer of 1868, carving tunnels through the biggest obstacle to the transcontinental railroad. They worked without stopping, even during some of the worst winters on record.

Thousands of objects and features found at Donner Pass and in other railroad work camps in California, Nevada, Utah, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, and Texas reveal the dangerous conditions railroad laborers worked in and the steps they took to care for themselves. Lacking access to traditional doctors and herbal stores, Chinese railroad workers blended European American and Chinese medicines to treat their ailments—as shown by glass medicine bottles and botanical and faunal remains. The animal and botanical evidence also reveals that workers ate a more varied diet than their Euro-American counterparts, including fresh and local ingredients whenever possible.

Stanford’s Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project (which supports the archaeology network that I am a part of) collects all such information. Surprisingly, despite a concerted search for letters or other personal, primary accounts of the project, we came up empty-handed. We know through newspaper accounts from the era that many of the workers had basic literacy and did indeed send letters home. But these letters have been lost due to the social upheavals and conflict in home villages in Guangdong in the 19th and 20th centuries, and the attacks, looting, and targeted fires Chinese American communities suffered in the mid- to late 19th century.

For Lea Anne Ng, also from California, listening to the stories the archaeologists wove around us as we stood in the former town, and seeing the tangible remains of what the Chinese residents ate, the bowls they used, and what they did to pass the time, was fascinating. “I will never forget what I have learned today,” Ng told me later.

Gerry Low Sabado says she often thinks of those who have been forgotten but who should be honored.

From her bag, Gerry Low Sabado, also from California (but no relation to Russell Low), pulled out a small thermos of hot tea. She quietly asked the archaeologists if it would be okay for her to pour some for the ancestors “to show gratitude for their efforts.”

Low Sabado’s ancestors arrived in Monterey Bay, California, in the early 1850s. Some worked on railroads in California, but most of her people fished, she said. Her family stayed in Pacific Grove, California, even after their fishing village was burned in a suspicious fire in 1906—perhaps a racially driven act of arson. Low Sabado says she often thinks of those who have been forgotten but who should be honored, whether she is leading the Walk of Remembrance (a march of solidarity to the site of the village that was burned down), visiting the Stanford Arboretum (where a team is excavating a residence of former Chinese employees), or walking along an abandoned stretch of railroad. She honors the Chinese ancestors by pouring tea and offering rice at the places where they lived and worked, in her family’s own adaptation of the amalgamated Confucian and Buddhist rites of Qingming, or Tomb Sweeping Day.

Siu G. Wong, of Albuquerque, New Mexico, overheard Sabado describing the point of the ceremony to the archaeologists. She spread the word, explaining to me later that if there were any “restless spirits who are roaming the area,” especially any who had died and were not identified or returned to China for burial, the ceremony “could provide some solace and peace.”

As the group came together, people helped Low Sabado further adapt her ceremony to their needs that day. Low Sabado had with her three teacups that had been handed down to her from grandmothers and aunts. “Pour each cup three times,” the crowd told her. A young woman came back from the vans with three oranges that she had found in the snack bags packed by volunteers the night before. Participants laid them out.

“If you would like to bow with me, let’s bow,” Low Sabado said. Bending at the waist, the group bowed three times as tea soaked into dry dirt.

At the end of the tour, before driving back to Salt Lake City, Low looked around at the dry, barren landscape. At night in early May, the temperature in this part of the country can drop 30 degrees Fahrenheit to just below freezing. As we talked about the connection we felt to the Chinese railroad workers after walking in their footsteps, he said he couldn’t help but picture Hung Lai Wah and his brother Hung Jick Wah walking through that harsh environment. “I thought about how, when these men were done with the transcontinental railroad, they had to walk through this landscape to get home, to get to their next jobs,” he told me. The railroad company made no arrangements for helping the workers return home.

Many went on to reside in San Francisco or to live in mining, logging, or agricultural settlements of the new American West. Others went to the South to run grocery stores that served African Americans. Facing violence and racial animosity in the West, others moved to the cities of the East. Along the way, they left archaeological footprints behind.

I had started the tour excited at the prospect of sharing archaeological knowledge with this community. But in joining descendants as they walked in the footsteps of their history, I was reminded that the past is not a static thing. It is remembered, relived, and reincorporated into modern traditions.