Hunting Down the Facts About Paleo Diets

This article was originally published at Knowable Magazine and has been republished with Creative Commons.

What did people eat for dinner tens of thousands of years ago? Many advocates of the so-called paleo diet will tell you that our ancestors’ plates were heavy on meat and low on carbohydrates—and that, as a result, we have evolved to thrive on this type of nutritional regimen.

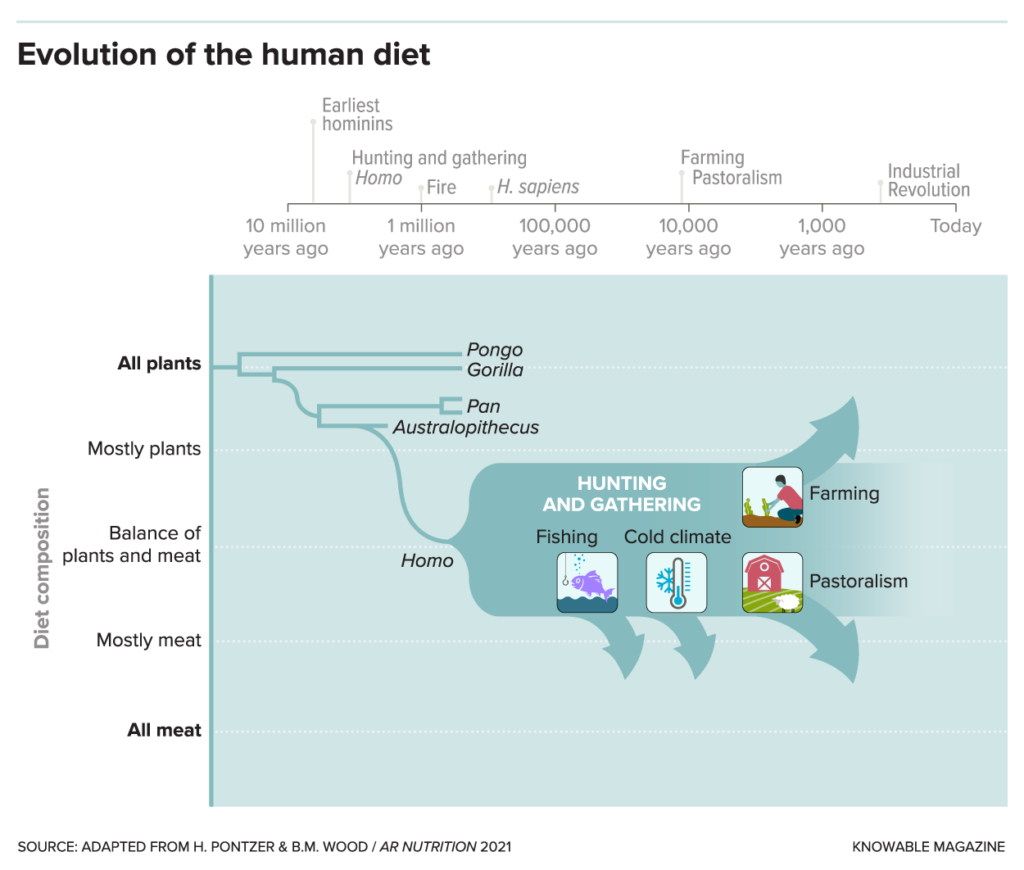

The diet is named after the Paleolithic era, a period dating from about 2.5 million to 10,000 years ago when early humans were hunting and gathering, rather than farming. Herman Pontzer, an evolutionary anthropologist at Duke University and the author of Burn, a book about the science of metabolism, says it’s a myth that everyone of this time subsisted on meat-heavy diets. Studies show that rather than a single diet, ancient people’s eating habits were remarkably variable and were influenced by a number of factors, such as climate, location, and season.

In the 2021 Annual Review of Nutrition, Pontzer and his colleague Brian Wood, of the University of California, Los Angeles, describe what we can learn about the eating habits of our ancestors by studying modern hunter-gatherer populations like the Hadza in northern Tanzania and the Aché in Paraguay. In an interview with Knowable Magazine, Pontzer explains what makes the Hadza’s surprisingly seasonal, diverse diets so different from popular notions of ancient meals.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What do today’s “paleo diets” look like? How well do they capture our ancestors’ eating habits?

People have developed many different versions, but the original paleo diet is quite meat heavy. I would say the same is true of the predominant paleo diets today—most are very meat heavy and low carb, downplaying things like starchy vegetables and fruits that would only have been seasonally available before agriculture. There’s also an even more extreme camp within that, which says that humans used to be almost entirely meat-eating carnivores.

But our ancestors’ diets were really variable. We evolved as hunter-gatherers, so you’re hunting and gathering whatever foods are around in your local environment. Humans are strategic about what foods they go after, but they can target only the foods that are there. So there was a lot of variation in what hunter-gathers ate depending on location and time of year.

The other thing is that, partly due to that variability, but also partly due just to people’s preferences, there’s a lot of carbohydrate in most hunter-gatherer diets. Honey was probably important throughout ancient times. A lot of these small-scale societies are also eating root vegetables like tubers, and those are very starch and carb heavy. So the idea that ancient diets would be low carbohydrate just doesn’t fit with any of the available evidence.

So how did “paleo” come to represent meat-heavy and low-carb eating?

I think there are a couple of reasons for that. You have a kind of romanticizing of what hunting and gathering was like. There is a sort of “macho caveman” view of the past that permeates a lot of what I read when I look at paleo diet websites.

There are also inherent biases in a lot of the available archaeological and ethnographic data. In the early 1900s, and even before, a lot of the ethnographic reports were written by men who focused on men’s work. We know that traditionally that’s going to focus more on hunting than on gathering because of the way a lot of these small-scale societies divide their work: Men hunt, and women gather.

On top of that, the available ethnographic data is heavily skewed toward very northern cultures, such as Arctic cultures—since the warm-weather cultures were the first ones to get pushed out by farmers—and they do tend to eat more meat. But our ancestors’ diets were variable. Populations that lived near the ocean and moving rivers ate a lot of fish and seafood. Populations that lived in forested areas or in places rich in vegetation focused on eating plants.

There is also a bias toward hunting in the archaeological record. Stone tools and cut-marked bones—evidence of hunting—preserve very well. Wooden sticks and plant remains don’t.

Your research has focused a lot on a group called the Hadza. Who are the Hadza, and what has studying their diets taught us to date?

The Hadza are a community of a few hundred traditional hunter-gatherers in northern Tanzania. They live in a sort of semi-arid savanna landscape. Some of the population has started to do some farming or to live in villages. But a quarter of them are still hunting and gathering, and get all their food from wild game and plants. Men hunt with bow and arrow, and women gather plant foods by hand or with digging sticks. They are this really wonderful community of folks to work with, but they’re also really valuable in terms of giving researchers a snapshot of what hunting and gathering really looks like, day to day, in real life.

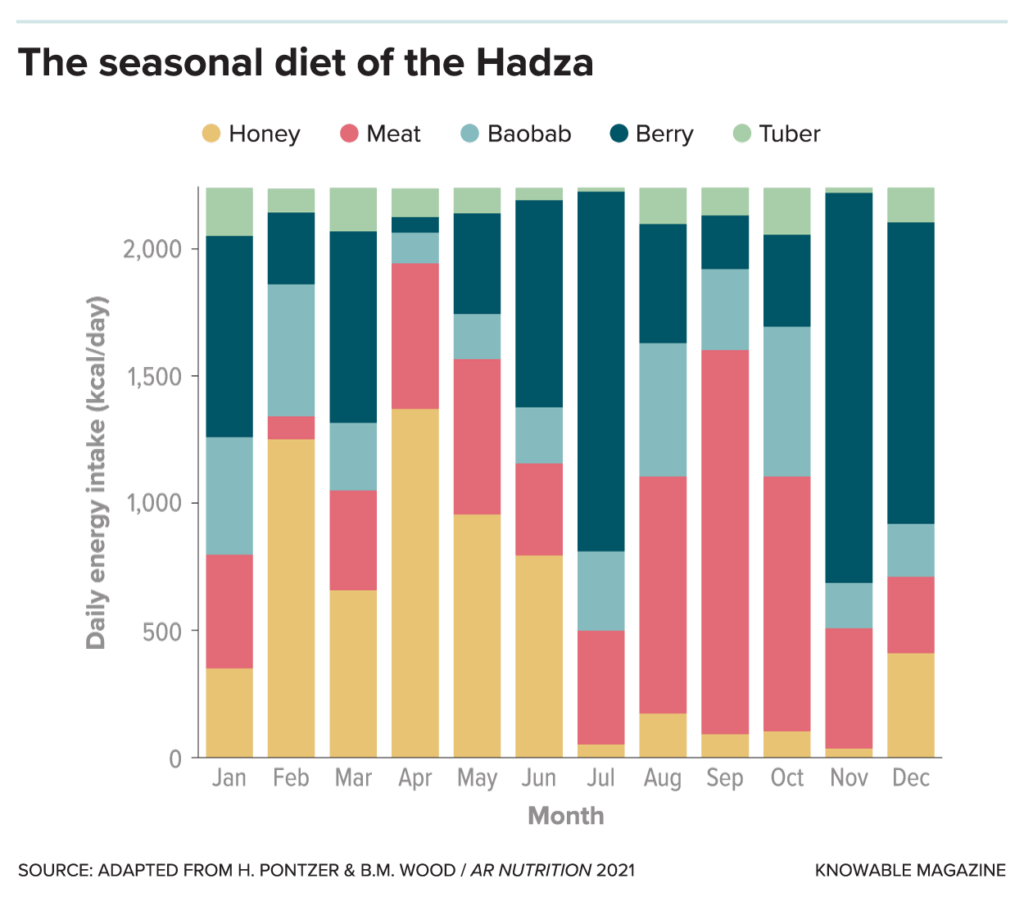

People have been working with the Hadza for decades now, so we have these long-term records, papers published from 30 or 40 years ago up through to today. We can understand from those data how variable diet can be: We’ve seen how the amount of meat changes with the seasons. It’s more skewed toward plants during wet seasons, for example. We’ve seen how different plant species, such as berries and tubers, contribute to diet in different ways over the course of a year. We’ve also learned that honey is a really big part of their diet.

What does the overall picture of their diet look like?

It’s a balance between calories from animals and calories from plants. The long-term average is around 50:50, but it varies. Sometimes they’re eating a lot of meat, sometimes very little. The one surprising thing from working with the Hadza—and it’s not just the Hadza, but a lot of the work with them kind of sparked this—is how important honey is. It can make up as much as a fifth of the group’s calories, on average. Honey is just sugar and water—pretty high carb and definitely not part of most modern paleo diets.

Why do the Hadza eat so much honey?

It tastes really good, and it’s packed full of calories. So they seek it out, just like we seek out good-tasting food in our environments. And in a lot of these habitats, it’s available year-round in big quantities.

Some of the Hadza make use of a bird called the honeyguide bird, whose entire foraging niche is dependent on honey-gathering by humans. I’ve had a chance to go out with the Hadza men while they were working with these honeyguide birds. It almost seems like the men are absentmindedly whistling while they’re walking, but they’re not. They’re doing this to attract the honeyguide bird. When they hear one of these birds, which make a kind of whirring, chirping sound, the Hadza men just walk directly toward the sound—and the bird will be calling and making a big fuss in the tree where the bees are.

The Hadza guys will look at this tree and confirm that there’s actually honey. Then they chop into the tree limb with their hatchets to get to the hive. Honeyguide birds are good at not just pointing to beehives—they’re good at pointing to big ones. So the Hadza get more honey when they are able to use a honeyguide bird. Of course, as they’re chopping into the tree and bringing out big chunks of hive, lots of pieces of comb and larvae get exposed and become the honeyguide bird’s meal. It’s a win-win situation.

The birds have adapted to a world in which humans get a lot of honey. I think that’s really telling.

How can you be sure that the way that people hunt and gather today looks the same as thousands of years ago? Maybe historically, hunter-gatherers used to eat more meat.

Recently, there’s been some really cool work looking at the little bit of plaque and calculus stuck to the teeth in fossilized hominids. If you look at that, you’ll find remains of plants and starches. So, we actually do have preserved evidence that early humans ate lots of starchy vegetable foods. There’s even some evidence of a primitive flourlike substance that’s made out of grains. That kind of thing is anathema to most paleo diets, which say that you can’t eat grains because grains are a farmed food.

And you can look at the human body and see how we’ve adapted relative to our ape relatives—what’s changed in us in terms of how we digest food. You can look at things like gut anatomy and tooth shape. And if you look at that, again, the signal is kind of omnivorous. It isn’t particularly meat heavy.

What can communities like the Hadza teach non–hunter-gatherers about what we should—or shouldn’t—be eating?

I think this adds to the evidence that humans can be healthy on a wide range of diets. I hope it helps tamp down some of the yelling on both sides about how you have to have a plant-based diet or you have to have a meat-based diet, or you have to have another kind of diet. These are really narrow views about what a human is built to consume.

Humans evolved to be adaptable. We are very much dependent on learning and developing these complex hoarding strategies to survive. And different people follow different paths. I think this adaptability is part of this whole package of how we live as a species. We’re built to be flexible. And flexibility means diversity.

That’s why people who follow these “paleo diets” that aren’t really paleo can often be really healthy. And people who are vegan, and eat no meat at all, can do really well too.

I think the one thing that they never have in a hunter-gatherer diet is the heavily processed foods that we are surrounded with. In processed foods, you get these combinations of sugars, salts, and fats that never occur in nature. You take out a lot of things like fiber and protein that make you feel full and put in a lot of things that make your brain’s reward systems light up, like flavoring. Processed foods seem to be a big driver of obesity.

So, maybe the one thing we can all agree on is to avoid that junk. But beyond that, eat whatever kind of diet that works for you and keeps you healthy.