Reflecting on the Rise of the Hoteps

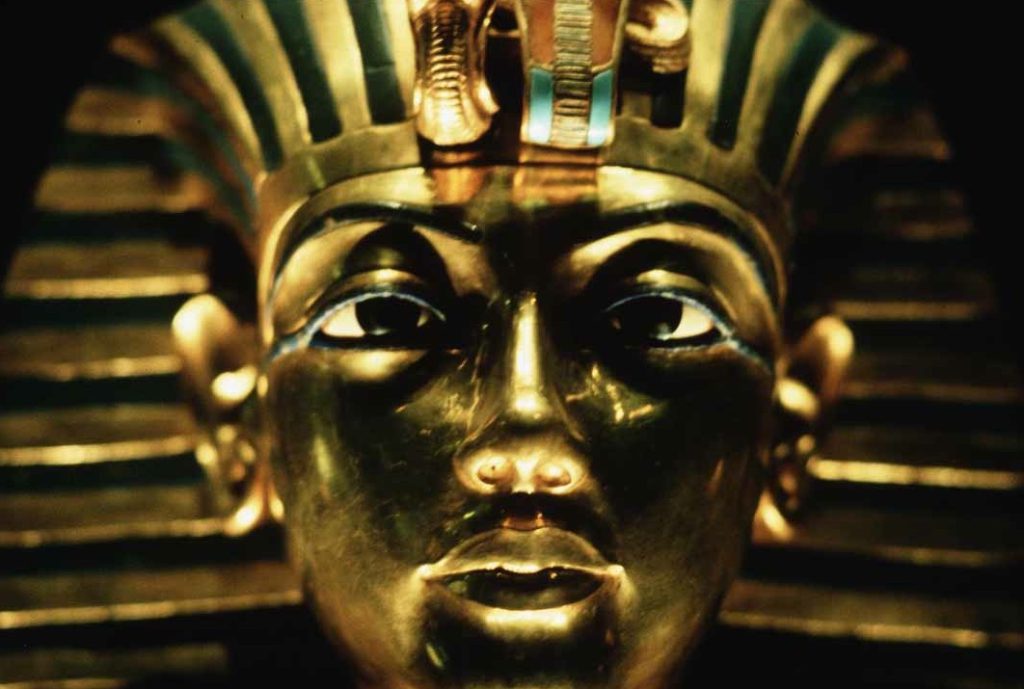

A meme circulating on social media shows “the history of a Black male” through five men: It starts with an Egyptian pharaoh, moves on to a slave, an American worker, someone with a lynching rope around his neck, and finally, an orange-suited prison inmate. The message is that Black men have fallen from grace: now imprisoned, when they once ruled.

The image falls neatly into the category of Hotep subculture: a relatively new movement in the U.S. that uses Egyptian history as a parcel to wrap up messages of Black pride. People characterized as Hoteps tend to wear traditional African styles, create content about the history of Black people from before the transatlantic slave trade, and spread ideology about the place of Black men and women within Black communities.

In the current U.S. political climate, and globally, Black pride and social justice movements such as Black Lives Matter are critical to the resolve held by those who fight against systemic racism. Not all of the ideals expressed within the Hotep movement, however, are celebratory or progressive. Hotep memes often denounce homosexuality and interracial marriage, and spread conspiracy theories or inaccurate ideas about history. They also place women as secondary to men; Hotep memes often preach that Black men should strive to fight the oppression that has disenfranchised them, but they tend to be silent about the oppression of Black women.

As a Black woman and an anthropologist interested in how cultural heritage is created, I find this subculture a fascinating case study in ideologies of Afrocentrism—where those ideas originated and how they have been adapted. It is also a lesson in what kinds of cultural pride may do more harm than good.

The term “Hotep” comes from the ancient Egyptian word for “to be at peace” and is sometimes used in contemporary Black culture as a greeting. Despite the positive connotations of the word, the term has come to be used not so lovingly; the label was put upon this microculture by outsiders to “other” those seen to have problematic beliefs and opinions. The term belongs in the same category as other microculture labels, like “hipster” for someone who is pretentiously trendy or “WASP” for someone white, privileged, Protestant, and elitist.

Pinpointing when and where this definition of “Hotep” arose is difficult. Its popularity is growing on Twitter and Instagram, as Hotep content—iconic photos, cartoons, memes—spreads these ideas.

Within Hotep memes, Black women are often presented as “Nubian queens” or “mothers of civilization” through images celebrating their beauty and power. Claims are made that they have superhuman taste and superior breast milk. They are expected to serve primarily as support to their Black husbands.

Hotep art also often conflates African imagery (picking and choosing from Africa’s 54 modern countries and countless cultures) with stereotypes of African culture, such as animal skins, “tribal” garb, and ancient Egyptian royalty. Other Hotep memes juxtapose incongruous elements of African culture and contemporary life. One, for example, shows a Black man dressed in an African kufi hat, with an eye patch featuring an Egyptian design. His other eye glows with light, and he points to his temple, as if he is enlightened to some sort of truth. It reads: “Y’all working for Quicken Loans, but not QUICK to LOAN a brother a hand in the fight against oppression.”

Read more from the archives: “Do Black Lives Matter in Outer Space?”

The line between genuine Hotep posts and posts intended to poke fun at the Hotep subculture has become blurred. For example, one shows a Black man dressed as an Egyptian pharaoh with the caption: “After you’ve defeated all the Hoteps, this is the final boss. Becarful (sic), he will connect 9/11 to the Atlantic slave trade in one sentence.” This meme is clearly a satire of the conspiracy theories sometimes attributed to Hoteps, such as that the lab mice used in medical research are “albino” and therefore not suited to developing medicine for people of color.

An obsession with Egypt is not new; extensive cultural fascination with Egypt goes back to the late 1700s, when Napoleon Bonaparte’s campaign to North Africa inspired interest in Egyptian art and archaeological remains. Museum exhibitions starring King Tutankhamun in the 1970s kicked off a new spate of “Egyptomania” in the Western world: The 1972 show of Treasures of Tutankhamun at the British Museum was the first ever blockbuster exhibition, drawing hundreds of thousands of visitors. Ancient Egyptian art has become both familiar and exotic in mainstream culture.

For a young Black person struggling to connect to their ancestral cultural heritage, ancient Egypt is a familiar, attractive place to start. Egypt is the most well-known and powerful cultural influence from Africa today, making it easy for many African Americans to adopt Egyptian culture and to use its legacy of royalty, artistic sophistication, and technological advancement to create a message of Black superiority.

The trauma and loss of African heritage through the transatlantic slave trade arguably created a gulf that was filled by a kind of “therapeutic mythology”—a constructed heritage built around memories of the homeland. From Egypt to nations across the continent, the historic and renewed connection to Africa created the unique identity of “African American.” This identity encompasses a culture where African traditions (the ones that survived a long history of colonialism) have been altered to fit new, American environments.

For a young Black person struggling to connect to their ancestral cultural heritage, Egypt is a familiar, attractive place to start.

In the early 20th century, at a time when Blacks were very much politically, economically, and socially disenfranchised in the United States, Afrocentrists like Molefi Kete Asante and Black scholars like W.E.B. Du Bois highlighted a relationship between ancient Egypt and modern Black Americans in order to instill a sense of pride for Black achievement. However, these links contain the implicit, inaccurate assumptions that all ancient Egyptians would have physically resembled those who self-identify as Black today, and that all modern Black people can trace their lineage to ancient Egypt. Nevertheless, these ideas have trickled down into the mainstream: Many of my Black family members and friends have Egyptian-esque decorations in their homes to celebrate Black culture and pride.

Ironically, perhaps, recent research has shown that early Egyptians were mostly lighter-skinned: Genetically, Egyptians did not mix with darker-skinned sub-Saharan peoples until the last 1,500 years, well after the end of native Egyptian dynasties. I have seen the ancient word for the Nile Valley, Kmt—which translates as “black land”—used as evidence that Black people lived in Egypt; actually, it refers to the black, fertile soil of that region.

When viewed through an anthropological lens, I understand how the Hotep subculture fosters positive identity constructions. The Hoteps movement is a testament to the uniquely painful and complicated history of African Americans. It is anchored in a long tradition of looking to Africa for points of needed pride. Yet it also risks propagating false histories and conventions, and, ironically, disparaging Black women and those who are LGBTQ in the service of elevating Black identity.

There are plenty of positive examples of contemporary Afrocentrism: African culture has become influential in American media in the last few years, such as in the Afrofuturist movie Black Panther, the rise of Afrobeats in American music, or even Beyoncé’s increasing use of Egyptian aesthetics in her clothing line. I do not see the self-identification of African heritage by the Hotep subculture as problematic: The re-creation of a lost African heritage can often be therapeutic for the Black community.

What should be examined more deeply is the way the Hotep narrative could be damaging. Hotep memes, and the history and logic that underpin this subculture, reveal the ways that the movement depends far too often on misogyny, homophobia, inaccurate history, and stereotypes of the Black experience. A serious reflection on how modern subcultures create their identity is critical to ensuring that the same violence that created African American identities is not perpetuated in the future.