What Rez Dogs Mean to the Lakota

A tragic event occurred on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, South Dakota, where we live, a few years ago: the death of an 8-year-old girl. She was viciously attacked and killed by a pack of dogs while sledding a few steps away from her home. In response, Lakota tribal officials rounded up stray dogs from the communities and killed them.

Sadly, a similar incident took place in 2015 on the neighboring Rosebud Sioux Indian Reservation, where a 49-year-old woman was also attacked and killed by a pack of dogs. Again, stray dogs were picked up and taken away to be put down.

Google searches pull up plenty of U.S. headlines of dog attacks, often recorded in tribal media and community newspapers: “Pit bull attacks young boy”; “Dog attacks 84-year-old woman”—headline after headline. Pit bulls often monopolize the negative press, but they aren’t necessarily the issue for us on the Pine Ridge Reservation. It doesn’t seem to be a particular breed (or hybrid mix) that is the issue but more the phenomenon of the animals organizing into packs.

Tragedies of many kinds are often all too common for many people who reside on our reservation. Endemic poverty creates endless problems for community members, from violent dog packs to pervasive alcoholism and diabetes. Dismal statistics paint our reservation as the “Third World” right here in the United States. The numbers are hard to pin down but always dreary: Unemployment is sometimes listed as being as high as 85–95 percent, and more than 90 percent of the population lives below the federal poverty line. In this environment, caring for dogs or other animals is often simply at the bottom of the priority list.

But this story isn’t intended to be one of the ever-present poverty narratives you’ve likely come across, the kind that often gets deemed “poverty porn” for entertaining the base instincts of a more privileged audience.

Instead, this is a story about the longstanding, deep cultural meaning that dogs have had for Lakota people, and the tragic downfall of dogs in our society. As Lakota tribal members with a background in anthropology, we can see that this history is often misunderstood or ignored.

In our culture, people traditionally don’t own animals the way other cultures have pets; the animals are left wild, and may choose to go to a home to offer protection, companionship, or even to become a part of a community. People feed the dogs and care for them, but the dogs remain living outside and are free to be their own beings. This relationship differs from one where the human is the master or owner of an animal who is considered property. Instead, the dog and people provide service to one another in a mutual relationship of reciprocity and respect.

But something has clearly gone wrong with this system; things are out of balance. How did we, as a tribal people, come to this point—a place where our community members are being killed by our fellow “relative,” the dog, and where the dogs are now seen as “beasts” and have to be killed for our protection?

Dogs, just like American Indians, had a long and complex history prior to the intrusion of Wasicu (White settlers, or, literally, one who takes the fat) and so-called modernity in North America. Dogs were an integral part of Plains Indian history. [1] [1] Lakota is a spoken language with a variety of orthographies in different communities. The translations in this article rely in part on the authors’ own interpretations.

In the Lakota language, there is no hierarchy of animals. All animals, including people, horses, dogs, and so on, belong to oyate (a group of animals/organisms). None of these oyate hold dominion over others, and they share existence on the planet within nature. The notion of humans being at the top of the chain, superior to other animals, is a colonial one.

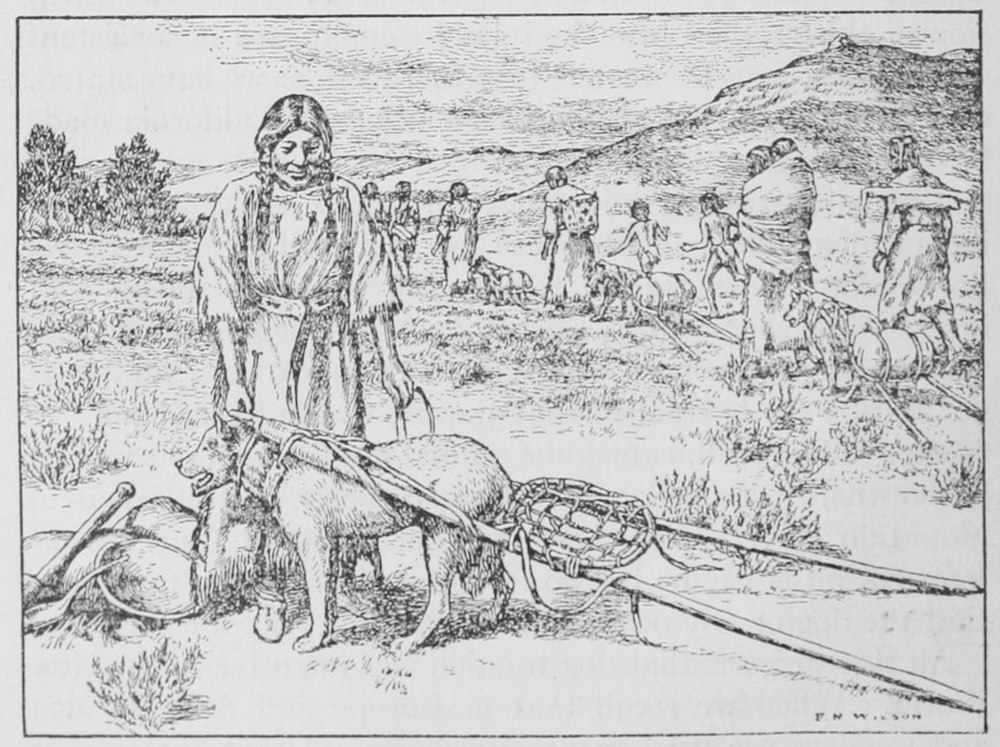

Historically, in the Lakota culture, a dog (sunka, pronounced sh-UN’-ka) was seen as a sacred being that protects the camps and provides various sacred rites. The dog also helped people, prior to the horse, by carrying wood, keeping watch of the camp, or towing the tipi in what is known as a travois. The ideas of the dog and its spiritual connections are complicated and often particular to different healers in the communities.

Lakota have been noted to sometimes eat dog, or more specifically, puppy. “It gave itself to us as medicine, that’s why we have kettle dances,” says one of Ernest’s unci (grandmothers). Much like the concept of kosher in Jewish culture, food in Lakota culture requires ceremony to keep a proper balance within the natural world. There is a healing property associated with eating puppy. All food is “medicine” to some degree and serves a purpose that is often intertwined with a story.

There is a story in Lakota culture about an old lady and a sunkpala (puppy) that we all are told growing up. The old lady is quilling—a craft that uses porcupine quills to adorn various items—a buffalo hide, and it is said that when she finishes the hide, the world will come to an end. Luckily, the sunkpala is there to help because, as the story goes, when the lady gets up to tend to something else, the puppy undoes some of her work, thus giving people a little more time on this planet. This story is documented and popular, and it is not one of the many that remain held in private possession by the different tiyóšpaye (extended families).

Elders who speak our language know that there are more stories that have deeper meanings. It is said that the dogs understand the Lakota language and that the many stories out there are meant to be spoken and intertwined with specific contexts by specific families.

The stories embodying traditional cultural knowledge—about dogs and so much more—have been eroded by modern life, including modern-day struggles of alcoholism, drug use, health disparities, and loss of language.

Historians often write that when Wasicu and horses reached the plains in the 1700s, dogs lost their place in our societies. In the Lakota language, the word for dog—sunka—was used and altered to describe horses—sunka wakan—as another type of sacred dog. Though the dog may have become overshadowed by the horse, it was still an invaluable relative.

Today rez dogs roam tribal communities looking for food and shelter. Some of these rez dogs are cared for and have a place to call home. They are not seen as “pets” in the middle-class American sense, but that does not mean people don’t show them respect or fond feeling.

Others, however, are neglected, creating a situation where dogs starve and become violent. Richie has seen from his own window last winter a pack of dogs tearing apart another dog for food. The dogs, like the people, are often hungry and not afforded the comforts of an inside dog that falls within the category of a pet.

It takes a lot of resources to treat a pet like a child—resources that many people on reservations simply don’t have.

To an untrained eye, all these dogs may look lost or neglected. But some are just meandering along life’s journey. At a powwow, or wacipi (they are dancing), dogs walk around as people do, checking out the scene, visiting with relatives, and seeing what vendors have to offer; they seem to know not to go into the dancing arena out of respect.

Like the slang term “hood rat,” a derogatory phrase used to refer to adolescents in low-income areas, “rez dog” can also now refer to a younger person found within a tribal community who seems, to outsiders, to be walking through life without purpose. This highlights areas of misunderstanding or disagreement between the cultures.

Meanwhile, the place of dogs in mainstream American culture has also changed, where they’ve become more like family members who need and deserve pampering. In a 2011 online survey of 1,000 North Americans conducted by Kelton Research, 60 percent of participants said their dogs are, according to a Psychology Today article about the study, “currently more important in their lives than were the dogs that they had during their childhood days.” This shift has made the contrast between mainstream American pets and rez dogs even more stark.

It takes a lot of resources to treat a pet like a child—resources that many people on reservations simply don’t have. On the Pine Ridge Reservation, many of our fellow tribal members don’t have enough to feed their own children. Caring for a dog as a child is often economically impossible. Veterinarian services may be unavailable, even if people could afford to pay for such services.

Pine Ridge Reservation community members and volunteers from across South Dakota founded the Oglala Pet Project (OPP) in 2011 to rescue abandoned, unwanted, and abused animals, especially dogs. The OPP also works to provide medical services to reservation animals: Animal clinics usually come around once a year, offering vaccinations and spay/neutering services to the communities. The Oglala Sioux Tribe also enacted Braeden’s Law Oglala Sioux Tribal Council Ordinance No. 06-16, named after a boy who, sadly, was attacked by a pit bull in 2006, banning certain dog breeds from shared residential spaces.

Despite the help of the OPP, most reservations in South Dakota lack the funding to operate sufficient animal control measures, and accidents still happen (like the one on Pine Ridge in 2014). It takes a tragedy to remember the importance of such programs. When a child dies, something has to happen. On many reservations, the “something” is often people rounding the dogs up and killing them.

On the Pine Ridge Reservation, several other outside organizations have also recently sprung into action out of a desire to save people from attacks and dogs from euthanasia. There is something awkward, however, about outside groups swooping into the reservation to save dogs, extracting them from their native culture to live healthy, happy lives in mainstream America.

It is hard to say what the right solution is, or how to reinstate a balance between people and dogs on these reservations or between caring for the dogs and allowing them to remain free. These are complex issues with complex solutions.

It will take a community to solve this issue and to recognize that it is people, not dogs, who have become the real beasts who are ultimately responsible for things being out of balance. We all have responsibilities and roles to play in our communities. In Lakota, we call this being a good relative and member of your tiyóšpaye.

If dogs and people can be brought back into harmony across American Indian reservations, it will take a lot more effort than just “rescuing” or killing the dogs.