Sexism Still Winning at the Olympic Games

I loved the Olympics growing up, and to this day, I remember iconic moments such as Kerri Strug’s one-footed landing in a 1996 vault and Michael Johnson becoming the first man to win gold in the 200-meter and 400-meter sprints in the same Olympic Games.

For me, the Olympics were an opportunity to see different parts of the world presented with a sort of reverent fanfare. An opportunity for activism. An opportunity for positive patriotism. An opportunity for whole countries to rally behind their athletes. And an opportunity to see those athletes perform record-breaking feats of strength and speed that defy belief.

I still love the Olympics and believe they continue to present these opportunities. However, as I have gotten older and read more broadly, the Olympics have lost some of their shine.

Any number of articles could be (and have been) written on controversies revolving around performance-enhancing drugs, racial injustice, the arbitrariness of some judge-based scoring, geopolitical tensions, and, of course, the devastating revelation of sexual abuse in gymnastics.

For me, sexism is a glaring issue.

This year, New Zealand weightlifter Laurel Hubbard became the first openly trans athlete to be picked for an Olympic team, which could be seen as a win for equality. But the rules regarding Olympic transgender athletes’ participation will likely be revised after this year’s event. With huge controversy swirling around the issue, it is unclear how inclusive those rules will be.

Olympic inclusivity—particularly with regard to women—has a storied past and present.

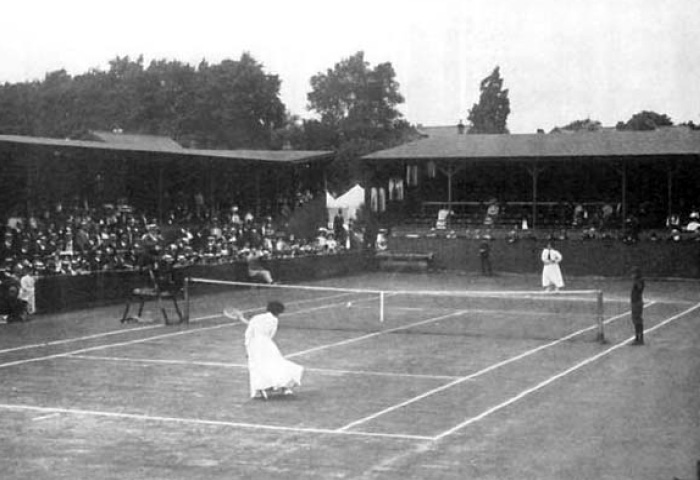

The official Olympic Games were founded in 1896, and like so many sporting competitions, they featured only male athletes. Though it only took four years for women to take the Olympic stage, they were relegated to a few select sports such as tennis, croquet, and figure skating. Perhaps this was partly due to beliefs that if women overexerted themselves, they could damage their reproductive abilities, as was put forth by Donald Walker in his 1836 book Exercises for Ladies. (It was also suggested that riding a train going 50 mph could cause a woman’s uterus to fly out.)

This arcane concern for women’s apparently delicate reproductive system is still, shockingly, present in modern times. Gian Franco Kasper, then-president of the International Ski Federation, in 2005 expressed concern for women participating in ski jumping—a sport that didn’t have a women’s category in the Olympics until 2014. So much jumping and landing, he said, “seems not to be appropriate for ladies from a medical point of view.”

Besides inclusion, another major issue has been the imposition of subjective ideals of femininity in both unwritten customs and written rules.

Take, for example, some athletic outfits: The traditional women’s beach volleyball uniform was a bikini (until 2012, they had no choice in the matter), while the men wore loose-fitting tank tops and shorts. This difference seemed to have roots in nothing other than the sexualization of the female form.

Similarly, full-body suits have long been more common for men than women in gymnastics: Some German competitors at the European Artistic Gymnastics Championships this year garnered press for pushing back on that.

The rules for eligibility, particularly for women, are also rife with sexist assumptions and issues.

The International Olympic Committee follows regulations put in place by World Athletics (more commonly known by its pre-2019 name IAAF, the International Association of Athletics Federations) to determine the eligibility of athletes in the women’s category of certain sports. These regulations are based on the idea that women with high natural levels of testosterone (a condition called hyperandrogenism) have an advantage, putting them at a competitive level similar to men.

This not only implies that men are inherently better athletes than women (they aren’t), but also that testosterone is the sole key to athletic success (it isn’t). Furthermore, naturally high testosterone levels are much lower than the levels present in people who have taken performance-enhancing drugs. Those looking for a meaningful performance boost from testosterone inject amounts several times what the body can make—a supraphysiological level.

The IAAF regulations have been challenged and modified after complaints. But, I’d argue, they are still problematic.

In the 2014 Commonwealth Games, Dutee Chand, who is from India and runs the 100-meter event, was deemed ineligible to compete in the women’s category due to her naturally high testosterone levels. At the time, the IAAF implemented an upper limit on testosterone levels among women of 10 nanomoles per liter—a level they contended would confer a 10–12 percent advantage. Chand challenged this ruling at the Court of Arbitration for Sport, which ruled that testosterone levels do impact athletic performance but that the IAAF could not support its claim of a 10–12 percent advantage. The IAAF had to suspend their hyperandrogenism regulation for two years and then submit evidence for new regulations.

The science behind this regulation is debatable.

In 2018, the IAAF shifted their regulatory focus to athletes who are intersex or have differences in sex development (such as women who have XY or XXY chromosomes). These new regulations determined that only such people, and only those participating in middle-distance running events of 400 meters to 1 mile, needed to artificially reduce their testosterone levels below 5 nanomoles per liter to compete in the women’s category. (Trans women must meet this criterion to compete in the women’s category of any Olympic sport.)

The science behind this new regulation, too, is debatable. Critics have pointed out that only three of the 11 running events analyzed by the IAAF showed a significant relationship between performance and testosterone. Meanwhile, other sports that did show a significant relationship between testosterone and performance (like the hammer throw and pole vault) aren’t covered by the regulation.

It’s worth noting that there is no similar regulation of men’s events: no upper ceiling of natural testosterone determining a man’s eligibility to compete; no lower level below which they might be eligible for the women’s category; and no limit on their natural estrogen level, which could confer an advantage in some endurance sports.

Whether the new regulation survives scrutiny of the supporting science or not, it still has the problem of treating intersex individuals as though they have a harmful disorder that needs correcting. The proposed solution of reducing testosterone levels can have multiple negative physiological side effects; some athletes have even undergone invasive surgery.

The new rules affect, for one, Caster Semenya, a middle-distance runner from South Africa who has naturally high testosterone levels and may be an intersex individual (such details are understandably not public). Semenya won the gold in the 800-meter event during the 2016 Olympics. When the new IAAF regulations were put in place, Semenya was not (and is still not) allowed to compete on the international stage in that event unless she reduces her natural testosterone levels. Semenya has repeatedly challenged these regulations, but to no avail.

In general, these rules have had a disproportionate impact on women from the Global South. This could be in part because running—the sport targeted by these regulations—has a strong sporting tradition in some of these countries. It could also be because of a long cultural history of women of color (not just athletes) having their femininity questioned.

Most, if not all, of the IAAF investigations that have made it into the media have involved women from the Global South. Just recently, two female runners from Namibia were disqualified from running in the Olympic 400-meter event for having naturally high testosterone levels.

The regulatory focus on testosterone seems odd when you consider that there are plenty of other ways in which people have biological advantages over others, many of which aren’t considered problematic or unfair.

Take, for example, Michael Phelps, a swimmer who has exceptionally long arms and double jointed elbows, and apparently produces half the lactic acid (high lactic acid levels contribute to fatigue) of other athletes. His natural biological variation is celebrated rather than regulated, while Semenya’s is vilified—despite the fact that Phelps has won 23 Olympic gold medals, while Semenya has won only one.

The reality is that athletic performance is determined by a wide range of features, including but not limited to the complex (and not fully understood) interaction between genetics, various hormone levels, mentality, training, nutrition, recovery, and even just how the athlete feels the morning of an event. Artificially assigning one characteristic as the defining feature of athleticism oversimplifies a complex issue.

If the aim is to level the playing field and avoid unfair advantages, there should theoretically be a host of different Olympic categories not just divided by sex but also by percentage of certain muscle fibers, or by length of leg, or by genetics … I could go on.

If this sounds ridiculous, remember that the Paralympics has multiple classes of impairment in an attempt to create equitable competition that merits “sporting excellence” alone. (It’s worth noting that not all “impairments” reduce sporting ability; some prostheses may be better than their biological equivalents.)

There is no perfect solution, but at least regulations could be put in place that are more grounded in science and more equitably applied. To do that, we will need more data on female athletes: This should provide a massive impetus for the support of more exercise physiology research done by women and on women.

Overall, the Olympic rules seem to ignore most natural variation and perpetuate outdated feminine ideals and an overemphasis on the powers of testosterone. This fuels stereotypes, misunderstandings, and discrimination.

There are signs of progress, but things don’t always move forward: Take, for example, the rash of anti-transgender legislation now sweeping across the United States. Over 20 percent of that legislation would make it illegal for transgender youth to participate in sports divisions matching their gender identity.

Those working to bar transgender individuals from participating in the gender category with which they identify, most especially transgender women, claim that testosterone, among other things, gives transgender women an unfair advantage over cisgender women. They worry, too, that men will falsely identify as (and possibly even transition to) transgender women and win in any and all sport contests.

The science doesn’t support the first claim. The second is patently absurd given the difficult, costly, and time-consuming process of gender-affirming procedures. Transgender athletes are not threatening the success of cisgender female athletes and are not dominating sports as legislators fear.

Scientists and sport-governing organizations need to actively push back against poor readings of science and outdated ideas about women’s bodies. I can think of no better stage for that than the Olympics.