When It’s Not Safe to Sleep

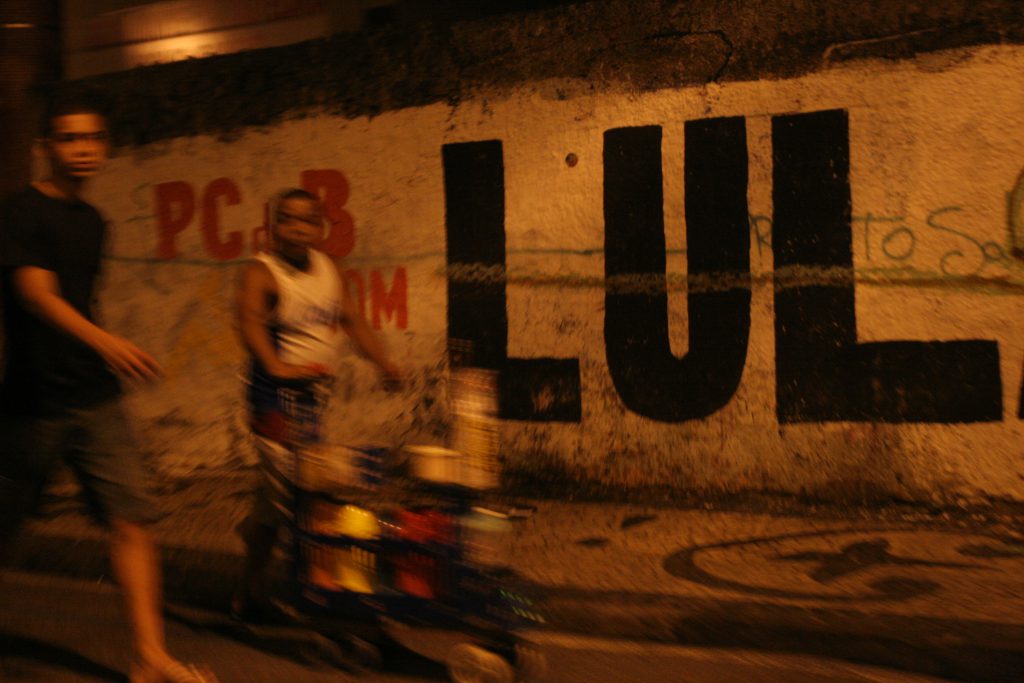

It is evening in Barra, a neighborhood and tourist destination in the city of Salvador, Brazil. It is April, autumn in the Southern Hemisphere, and there has been no sign of rain for days. Although the sun set hours ago, the air is still warm and humid. The streets in between chic high-rises are gradually emptying, with street vendors packing up and restaurants closing down.

Across from the police station, a small black-and-white TV is playing a classic Rambo movie. Taxi drivers wait nearby for customers, and boys in their early teens squat on the asphalt, watching the film. They have come from poorer neighborhoods to make a living by begging, doing odd jobs, selling drugs, and stealing in this more affluent part of the city. Among them is Lucas, a 16-year-old boy who has abandoned his father and stepmother’s household. He has lived periodically on the street for nearly a decade. [1] [1] All names in this piece (other than the author’s) are pseudonyms.

A couple of hours later, the boys have moved over to a staircase in front of a closed bar. Some are chatting, while others are huddling together to get some rest. Although many police have left on patrol, the police station operates day and night, which creates a sense of safety for the younger street dwellers. Lucas sits down on the end of the staircase. He feels an urge to lie down and rest, but he is chased away by one of the other boys. Lucas had been accused of having squealed to the police about who committed an assault a couple of days earlier, and now he has a “price on his head.” One of the older street boys threatened to light him on fire in his sleep. No one wants to sleep next to him.

Lucas wanders off and sits down on a fence along the beach promenade. The streets are almost deserted, with the exception of prostitutes and drug dealers. A street vendor passes, pushing a miniature trailer filled with thermoses. Afraid of drowsing, Lucas buys his 11th cup of coffee. He feels the caffeine making him restless but does not want to walk too far away from the police station. He has to stay awake, alert, and safe.

I first met Lucas in 2002, years before starting my career as an anthropologist. During the three months I spent in Barra while taking a break from my studies in Norway to travel abroad, I noticed a boy, then in his early teens, minding cars outside my building. One day we exchanged a greeting, the next day we had a short conversation, and then eventually we took walks together in the neighborhood. Three years later, Lucas became one of my key informants in my first ethnographic fieldwork as a master’s student in anthropology. A decade and a Ph.D. later, I was still following Lucas and his street peers as they navigated their way into adulthood. [2] [2] This article in part draws from the author’s new study in the Journal of Anthropological Research.

The opening story above was taken from notes I kept during my first year of fieldwork in 2005. When I started to accompany Lucas and the others living on the streets of Barra, I simply wanted to document what life was like for them. I quickly realized I would have to stay up through the night, as much of their social life and activity (some of it criminal) took place after the sun went down. I did not intend to study their sleep. But I was interested in the practicalities of street life and whether they felt safe or in danger—and sleep was a huge part of that. Throughout the years, I came to realize that patterns of sleep also changed as my informants matured.

People with a secure home often take for granted having a place where they can sleep soundly and safely. The surrounding middle-class residents of Barra lie down comfortably in dark, controlled, quiet, and secluded environments to rest through the night. For those living on the street, sleep is a very different experience.

The sleep that homeless kids get on the street—“sleeping rough”—tends to be fitful since they are under the constant threat of possible attacks, abductions, and homicides. Some sleep in packs or in public for safety; others seek out privacy and solitude. Some can only sleep in darkness, but others depend on sunrise to be able to rest. Sleep, for them, requires conscious and continuous calculations and strategizing.

Anthropologists have largely neglected sleep, focusing on waking hours for their studies. Over the past decade or so this has started to change, with studies looking at how people tend to experience sleep in different cultures: whether they nap, for example, or how many hours they sleep at night. For the homeless, though, sleep—or the lack of sleep—reveals something deeper.

Hours after midnight, Lucas feels dreadful, he tells me when I meet up with him at the beach promenade. He watches the nocturnal street life, trying to stay on guard in case the boy who has threatened him appears. Some of the older boys shuttle between the promenade, where they sell drugs to people in passing cars, and the shoreline rocks, where they smoke crack cocaine. Three of them appear with newly conquered cell phones and wallets. They brag about mugging a tourist couple, before taking a taxi to sell their goods downtown.

Eventually Lucas walks toward the inner and more secluded parts of the neighborhood, searching for a hidden place to rest. He lies down in between a parked car and a residential house, but he can’t relax. Filled with paranoia, he pays attention to every sound—from footsteps to motors. Is it close? Is it moving in his direction? Even though his hiding place is secluded, that also means there are no witnesses around in case someone attacks. Lucas finally decides that it is not worth the risk. He gets up and returns to the square close to the police station, buying yet another coffee while waiting in agony for the day to start.

At sunrise, people pour out into the streets again. Some are headed for a swim at the beach, others are rushing to school or work. Amid the commotion, Lucas feels seen and safe. He knows it is risky for others to attack him when he’s asleep and there are people around. Outside a restaurant that opens in the afternoon, he lies down, covers his head with his T-shirt, and finally falls asleep.

Although the details were different, many of my informants during my early years of research described similar scenes to those I witnessed and analogous stories to the ones Lucas shared with me. Their experiences highlighted some of the ironies about sleep and survival on the street. Each thing the young men do in search of safety comes with its own risks. They sleep in packs, but members of that pack might attack another person in the group. They try to hide, but then there are no witnesses if something happens to them. Some smoke crack to stay awake through the night, but the drug makes them paranoid—and the cravings make it more likely that they will join a life of crime, which would give them other reasons to be afraid.

One of the older street boys threatened to light him on fire in his sleep.

Lucas was younger and less involved with crime and drugs. Others who I worked with were different; they were more adapted to the streets. When I returned to the field three years later, in 2008, I met Maicon, who was 20 years old at the time. Like Lucas, he had avoided both heavy drugs and petty theft during my previous fieldwork seasons. But by 2008, Maicon’s life had changed dramatically. He explained that he had started to smoke crack to avoid getting “fucked over” by street peers at night. He would burn the midnight oil, finding ways of earning money—drug dealing, theft, assault, burglary—to support his drug habit. His strategy, like Lucas’, was to eventually fall asleep amid passersby after daybreak.

Another young man I met at that time, Caio, who was in his mid-20s, only faintly remembered the times when he would sleep huddled together with peers in the public gaze. As the years went by, he gained a bad reputation in the neighborhood and lived in constant fear of retaliations. His favorite sleeping spot was in a particular home’s backyard. He carefully kept it secret, always going there alone and taking detours to prevent anyone from following him.

Christian, who was approaching age 30, was among the oldest in the street environment in 2008. He had retired from heavy street crime, and he used to sleep at the rocks near the shore—in the open air and visible. “I feel more secure when I feel that I’m being observed, when I feel I’m being seen,” he told me. Yet his trust in his surroundings was not complete: He often slept with his hand on a harpoon and with his ear glued to the rocks to listen for footsteps. Vito, another of the more seasoned street dwellers, kept two trained dogs to watch over him.

During my most recent season of fieldwork in 2016, Lucas was living with his stepmother and siblings in a poorer suburban part of town. He only went to Barra occasionally—and only during the daytime. Christian was staying with his cousin downtown, while Maicon continued dealing drugs in Barra. No one seemed to know about Vito’s whereabouts. When I last met Caio, he had moved into a shack with his girlfriend in a slum not far from Barra. At the time, he explained that the streets were not safe for him anymore. Ironically, and tragically, he survived the streets but was killed in his home just months after I visited him.

Following their stories on and off the streets, I came to learn that sleep—or the lack thereof—played a bigger role in these young men’s lives than most of us could imagine. Those of us who are able generally spend one-third of our lives asleep. Our intimate, confined, and comfortable sleeping arrangements make us think little about sleep, and we talk even less about it. When having a secure, reliable place to sleep is not a given, the essential role of sleep in our lives becomes much more evident. Only then can one see that sleep is about survival. Shifting out of a vigilant, defensive state to slip into one’s unconscious requires safety, which is hard to find out on the street.

Sleep is a universal human need, which is why it can act as a common bond for all of us, reminding us of our own vulnerability and shared humanity. My hope is that by learning about their experiences with sleep, we can identify with street dwellers on an elemental human level, ultimately dissolving boundaries between “us” and “them.”